Here at the CR, we like our editorial assistants to have extra skills (in addition to perceptive reading acumen, superior letter-opening talents, and a song-and-dance routine), so we were thrilled when Michael C. Peterson joined the staff. As we’ve blogged about before, Michael has welding experience. When we learned that, we asked him to grab his welding helmet and acetylene torch, to fix our conference table, which a volunteer-who-will-not-be-named had karate-chopped in a fit of rage at the lack of stories about laser cats. Michael grabbed his equipment and got started. Though we had to shield our eyes from the brightness of his flame, as he worked we heard him share the following appreciation of Peter Cooley’s poem “Possible Body,” from our upcoming Issue 9.2. (You may notice that the Bowie video he describes features a brief scene with welding and more, starting at 1:38.) After half an hour, he had repaired the unfortunate damage AND enlightened us:

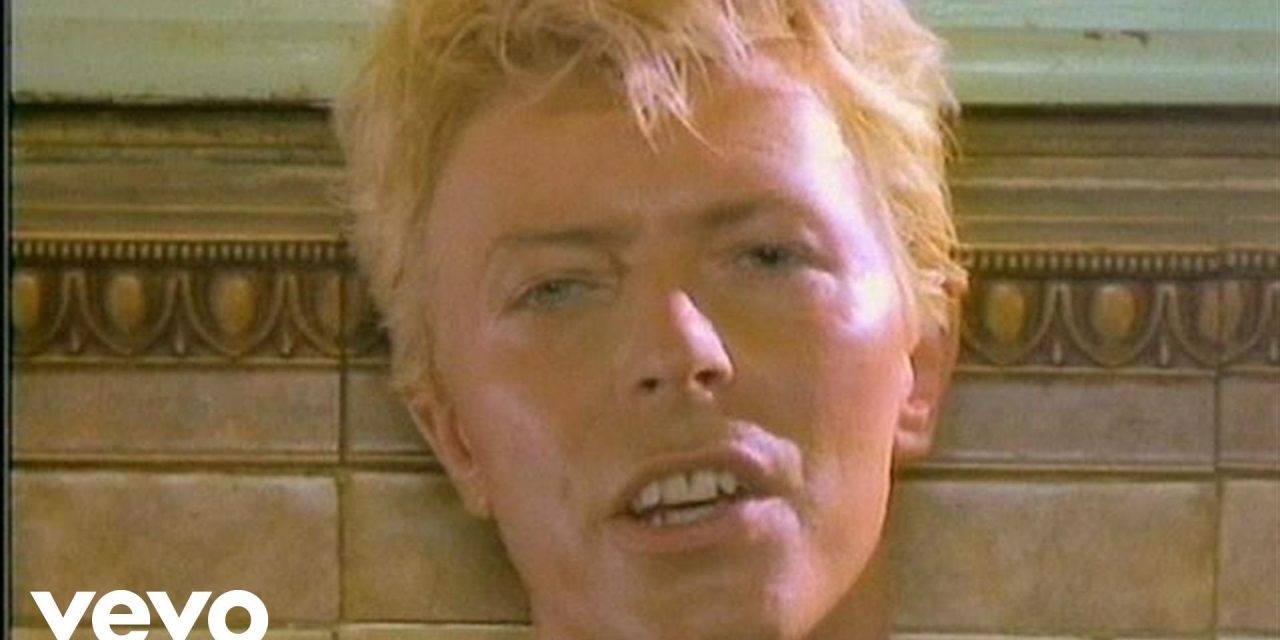

Michael C. Peterson: I’m trying to recall that fantastic/terrible David Bowie video. I think it’s “Let’s Dance.” You know, the one where Bowie is somewhere in the middle of the Australian outback, pretending to play the guitar just as well as the guy who actually played it on the track. Stevie Ray Vaughn, I think. There was all this wind, and Bowie’s trousers were really going nuts. Actually, it may have been Brazil, and there were these weird primitive-looking, shirtless teenage kids who were searching for this big modern city, and Bowie’s chiseled face was sort of palimpsesting over everything.

I might be making this up. I don’t think I am. I feel like I just saw it yesterday, but as if yesterday is right now. Which is how I feel reading Peter Cooley’s exceptional “Possible Body,” a poem that works brilliantly to answer a hypothetical by way of similar extension across time and space. I like Cooley’s piece for its elision, its sliding quality in both sense and sound. “I’m you, that’s why I understand your speech,” the self says. Not so fast. “Beggar come up below the overpass/ To ask me in—Vietnamese?—for cash,” the self says, recalibrating. These slips and recalibrations are the low-humming engine of “Possible Body” and, for me, the loci of its pleasure. Lines click over like synapses firing, the capacitors of the poem’s circuit releasing current; it is a kinetic by which a variety of personal histories might coincide. Cooley’s poem feels timeless not just for its across-time-ness, but because it seeks a transcendent moment of out-of-time-ness in which we might connect with future selves without total irreversible consequence. The effect is near perhaps to what the poet Robert Duncan calls “the psychic depth of time transformed into eternity”—a transport fundamental not just to the work of poetry but to the work of the self.

In any case, the point in all of this is that those kids in that Bowie video (either primitive or futuristic) were looking for a city (either Sydney or Brazilia) so they could dance on that dusty hill against some difficult futurity. It doesn’t matter which city, or what year. It is, rather, that the search is so fundamental. Cooley’s poem reminds us that it must both send us out and bring us home. In doing so, the dance becomes both revolutionary and timeless.

Order Issue 9.2, or any other issue, here.