Once a day or so, at least one of us here in the office will suddenly jerk awake, lift her head off her desk and—with a long string of drool still attached to a submitted manuscript—speak a line or two from a story or poem before clunking her head back to the desk again. Then the rest of us will carefully slide the manuscript out from under our sleeping coworker’s face, clean the story or poem of drool, and read it. Because we know that good literature haunts your dreams. It’s a perk of the job.

Once a day or so, at least one of us here in the office will suddenly jerk awake, lift her head off her desk and—with a long string of drool still attached to a submitted manuscript—speak a line or two from a story or poem before clunking her head back to the desk again. Then the rest of us will carefully slide the manuscript out from under our sleeping coworker’s face, clean the story or poem of drool, and read it. Because we know that good literature haunts your dreams. It’s a perk of the job.

However, we were perplexed when our friend Tessa sleepwalked to our office in the middle of the night during a winter storm, woke us up by throwing open the door and—the whole time gesticulating with a blow-dryer —shouted, “Feed us your softest child!” Then she tightened her robe, took all of our extension cords, and shuffled back out into the storm. In the morning, we looked out our window onto the white quad below and saw that the following message had been blow-dried into the fresh snow.

Tessa Mellas: A habitual multi-tasker, I started Alexander Lumans’s story “Before I Offer Myself to the Birdmen” while blow-drying my hair. When my hair was done, I was completely engrossed by its kick-ass premise, tight sparse prose, and mad creativity—and rather than bookmarking the story with toilet paper (my usual tactic), “Birdmen” followed me to the bedroom, where I huddled under the covers, finished the story, and slid into sleep thinking about hybrid human/bird creatures with bloodshot eyes flying into my garden, demanding, “Feed us your softest child,” then dropping my progeny onto the top of a battlement made of babies, designed to protect the birdmen flock in their birdmen swamp. I hear that fabulist horror is good for REM sleep.

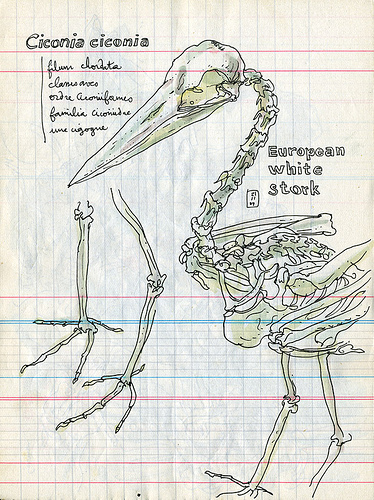

I woke up still wondering about the story, thinking about storks and the way they function as a euphemism for the horror of birth, thinking about how the stork is the adult version of Santa—a benign, generous creature that delivers exactly what humans most want, a magical entity that serves people—and how Lumans’s birdmen are the opposite of that.

I also thought about the millions of birds that break their heads on our windows, get covered in our gulf-spilled oil, and electrocute themselves on our wires. So then I thought, well, maybe people deserve for their babies to be taken away by birdmen. Look what we do to the birds. But then I remembered that the birdmen were part human, and that seemed to mean something else.

So I wondered why the birdmen built their wall out of babies. Why was this the ultimate defense? Was it a statement about innocence and experience? Power and helplessness? Avarice and value? And what about the townspeople’s behavior—handing over their children to the Birdman Defense Fund? Why nurture a baby only to give it up to die? The cogs and wheels in my head jammed up. The appropriate theoretical algorithm yielded no neat, tidy results. And as in all magical realism worth its weight in babies, this story was doing what it’s supposed to do—tossing out something strange in order to problematize our responses. I love this story for gumming up my insides and monopolizing my attention for a week. Well, maybe more than a week since I am thinking and writing about it still. And I imagine that all my life a wall made out of babies and the image of birdmen with children in their beaks will revisit me for a fun reunion. How many stories can say that?