Musings by José Angel Araguz

Episode 6: Meditation

In this episode I explore ways in which meditation can apply to the craft of poetry.

Some Preliminary Thoughts

Before getting into the nitty-gritty, however, it’s worth framing my own outlook on meditation as it has developed over the years. First off, meditation is simply being. While there are a great number of apps (I’m using Calm at the moment, but have also worked with Buddhify and Headspace) which provide guided meditations and/or music and soundscapes which add to the experience, what one essentially does in meditation is make the intention to set aside time to exist within their own mind.

Now, while meditation can be done sitting on the floor, in a comfortable chair, sitting cross-legged, it can also be done lying on the floor, on your bed, lying flat or with your knees up, etc. Meditation can also be done by walking, or even listening to music. I wake up every morning and read a few poems aloud; I don’t study or analyze them, I just let them ring out in the air. As can be seen, most activities can become meditative if approached with the intention to engage in them with full attention.

Though some religions do incorporate meditation into their rites, meditation is not a religion. It is not a diet, not a set of principles or a new way of life. There are many privileged, ableist, and potentially triggering materials out there that put pressure and misguided expectations on a practice that should be about not feeling pressure and expectations. Meditation, like poetry, is about setting the intention to go let yourself be in a room simply breathing (or writing down words). Approached this way, both poetry and meditation offer answers to the question of: How does it feel to exist?

Learning from the Pine

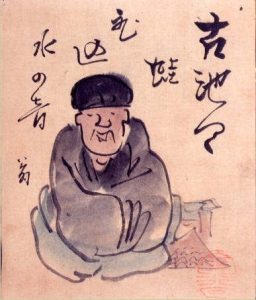

One of the first poets that came to mind when I began to think about this subject is the classical Japanese poet Matsuo Basho. Famous for his haiku and travel journals, Basho was also a great teacher. One famous lesson begins with the suggestion to “Learn about the pines from the pine, and about bamboo from the bamboo.” He goes on to say:

One of the first poets that came to mind when I began to think about this subject is the classical Japanese poet Matsuo Basho. Famous for his haiku and travel journals, Basho was also a great teacher. One famous lesson begins with the suggestion to “Learn about the pines from the pine, and about bamboo from the bamboo.” He goes on to say:

One must first of all concentrate one’s thoughts on an object. Once the mind achieves a state of concentration and the space between oneself and the object had disappeared, the essential nature of the object can be perceived. Then express it immediately. If one ponders it, it will vanish from the mind.

This mix of concentration and expression in the face of moments “vanishing” connects to meditation in terms of how hard it is to exist. Meditation is often considered a calm, easy thing. Yet, as soon as you close your eyes, all you sense is chaos: you daydream; your to-do list and responsibilities come immediately to mind; or a past memory surfaces and distracts you. These distractions can happen even on a walking meditation, when you begin to worry and stop noticing the things you pass on your walk. When any of these happen, it is your attention span and energy that vanish. Meditation is engaging directly with this chaos inside, and, for at least five or ten minutes, letting it go.

The small victory of letting yourself take the time to write, to pull out the notebook or open a fresh document and let yourself begin the process of writing requires a similar mix of concentration and letting go. A poem begins with a few words—but which words? Sitting before a blank page can not only leave you stuck, it can also make whatever nerve you had to write vanish. Writing prompts are great tools for writing into a meditative space exactly because they give us a way to begin. With a set of words or a theme, the mind can focus on creating, following the sense of the words.

Revision Mind

That feeling of being stuck before a blank page not knowing where to start can, with meditation, over time be worked into what I like to call “revision mind.” When meditation forces us to exist in the space behind closed eyes or the space of noticing what is in front of us as we walk—noticing and letting it pass, not studying or analyzing—it places us in the same space as when we sit in front of words.

One thing I like to do when revising a poem is to rewrite it by hand. This act places me back into the same silence as when the first draft was written; it also allows me to consider each word again. One line at a time, the poem gets rewritten slowly, and the full range of emotions—from This is brilliant! to Whose idea was it to let me move around words???—is experienced. If I set the intention to not judge the lines and not get hung up on the inadequacies of the poem (which the ego, of course, sees as a reflection of my own inadequacies), I make room for possible changes as well as acceptance.

We return to our favorite poems by others because of what we find in them, and what we find is often simultaneously familiar and new. Our own poems work in the same manner, and yield possibilities beyond the first few drafts if approached with intention and consideration. It is too easy to seek the reassurance of brilliance or reflection of inadequacy in our own poems; however, a poem doesn’t need that validation, people do. And we owe it to our poems to treat them like poems, to “learn about the pines from the pine,” as someone more brilliant and more adequate than me put it.

We return to our favorite poems by others because of what we find in them, and what we find is often simultaneously familiar and new. Our own poems work in the same manner, and yield possibilities beyond the first few drafts if approached with intention and consideration. It is too easy to seek the reassurance of brilliance or reflection of inadequacy in our own poems; however, a poem doesn’t need that validation, people do. And we owe it to our poems to treat them like poems, to “learn about the pines from the pine,” as someone more brilliant and more adequate than me put it.

Attention

In her contribution to the book A God in the House: Poets Talk About Faith, poet Jane Hirshfield discusses her time in a Buddhist monastery, when she did “nothing but practice Zen.” She goes on to share:

When I returned to poetry…I brought with me two things I now can see would be useful to any young aspiring writer: the monastic model of non-distraction and silence, and the experience of calling oneself into complete attention. The ability to stay in the moment, to investigate immediate existence through my own body and mind, was what I most needed to learn at that point in my life, and to learn to stay within my own experience more fearlessly.

Because of the attention it asks us to pay to the shifts and nuances of how we feel while existing, meditation is a way to become fearless and be able to stay within your own experience. While my thoughts here only begin to explore the connections between meditation and poetry, if nothing else I hope I have established the value of attention in both activities. Attention, which in meditation talk is often termed mindfulness or awareness, is invaluable to poetry. By having us pay attention to words, poems open ways for us to pay attention to the world.

*

For more on Basho’s lesson, go here.

To read the full excerpt from A God in the House, go here.