Musings by José Angel Araguz

Episode 4: Astrology (Virgo)

In this second astrology-themed round of this column, I scrutinize my own sign via a tour of quotes from three Virgos of American Poetry: Charles Wright, Kay Ryan, and William Carlos Williams.

First Stop: Charles Wright

In my previous post, I spoke of Pisces poets as having in their work “a sense of being forgotten, dismissed, and misunderstood, as well as being generally okay with that. Kind of.” Virgo being the polar opposite of Pisces, I want to start this tour by connecting with this previous thought, amending it further for Virgo by saying that the work of poets under this sign is driven by a sense of not wanting to forget, to dismiss, or be misunderstood. I like to think of it in terms of being polite as well as wanting everyone included. In the Virgo poets I admire, this inclusion is done by focusing on indirect clarity and openness of form.

To get a better idea of what I mean by indirect clarity, here’s a quote from an interview with Charles Wright in response to his work being seen as shying away from “straight narrative”:

“It’s simple, really. I can’t tell a story. Only Southerner I know who can’t. And, in truth, I have no real interest in telling one. The point of telling a story is the telling; the story itself is not the point. I always wanted to get to the end and find out what the point was. Still do.”

I often think of this quote when I find myself in conversation, going off on tangent after tangent, unable to tell a story or anecdote in a linear fashion. While this may make for tedious conversation in real life (at least in my case), on the page it translates for Wright into an elastic lyric sensibility, as this excerpt from his poem “The Appalachian Book of the Dead” illustrates:

Something like water ticks on

Just there, beyond the horizon, just there, steady clock . . .

Go in fear of abstractions . . .

Well, possibly. Meanwhile,

There is a mixing of worlds here; the meditative and the informal live side by side along with the Ezra Pound quote in italics. By juxtaposing these various elements, not only is a singular poetic experience created for the reader, one rich in voices and meaning, but there is also the sense of a conversation being had by the speaker beyond themselves. In approaching the line this way, Wright is able to present Pound himself as well as engage with Pound in the space of the poem.

Second Stop: Kay Ryan

Kay Ryan’s version of what I term indirect clarity and openness of form occurs on a more intimate, yet still indirect, level. To the question “Why do you avoid the hot emotions that are often associated with confessional poetry,” Ryan, in an interview, responds:

“If you put ice on your skin, your skin turns pink. Your body sends blood there. If you think about that in terms of writing, cool writing draws us, draws our heat.”

A good example of what Ryan means here can be seen in this excerpt from her poem “Surfaces”:

Surfaces serve

their own purposes,

strive to remain

constant (all lives

want that).

Here, there is a transparency at the level of craft that is pleasurable: from the internal (indirect) rhyme of “surfaces” and “purposes” as well as “constant” and “want,” to the use of the short line to let the thought develop at a straightforward pace. The language in many ways charms the ear/eye immediately; the indirect clarity and openness of form come into play then when the purpose of this charm is considered. There is gravity to what is being said in such a musical and engaging manner, and one that could easily weigh the lyric down. The subversion of rhyme’s aural appeal to engage casually with a matter that might not necessarily appeal is one of the ways in which Ryan’s work wins me over. In a short, concise statement, the reader is being asked to consider a specific perspective on mortality (“lives/want that”). The decision to place this in a open tone is part of what keeps the reader included and listening closely.

Final Stop: William Carlos Williams

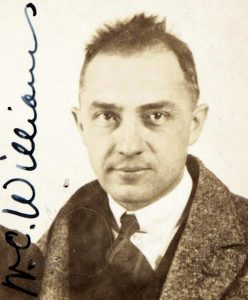

Building off the idea of keeping the reader included and listening closely, I turn lastly to William Carlos Williams. Williams is famous for championing what he calls the American idiom, which he describes in Paterson as “a language which is not English . . . [with] as much originality as jazz.” While much has been written about how these ideas influenced the work of the Modernists, Imagists, Objectivists, and the Beats, there is work being done currently that explores what the American idiom means for Latin@ poets, both in the US and in the rest of the Americas.

Reading through the work of Julio Marzán* and Jonathan Cohen**, I have been heartened to learn about the role Williams’s Puerto Rican heritage played in his work. He was one of the first American poets I know of to have to decide whether to hide that heritage at the level of author name. The story of his having to choose between W. C. Williams, William C. Williams, or to write under his full name is one familiar to Latin@ poets from various backgrounds. The move to stand with “Carlos,” so to speak, is one of the critical moments of subversion in the history of American poetry. Pound often referred to Williams as having “muddled blood”; that Williams continues to be read today with as much pleasure and interest (if not more) than Pound is a testament to Williams and his work as well as a win over such misguided and problematic institutional prejudices.

Williams also chipped away at these prejudices in his actual poetry, often incorporating Spanish into the titles of books and poems. A good example is “El Hombre”:

It’s a strange courage

you give me ancient star:

Shine alone in the sunrise

toward which you play no part.

This short lyric has meant different things to me at various points in my life. When I first read it in my early twenties, I was immediately charmed by the clear logic of the address; it’s the kind of move that nods to the Romantic tradition while being grounded in the Imagist camp. As I grow older, though, the title more and more seems to add another layer, and makes a manifesto out of the four lines. The “Hombre” of the title could easily be the poet, and the courage spoken of could easily be the courage needed to forge ahead in an at times prejudiced literary field, one that bristled at the use of Spanish as much as every day talk in poems.

The arc of Williams and his work is one forged by indirect clarity and openness of form. In his use of Spanish, Williams added to the possibilities and depth of American poetry as well as created a legacy as valuable and influential as his ideas of the variable foot by doing so. I personally connect with this legacy as an American poet with a Latin@ background facing similar decisions on and off the page.

And as a Virgo, I can’t help but see this side of Williams as an innate championing of what would be forgotten, dismissed, or misunderstood.

—

(* Julio Marzán has written about this aspect of Williams’s work in his book The Spanish American Roots of William Carlos Williams. ** Jonathan Cohen edited the book By Word of Mouth: Poetry from the Spanish by William Carlos Williams, for which Marzán wrote the foreword.)