Don Peteroy: For the last four months, I’ve been reading humorous novels exclusively, trying to unpack how humor works, looking for ways the written medium imposes limitations on a writer’s ability to provoke laughter while also granting opportunities that you wouldn’t get in, say, standup comedy or film. I’m particularly interested in how writers sustain humor throughout a novel; I’ve found that most of the books I’ve read are funny for about fifty pages, and then the humor exhausts itself.

Don Peteroy: For the last four months, I’ve been reading humorous novels exclusively, trying to unpack how humor works, looking for ways the written medium imposes limitations on a writer’s ability to provoke laughter while also granting opportunities that you wouldn’t get in, say, standup comedy or film. I’m particularly interested in how writers sustain humor throughout a novel; I’ve found that most of the books I’ve read are funny for about fifty pages, and then the humor exhausts itself.

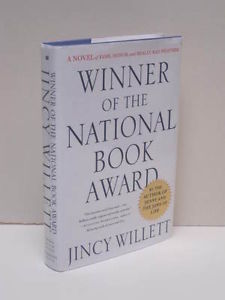

Jincy Willett’s Winner of the National Book Award is one of the few books that kept me laughing until the last page.

Hurricane Pandora is about to strike a town in Rhode Island. Dorcas, the local librarian, is hiding in the library. She busies herself with one of the new nonfiction arrivals, In the Driver’s Seat: The Abigail Mather Story. It’s written by Dorcas’s sister Abigail, and Hilda DeVilbiss, Abigail’s friend. Dorcas isn’t happy about this book—it’s a “wife abuse expose” that chronicles Abigail’s sexual deviance and eventual marriage to the venomous writer Conrad Lowe. While abuse narratives aren’t funny, it’s the book-about-a-book—the metafictional distance—that allows Willett to draw humor from the story of Abigail’s traumatic marriage. Dorcas leads us through the book chapter by chapter; she comments, criticizes, exposes Hilda and Abigail’s embellishments, and reveals what’s been left unsaid.

Winner of the National Book Award shows two competing narratives that tell the same story. Dorcas’s corrective rendition is stylistically sophisticated and brutally honest while In the Driver’s Seat’s is bombastic, sentimental, and full of absurd speculations. For instance, Hilda attempts to explain the primary cause of young Abigail’s excessive sexual appetite, relying on inaccurate psychological explanations:

“Abigail Mather’s great sin was, of course, in growing up. Her father, likely out of his own inchoate sense of guilt, precognizant of his own incestuous desires, withheld from Abigail the male approval necessary to her erotic self-esteem. Just when she had the greatest need of him, he declined to validate her sexuality. . . .”

The humor lies in Dorcas’s mockery and refutation of these fanciful “facts,” her resistance to pop-Freudian psychology.

The characters themselves are pitiful, and it’s their awareness and proud embracing of their deplorable natures that makes them so funny. Conrad Lowe hates women. He’s a former gynecologist who’d been attracted to the field only because he wanted to understand what’s inside women. Then he became a novelist who embodies all of the stereotypical pretensions. In an interview with the Journal-Bulletin, he talks about his latest novel, a thriller called Night of the Gorgon, which is “in the Mantis tradition.” The interviewer asks, “Is that, more or less, the Stephen King tradition?” He responds, “No . . . it is exactly in the Stephen King tradition.”

She asks, “And how do you think your work compares with King’s?”

He says, “It’s worse.”

Willett provides a never-ending procession of satire-conducive excerpts of In the Driver’s Seat; new characters provide fresh surprises, embodying stereotypes pushed to the max: we meet a male “feminist” poet who is obviously a sexist in denial, his enabling wife Hilda, and a depressed Unitarian minister undergoing an existential crisis. The humor endures and escalates in direct proportion to the tragedy because there’s always something outrageous happening, always a twist.