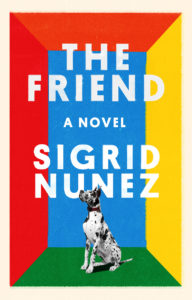

Just in time for the National Book Award ceremony tomorrow, we’d like to share an appreciation for one of the nominees in fiction.

Editorial Assistant Matt Morgenstern: It’s difficult to summarize Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, published earlier this year by Riverhead (and nominated for this year’s National Book Award). Dwight Garner does a good job in the New York Times, though: “This novel’s tone in general, however, is mournful and resonant. It sheds rosin, like the bow of a cello. The woman grieves for her friend, who was her mentor and, if only once, her lover. His dog soothes her; they sleep in the same bed; he is a constant reminder of the man she misses.” At first glance, this is a bare, if not lovable, plot.

Editorial Assistant Matt Morgenstern: It’s difficult to summarize Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, published earlier this year by Riverhead (and nominated for this year’s National Book Award). Dwight Garner does a good job in the New York Times, though: “This novel’s tone in general, however, is mournful and resonant. It sheds rosin, like the bow of a cello. The woman grieves for her friend, who was her mentor and, if only once, her lover. His dog soothes her; they sleep in the same bed; he is a constant reminder of the man she misses.” At first glance, this is a bare, if not lovable, plot.

But The Friend is about much more: contemporary autofiction, contemporary fiction, creative writing programs, overdue #MeToo reckonings, suicide, literary suicide(s), grief, and dog-human relationships. The novel focuses on the unnamed protagonist’s relationship with her late mentor’s Great Dane, Apollo, which comes to resemble a “marriage.” And it is a marriage, but a unique one, bred by longing for something that won’t be there and can’t be there. As the narrator says, “And just because there are other people who’ve lost someone to suicide doesn’t mean that what I’m feeling is something that can be shared.”

Even with that ethereal loss at its center, the “novel” doesn’t demand that something else happen, not really. The happening is its thinking, and The Friend, portentous of a peaking trend in the modern blend of fiction and memoir, is less about its programmatic, memoir-like intellectuality (Virginia Woolf, Marguerite Duras, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others are mentioned) than about what its fictive reality can affect in the reader, namely, grief, anxiety, joy. “Having your dog is like having a part of you here,” the narrator says at one point. To me, this novel is also about the strangeness of “I” and “you.”

As a part of this, The Friend shows pet ownership at its most thrillingly melancholic. A cat-person fiction professor adopting a doomed canine, each finding themselves seemingly concerned for the other’s well-being. A writer who, among other things, observes a dog to this level of particularity: “I see the gray hairs on Apollo’s muzzle and the redness rimming his eyes, I see how stiffly he walks some days, how it sometimes takes two efforts for him to get to his feet, and I ache.”

But, as the late mentor’s first wife says, “the truth is, in this case it’s the animal who can’t deal, and you’re his emotional support human.” We simply can’t know what Apollo feels. This emphasis on anthropomorphized emotion characterizes The Friend: There is something fundamentally unknowable going on here, dog and human alike.

The true value of The Friend is its intimacy. The “you” is destabilized through the text relative to the “I,” so that the “you” can be the lost lover, the real-life inspiration, and/or the dog. When Apollo and the narrator are at the beach, for example, she says, “I see the sun has knocked you out.” It’s a small, cool address. But it’s those sorts of observations and the stories we tell ourselves that let us forget, momentarily, who we are.

Part of what makes a novel fiction rests in this inherent unreality, but that’s how it makes reality itself more accessible. This is why I am a fan of autofiction and happy The Friend is part of that tradition—it’s a genre that shows us how close we are to the fictions we tell ourselves, and each other, to get by.

Matt Morgenstern‘s fiction and nonfiction have appeared in HCE Review, Fairy Tale Review, and Heavy Feather Review. He is a masters student in literary and cultural studies at the University of Cincinnati.