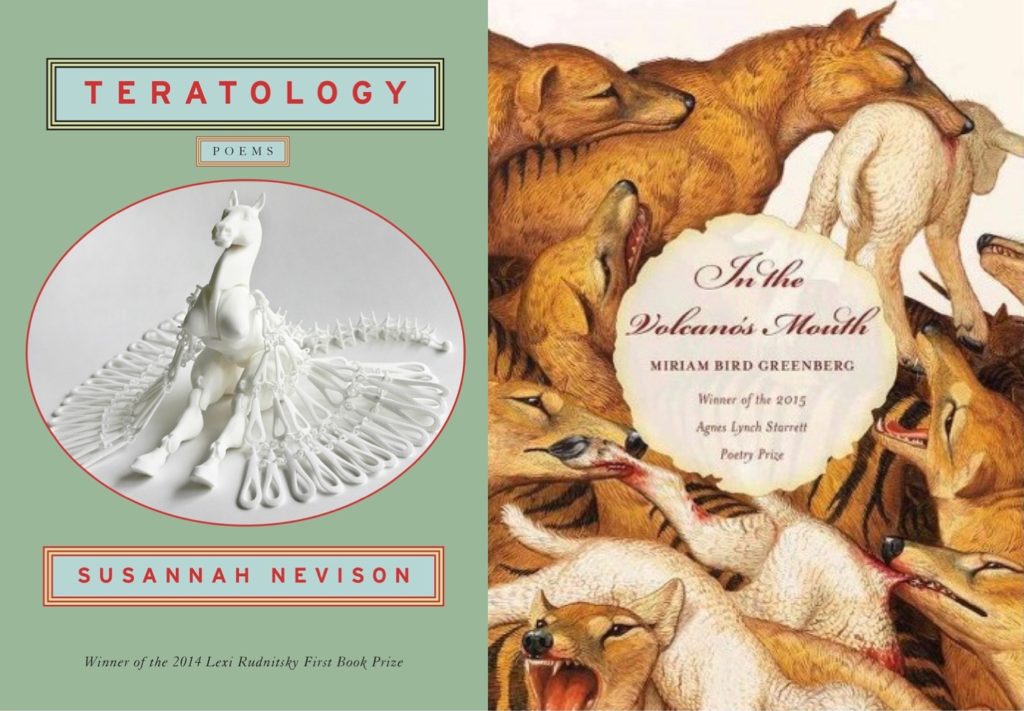

Associate Editor Caitlin Doyle: What better way to honor National Poetry Month here at the CR than to highlight poetry collections by two of our recent contributors? I’ve had the joy of spending time over the past few weeks with Teratology by Susannah Nevison (whose collaborative work with Molly McCully Brown appears in Issue 15.2) and In the Volcano’s Mouth by Miriam Bird Greenberg (who has been featured in our miCRo series and whose work is forthcoming in Issue 16.1).

In Teratology, Susannah Nevison probes what it means to occupy a body, particularly one that has been deemed abnormal. The first piece in the book, “My Father Dreams of Horses,” begins with these lines:

If your daughter is born

and her legs aren’t made

for standing—if her feet

are pointed hooves, if her legs

aren’t made—

The phrase “if her legs aren’t made” echoes powerfully throughout the book as we watch the speaker undergo corrective surgery on one of her legs. Echoing the blurred line between human and animal in “My Father Dreams of Horses,” Nevison invites us, in “Preparing the Animal,” to see a parallel between the doctor’s surgical methods and the way the speaker’s partner field dresses a deer carcass:

What are we but sinew

and synapse, a system’s grim accumulation,

but softer? Soon you will slit

the belly…

In one of the book’s final poems, “Torsion,” Nevison’s gifts come together in full force as she describes the speaker’s post-op session with a physical therapist:

Each tendon’s tender ribbon

pushed against the machine,

against metal pins mapping

the length of my leg—you work

my furious body, work my body

mean and loose.

The sharply patterned rhythmic intensity of the lines allows us to enter the speaker’s experience—the pain, the rage, the hope— in a visceral way as she gives herself over to the recovery process.

The juxtaposition of “each tendon’s tender ribbon” with the “machine” and its “metal pins” in Nevison’s poem resonates with Miriam Bird Greenberg’s emphasis, throughout In the Volcano’s Mouth, on exploring the tension between technology and nature. Greenberg frequently engages in fresh ways with English-language poetry’s long pastoral tradition. Many of her poems examine how our techno-heavy society exists simultaneously in service of and at odds with contemporary rural life. Images of electric wires abound as the collection folds, and it strikes me that these wires provide an effective overarching metaphor for Greenberg’s approach to line-making on the page. In her best lines, pulled taut and charged with conductive energy, she makes our ears reverberate with sounds that multiply the language’s potential range of implications.

In “Killing,” an especially gripping poem from Greenberg’s In the Volcano’s Mouth, the speaker, a young girl, describes the experience of slaughtering a duck for food:

How the blade was not sharp enough.

How a duck’s neck is supple as a thick piece of rope.

… How, even once we plucked her clean and, safe,

someone set a point to boil, traces of her smell

clung to our hands like strands of fog.

How my pulse ran in my fingers

like the heartbeat of another thing.

The girl’s feeling of carrying “the heartbeat of another thing” within her suggests that, through her involvement in the killing of a living creature, she has formed a connection with the animal while also developing a sense of unsettled estrangement from her own body.

The frictions and paradoxes in Susannah Nevison’s “Torsion” and Miriam Bird Greenberg’s “Killing” embody the complexity that distinguishes Teratology and In the Volcano’s Mouth as outstanding debut collections. We couldn’t be prouder to call these two poets CR contributors, and we hope you’ll join us in continuing to follow their work.