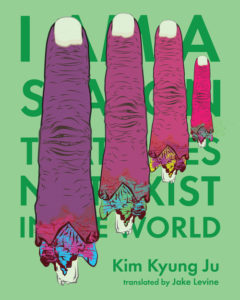

Editorial Assistant Madeleine Wattenberg: I fell asleep halfway through reading Kim Kyung Ju’s I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World (Black Ocean, 2016) and dreamed that a neon pink cobra hid in my shoe and bit my big toe. I mention this both because it is not unlike what it feels like to read this poetry collection (it’s full of unexpected, piercing imagery and causes one to question their embodiment), but also because the dream functions as a central obsession in Kim’s poems. Here, the dream isn’t exactly ephemeral, but instead embedded in physical sensation: “rising through a tiny crack in the window, the smell of the dreams that dead people in the river are dreaming—it’s either that or it’s the smell of dreams that died when the dead were alive.”

These poems undermine assumptions about what it means for a thing to exist. The collection’s title offers a version of this paradox immediately—the ontological affirmation of “I am” is troubled by what follows: “that does not exist in the world.” Kim delineates material and immaterial spaces, only to expose their borders as tenuous.

Similarly, the figures that traverse these spaces (ghosts, the dead, the soul) don’t quite belong in or out of existence either. They’re often located within physical bodies, even the speaker’s body, which creates a spectrum rather than a binary for ontological positioning: “Humans are either born and become ghosts or are born as ghosts who don’t know they are dead already. This I believe. The ghost that doesn’t know it’s a ghost disappears without knowing that it disappeared.” Kim often presents assertions through these contradicting syntactical strategies: either that or this, born or become.

Translated by Jake Levine, I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World is the first collection from the South Korean poet to be released in English. Kim’s background as a playwright and philosopher are apparent throughout his work. Some poems take place in acts. Buddha, Jesus, Kant and Plato cohabitate the language by turn. Rather than treatises, however, the poems most often read as a dialogue between the speaker’s sense of the embodied world and traces of a dis- or unembodied world—what Plato might identify as the world of becoming, between a world of shadow and a world of pure form.

In Kim’s poems, this category might more accurately be labeled unbecoming. Many poems contain fingernail clippings, dead skin, shaved hair, excesses of the body that offer material representation for what grows already dead from the body: “I find a black fingernail on the floor / that I used to play with. / Someday will I too come back in front of the time I lived / and be a roaming dream?” and “Let’s admit language is a name for peeling at the dead skin of life.”

Kim’s poems play in the shadows. They also convey a strong sense of anxiety about the loss of interiority: “It cannot end like this, I thought— / a mass extinction of inner life.” The speaker pursues the heat lost from their body, a heat that correlates with the inner life, because “after the heat of the body is completely erased / a dried life exposes itself.”

The final poem of the collection begins with “Let’s say you and I lied down together in the same place one time.” The invitation inherent to this statement has already expired in the past tense of “lied,” but it still means something to “say” it. This is a different sort of offering, one that exists outside of the world yet still exists in language.

Madeleine Wattenberg’s work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in journals such as Best New Poets 2017, cream city review, The Seattle Review, DIAGRAM, Fairy Tale Review, Ninth Letter, and Mid-American Review. She is currently a PhD student in poetry at the University of Cincinnati, where she also teaches.