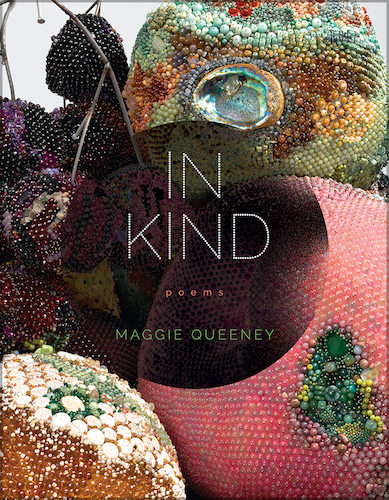

What We’re Reading: In Kind

6 Minutes Read Time

Assistant Editor Holli Carrell: As readers, it is often difficult to articulate why a specific poem, story, or piece of writing speaks to us. I’ve come to believe—at least in my own experience—that this is because language, especially poetry, can move and affect us in ways that are entirely bodily and beyond language. One of my favorite poets, Emily Dickinson, once famously said: “If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me, I know that is poetry.” We all experience and define poetry differently. Still, Dickinson’s portrayal of the poetic encounter comes to the forefront of my mind while reading the poetry of Maggie Queeney in her debut full-length collection, In Kind (University of Iowa Press, 2023).

At a gut level, I am drawn to poetry that communes with the natural world, burns pictures into my mind, and embraces both precision and chaos. More than anything else, I hunger for poetry that allows me to experience the world and language in strange new ways, transforming me outside my experience and viewpoint. Queeney’s poetry in In Kind ticks all these boxes for me while also accomplishing so much more, and perhaps that is because transformation is at the heart of this collection. Like Ovid, Queeney is interested in using her art to speak of metamorphosis, to “tell of bodies changed / to different forms.” In these remarkable poems that shape-shift from villanelle to erasure to abecedarian (and more), Queeney interrogates how trauma is embodied and how rebirth is necessary for survival.

Many poems throughout In Kind communicate how a female-identified body experiences the loss of bodily autonomy from girlhood to womanhood. In the book’s opening poems, we see the speaker as a girl attempting to grasp her own bodily sovereignty and identity in a home environment where femininity and sexual and domestic service are enforced. For instance, in the poem “Font,” the speaker and her sisters escape their reality through storytelling and myth, which offers the girls alternative worlds “where no one ever turns into a girl. / Always a girl into flame, into bird / into rock.” Sewing projects also offer the sisters new ways to reimagine their bodies and futures. Although these artistic outlets provide creative freedom, Queeney shows how gender socialization ultimately disenfranchises the speaker from her own body as a child and adolescent, as we see in the poem “Victim: Root”:

Told what it was to be holy, as a child

I applied the dustiest rose lipstickmy mother owned, chewed the bud

made under the veil stained my cheeks’color, a slight bride in a sheer slip

before the origin that rendered meconquered, as victor clanged a few entries

further.

Queeney brilliantly displays how a young girl is groomed for sex and marriage and how she is made to believe that her worth depends solely on beauty.

In Kind also mediates in moving ways on how a body can heal from gender-based violence and objectification. Queeney frequently draws on the natural and animal world in poems like “My Rough Labor” to question and interrogate relationships between animals, predator and prey, and to offer alternative animal models for resilience and healing:

I learned from the species that devour their own,

the reborn, and those who kill to live: the snake,

the spider, the corvid, and me, mouthingmute into mutable. I took the shapes

of what I ate, rid the old body inside a shudder […]

In this poem, we see that through examining the adaptations of animals, the speaker can transform her silence surrounding the events of her assault into speech, “rid the old body” and begin healing. Similarly, in the villanelle “Scar Wear Song,” Queeney depicts how an animal’s wound-licking response after injury promotes recovery and growth, transforming an open wound into a healed scar. Although the injury and scar will always remain on the animal, she can ultimately heal herself, turning her saliva into a balm and mending the body. Queeney suggests that recovery and healing from trauma can be a creative, life-sustaining, and radical act.

Queeney is also invested in revisionist mythmaking and joins the ranks beside such feminist poets as H.D., Lucille Clifton, Alicia Ostriker, and others working to reclaim women’s voices in myth and challenge preexisting male narratives about women and their bodies. Throughout In Kind, Queeney gives voice to silenced female characters in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, those abused and punished by Gods, transformed from humans into objects and animals—such as Echo, Procne, and Arachne, to name only a few. Queeney’s channeling of these voices is unique in that each transformed character refuses to be broken by their new changed forms, unwilling to be silenced, made less, or othered. For instance, in Queeney’s retelling of the daughters of Minyas myth, the sisters are defiant in their denial of “ecstasy” and their sexualization; they remain firm in their dedication to one another and their art. Even once they are punished by the gods and transformed into bats for their refusal to participate in Bacchus’ festival, they embrace their new animal shapes and futures. As the daughters say collectively at the close of the poem:

We sang ourselves new bodies

the volume of our old hearts.We sang our chests into fists, our blood

into the wine revving our new forms forward.

In Queeney’s translation, the daughters have ownership over their transformation and fate; they are actors, not acted upon.

Ultimately, Queeney communicates in In Kind that the body written on by violence does not need to be the final form, however final that violence may seem at the time. In Kind is a collection I will remember for a long time, profound in its reminder that healing and transformation are always possible, that our old selves can be shed, and that new selves and forms can birthed continually. As Queeney writes in “My Rough Labor”:

Deep in the middle of me, others wait,

each smaller, more perfect than the last,

eyes seamless as pearl earrings.Inside each yolk, the soft bones of her hands and feet

appear identical to the skeletal starts of fins or wings.Identical, the thousand galaxies of gemmy eggs,

my many burning earths, my bodies left, skins shed.

Holli Carrell (she/her) is a writer, editor, and educator originally from Utah, now living in Cincinnati, where she is a PhD Candidate at the University of Cincinnati. Her poems can be found in 32 Poems, The Journal, Salt Hill, Ninth Letter, Bennington Review, and Poetry Northwest, among other places.