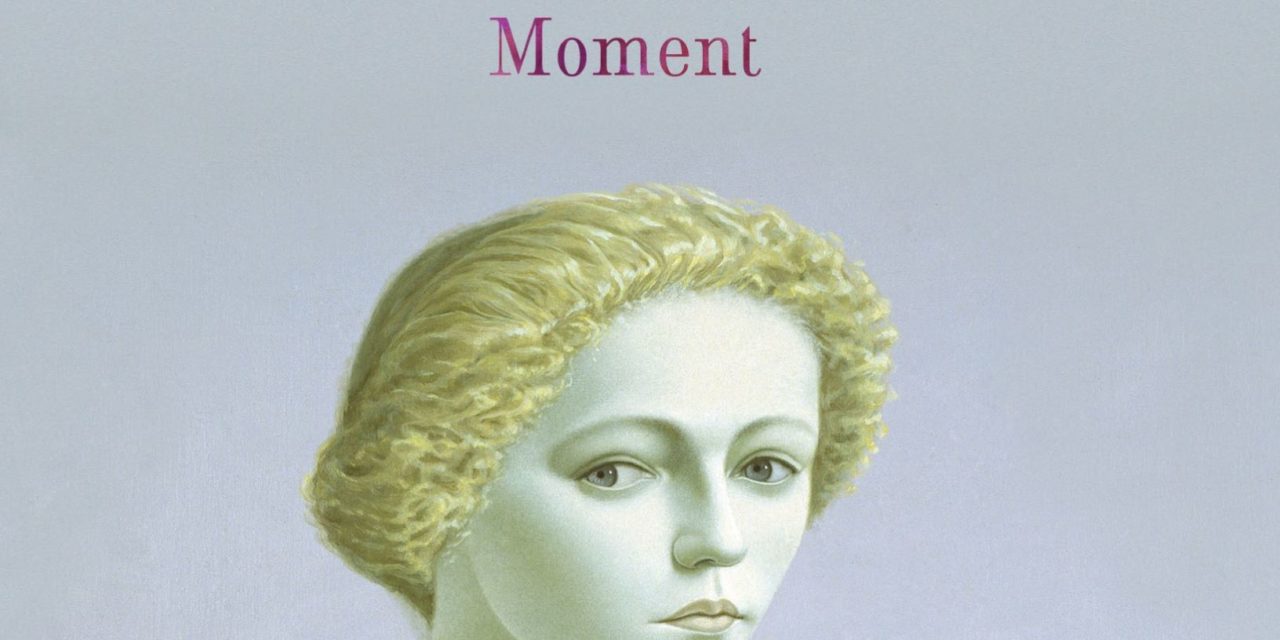

Editorial Assistant Cara Dees: Alessandra Lynch’s third poetry collection, Daylily Called It a Dangerous Moment (Alice James Books, 2017), navigates the trauma of surviving rape, the insatiability and pervasive cruelty of rape culture, and the speaker’s search for a voice as she insists on her own survival and story, to “nearly convinc[e] myself recursiveness / is flight and I am skyward-bent.”

Raw and unflinching, the poems of Daylily occupy a fraught space between silence and voicing silence, writing and the impossible inadequacies of language, memory and its failures, agency and the moment agency is ripped away.

Lynch, who currently teaches in the MFA program at Butler University, expertly negotiates these difficult distances, opening her collection with an epigraph by Theodore Roethke that serves as an entry point and invocation:

Snail, snail, glister me forward,

Bird, soft-sigh me home,

Worm, be with me.

This is my hard time.

The poetry that follows occupies this “hard time,” calling forth elements of nature that conflate with and illuminate the speaker’s body, as in “First air and light suffuse us,” the book’s opening poem: “pin oak leaf, darkening canal, little horses fenced / by highway, clouds, your face.”

In these poems, the body is never far from the natural world, the natural world never far from violence. The lush imagery alternately underlines, contradicts, and serves as antidote to the speaker’s suffering, as in the “Daylily” sequence, when the speaker conjures the addressee:

I could be gone before you’d vanish—

a little weaving in the air, the stir of a twig

enshadowed. Then I felt

the pierce of an arrow, or was it rain.

Nature forms the liminal space between the speaker and her imagination and memory, so that her trauma reverberates through the physical world, into, through, and beyond each of the eight sections of the book.

In an interview with Critical Mass, Lynch states that she “started writing poetry as a way to create another world, a refuge from the chaos and terror that was not of my own making. Maybe my re-making or redefining this terror through metaphor (making it my own) is necessary for me—maybe it’s the fuel for these poems. Maybe this is the way I can inhabit and understand or make something of it, as opposed to allowing it to consume me.” Metaphor allows for a redefinition, a world-making that has the power to reframe or revisit the past, a spell against the forces that would devour you.

In the first section, “Excavation,” a collection of first-person accounts about surviving rape, Lynch shows a close attention to lyricism and music that remains achingly brutal:

The stinging

belt, your buckled hip, the blade

chucking your chin, drawn down your neck,

angling toward the breast.

Don’t ask about the voice that snarled and nested in your ear.

You lived in hoax and hoax is fog. No charm of finches to blast it clear.

The speaker’s dual conversations with herself and with the reader (“Don’t ask about the voice”) echoes again throughout the finishing lines:

His charm: all harm

and names?

His / yours. Don’t ask.

The decades-long pain of the speaker ripples from this poem throughout the third section, a devastating examination of rape culture and the misogyny that harbors it.

The control of girls’ and women’s bodies lies inside the warnings of mothers (“around every bend every swing of road / for a blue van black van what’s windowless scare fast”), in Picasso’s “les demoiselles d’avignon” (“a box with limited shadow / so there was limited light / around them”), in construction workers’ catcalls that lead the speaker to ask, “What else / to do but be a vanished thing?—”

The desire or need to “be a vanished thing” is a complicated one in Lynch’s work. In “Foretell the Silent Ridge of the Tongue,” the speaker rejects the physical human body for one that is disconnected, inviolable, airborne:

I beg to turn back

into smoke, steam, air,

back to what I was

when I hadn’t known

the test and taste of flesh.

Throughout the collection, Lynch vacillates between the first- and third-person, at times addressing an imagined you, the reader, or a self still living in the past. In many of the poems, body and voice remain distant from each other, untranslatable, irreconcilable, such as in “P.S. Assault,” in which the speaker “can’t find the body that belongs to my voice / or my voice that belongs to the harm.”

Nevertheless, despite the speaker’s wish to leave the body behind, it again makes itself felt, so that “something insistently / alive arises from aftermath.” The body persists in its physicality, re-becoming a locus for yearning and memory.

Like Lynch’s other collections, It Was a Terrible Cloud at Twilight and Sails the wind left behind, the poems of Daylily Called It a Dangerous Moment resist consolation and fixed resolution, dwelling in ambiguity and imagery by turns stark and vividly rich, in argument and in fierce love with the body and the world.

Cara Dees is the author of the forthcoming debut collection Exorcism Lessons in the Heartland (2019), selected by Ada Limón for the 2018 Barrow Street Book Prize. The recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a scholarship from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and a Pushcart Prize nomination, she has work appearing or forthcoming in Best New Poets 2016, Crazyhorse, Gulf Coast, Harvard Review, Poetry Daily, The Southeast Review, and elsewhere. She is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Cincinnati.