What We’re Reading: Concentrate

6 Minutes Read Time

Associate Editor Taylor Byas: If I return (begrudgingly) to the pages of my old history textbooks, I am met with the high sheen of those glossy pages, artistic renderings of things and places we have little to no photographic evidence of, figures and charts to help illustrate the particular brand of history taught in schools. At the foundation of my curriculum was always colonial conquest, war, an elaborate flexing of power. This was a history that made America look good. This was a history that was wholly incomplete. I’ve been thinking about the true nature of witnessing, of what it means to interact with our histories. So when I finally read Courtney Faye Taylor’s debut poetry collection, Concentrate (Graywolf, 2022), I was fascinated by how this book models what a fuller, rounder account of history can look like.

Taylor’s background as both a poet and visual artist shine through in this collection, in collages, clippings of images, small drawings, and photographs taken by the author herself. Across these different mediums, Taylor documents the history of Latasha Harlins’s murder by a Korean shop owner who falsely accused Latasha of stealing a bottle of orange juice. But unlike the history books of my childhood, Taylor’s history is alive on the page, feels close enough to change.

You might still be thinking of your old college textbooks and saying, But these had images and photographs too, and you’d be right. But I also remember feeling so distant from those images, some merely sketches or drawings of places that no longer exist, others black-and-white photos of what felt like another world. Even as I interacted with those images, those people and places remained inaccessible, impossible to truly conjure up in my mind. In Concentrate, Taylor takes her reader along with her on a photographic journey in Los Angeles, where she visits places Latasha frequented during her life, the place of her death, and finally the cemetery where Latasha was buried. For a while, I didn’t understand what was at the root of my strong emotional response to these pictures, but then I realized that it was my own discomfort. Just over a month before reading this book, I’d gone to LA for the first time. In my mind, LA easily took shape, its architecture and aesthetic now recognizable in the old photograph of Empire Liquor. On the next page, Taylor provides a photo of the new market that stands in its place, Numero Uno Market, and a few pages later, I am given Taylor’s stark black-and-white photograph of the juice fridge inside of the store. Beneath it, Taylor writes “But there are no signs of murder, memorial, or resistance when I arrive. The ground is like any ground. Normalcy devastates. Stillness lies to me” (68). By documenting this physical (even architectural) erasure of Latasha’s murder, Taylor both forces us to witness the erasure and simultaneously unravels it. Her photographs of the eerie normalcy coupled with her poetic captions and interactions with the photos work together to re-narrative these spaces, to write the stories back into them.

Taylor is also transparent about her research journey, openly explaining her process and walking her reader through her journey in LA. It might seem counterintuitive to include the present within a text so heavily concerned with history, but Taylor demonstrates the importance of documenting both history and our interaction with it, as how we interact with history can change the very shape of it. A powerful example of this takes place when Taylor visits the mural of Latasha on the side of a rec center and learns that Latasha was a poet. In one of the book’s most emotional moments, Taylor realizes that Latasha’s poem is like an “I am” poem that Taylor herself had written in 2004, then includes a picture of her old poem. In this moment, the distance between Latasha’s history and Taylor’s history is collapsed, and Taylor’s own poem seems to be redefined by Latasha’s; Taylor writes, “My poem, maimed by fear of catastrophe, of breath in the inanimate, unbridled anxiety. But in Latasha’s work, there’s uninterrupted possibility. Reading her lines, I bear witness to how a Black girl once spoke life into herself” (79). Taylor’s words are reframed and complicated by Latasha’s. Their words together also speak to a collective and shared Black girl experience and language.

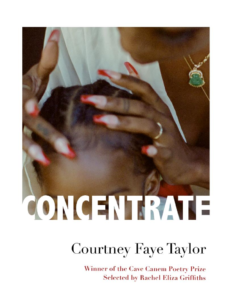

And the idea of “collective” is foundation to this collection. The title Concentrate itself is multiple things at once. It is reference to the orange juice that Latasha was accused of stealing before her murder, emphasized by small drawings or orange slices throughout the collection. It is a command from both Taylor and the Aunt Notrie that appears in the collection. The book opens with a conversation between the speaker and Aunt Notrie while Aunt Notrie presses the other’s hair. This space the two women inhabit is sacred and culturally important, as advice, lessons, and stories are passed down during these conversations. Aunt Notrie first tells us what “concentrate” means, saying “Did that deaconess teach you the longest / meaning of concentrate? hold your ear / down A strong, hard focus” (10). Aunt Notrie passes this wisdom onto the speaker, and Taylor, by letting us in on the conversation, passes it along to us, asks us to enact this strong, hard focus as we learn Latasha’s full history. Lastly, according to Merriam-Webster, to “concentrate” is to also “gather into one body, mass or force.” Through this diverse curation, Taylor underscores the importance of more honest witnessing, of a history that includes all the moving parts, including ourselves.

Taylor Byas (she/her) is a Black Chicago native currently living in Cincinnati, Ohio, where she is now a PhD candidate and Yates scholar at the University of Cincinnati, an assistant features editor for The Rumpus, and a poetry acquisitions editor for Variant Literature. She is the author of the chapbook Bloodwarm from Variant Literature, a second chapbook, Shutter, from Madhouse Press, and her debut full-length, I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times, forthcoming from Soft Skull Press in August of 2023. She is also a co-editor of The Southern Poetry Anthology, Vol X: Alabama, forthcoming from Texas Review Press, and of Poemhood: Our Black Revival, a YA anthology on Black folklore from HarperCollins. She is represented by Rena Rossner of the Deborah Harris Agency.