Antechamber – Joshua Coben*

The father is a dark door

the son may lean against

to listen for the locked room

of himself, his next life.

Later he will listen there

for the echo of his own

death. Meanwhile he becomes

a dark door for someone

else. It takes him years

to grow so broad and smooth,

so wooden and closed. He does

not feel the ear of his son

pressed close and listening.

José Angel Araguz: The best poems have an ability to refresh our everyday world, and even have us looking closer at how we define that world. In “Antechamber,” Joshua Coben uses the metaphor of a door to inhabit ideas of being locked out and bring them into the emotional realm of familial roles. The speaker’s straightforward tone charges the short lyric with the certitude of allegory; meanwhile, what develops within that allegory is made up of the uncertain. This back-and-forth movement creates a tension that evokes the restlessness born out of what is unspoken. When so much of human experience is made up of listening at the “door” of one another, poems like this one help us to make sense of what we catch.

Speaking of doors, this poem had me thinking also of Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and transitions. He is typically portrayed as having two faces, one looking to the future while the other looks to the past. Coben’s poem taps into this simultaneity; the speaker’s meditation, in a way, is a statement on how self is made up only in part of social roles, and never strictly defined by them.

Speaking of doors, this poem had me thinking also of Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and transitions. He is typically portrayed as having two faces, one looking to the future while the other looks to the past. Coben’s poem taps into this simultaneity; the speaker’s meditation, in a way, is a statement on how self is made up only in part of social roles, and never strictly defined by them.

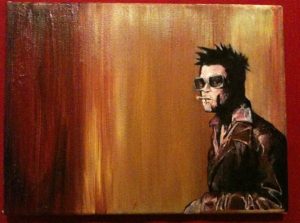

A similar sentiment is expressed by Tyler Durden in Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club:

You’re not your job. You’re not how much money you have in the bank. You’re not the car you drive. You’re not the contents of your wallet. You’re not your fucking khakis. You’re the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.

Taken on their own, these words work on the other side of the spectrum Coben’s poem inhabits. The impetus is the same – a brief exploration/explanation of what the self is – but Palahniuk’s character engages ideas of self through being heard rather than through listening.

Taken on their own, these words work on the other side of the spectrum Coben’s poem inhabits. The impetus is the same – a brief exploration/explanation of what the self is – but Palahniuk’s character engages ideas of self through being heard rather than through listening.

The poem and novel’s messages meet on the page, itself a “dark door” where the reader listens in.

*reprinted with permission from the author. Originally published in issue 12.2.