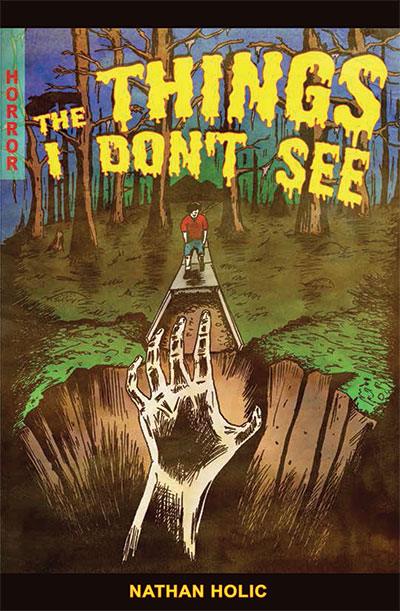

Don Peteroy: Hemingway notes that in effective prose, writers will omit aspects of the story, but the reader will nonetheless sense the presence of what’s not there. “The dignity of the movement of an ice-berg,” Hemingway says, “is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” Likewise, in Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud describes the empty, transitional space between comic panels as a potent ground for the untold story beneath the surface. Nathan Holic’s novella, The Things I Don’t See, exemplifies McCloud and Hemingway’s theories of omission through conventional storytelling and comic graphics, creating a haunting and sometimes terrifying reading experience. Though it’s marketed as a horror novella, you won’t encounter haunted houses or monsters. The ghosts in this story are our own monstrous secrets, refusing to be brought into the light.

Don Peteroy: Hemingway notes that in effective prose, writers will omit aspects of the story, but the reader will nonetheless sense the presence of what’s not there. “The dignity of the movement of an ice-berg,” Hemingway says, “is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” Likewise, in Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud describes the empty, transitional space between comic panels as a potent ground for the untold story beneath the surface. Nathan Holic’s novella, The Things I Don’t See, exemplifies McCloud and Hemingway’s theories of omission through conventional storytelling and comic graphics, creating a haunting and sometimes terrifying reading experience. Though it’s marketed as a horror novella, you won’t encounter haunted houses or monsters. The ghosts in this story are our own monstrous secrets, refusing to be brought into the light.

Craig, aspiring to live life like a “sitcom dad,” has relocated his wife and step-son to a developing community outside of Orlando. Unfortunately, Phase II of the construction is cancelled when the recession comes, and Craig’s family is surrounded by unfinished homes, dirt roads, muddy craters, and the unfulfilled promise of a pool, a clubhouse, and communal happiness. His step-son, Taylor, was already a “problem child” before they’d arrived in the ghost-community, but its emptiness seems to have exacerbated his growing hatred toward Craig. A horror film fanatic, Taylor draws pictures of Craig being murdered in the most gruesome ways. The child’s violent fixations become the object of his step-father’s obsession, culminating in a power struggle. Each chapter alternates between timelines conveying Craig’s childhood and present. Even as Craig reluctantly confesses the truly horrific things he’d done as a child, we see him “investigating” Taylor, attempting to preempt or prevent what Craig believes will be Taylor’s intricate, bloody revenge. He knows Taylor is keeping dangerous secrets because that’s what he’d done as a child, and presumably, that’s what all boys do:

“. . . we were children and we believed our own lies and we were fucking evil, everything that an adult should be afraid of. And I don’t care how many diapers you change or how many loving glances you receive from your baby, you don’t know what children are capable of when your eyes are shut, when the clouds choke out the sun. A damaged child, full of hate? Shit. Best not to shut your eyes.”

Craig discovers on Taylor’s computer a series of animated drawings that are difficult to see as anything other than a promise of destruction, yet we can never be sure what Taylor’s drawings are telling us, or what the story between the frames actually is. Either way, both Craig and Taylor show signs of psychopathic potential, and by the final scene, we’re not sure who is going to do the killing, or if there will be any at all.

I’ve read a lot of horror stories, and those without the ghosts or murderers (Shirley Jackson comes to mind) can be just as terrifying as those with these elements, sometimes more. Aside from Holic’s ability to render sophisticated characters, his sentences are alive with haunting details of an abandoned suburbia, idiosyncratic in voice, poetic at times, and attentive to the power of each word. When horror writers actually care about the prose (about half do)—get this—the sentences intensify the thrills in the plot. Holic wants his readers to believe and feel the terrors on the page, and he succeeds by raising the bar with careful, artful prose. In 126 pages, he manages to juggle multiple themes, which pull the reader in as effectively as the sentences: aging, brotherly rivalry, the death of a loved one, abandonment, 1980s nostalgia, peer pressure, middle-class ennui, denial, passivity, honesty, humility, and ultimately, what it means to be a father.

You can purchase The Things I Don’t See from Main Street Rag Publishing at http://mainstreetrag.com/bookstore