Becky Adnot-Haynes: As a third-year doctoral student here at UC, I’m currently studying for exams, which means that my days are divided evenly between my work as an assistant editor at CR and reading lots and lots and lots of books. And then reading some more books.

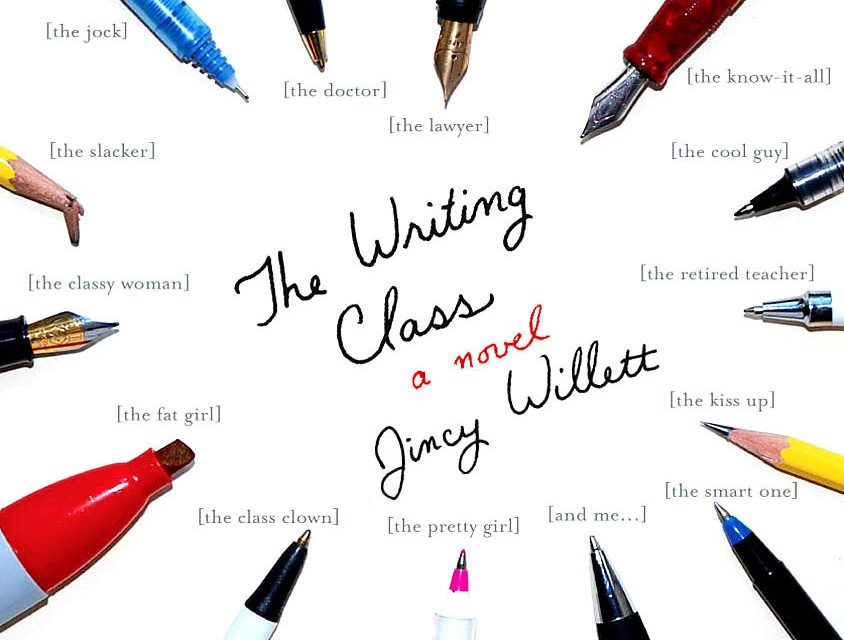

One of the books I’m enjoying right now is Jincy Willett’s excellent novel The Writing Class. It belongs to one of those genres rarely attempted by contemporary writers: the literary murder mystery, or—as I like to think of it—the workshop whodunit. Protagonist Amy Gallup, who hasn’t published a novel in decades, teaches a community writing class to keep herself financially afloat and to combat her reclusive tendencies. As in real-life workshops, the fiction in the class runs the gamut from lackluster to predictably competent to shockingly outstanding. The difference is that the actions of a class prankster, identity unknown, quickly go from annoying to menacing. For anyone who has ever taught (or taken) a workshop, the characters will ring true, and it’s laugh-out-loud-and-slap-your-knee funny. The novel’s hero, Gallup, shines most brightly in a sparkling lineup of characters.

One of the books I’m enjoying right now is Jincy Willett’s excellent novel The Writing Class. It belongs to one of those genres rarely attempted by contemporary writers: the literary murder mystery, or—as I like to think of it—the workshop whodunit. Protagonist Amy Gallup, who hasn’t published a novel in decades, teaches a community writing class to keep herself financially afloat and to combat her reclusive tendencies. As in real-life workshops, the fiction in the class runs the gamut from lackluster to predictably competent to shockingly outstanding. The difference is that the actions of a class prankster, identity unknown, quickly go from annoying to menacing. For anyone who has ever taught (or taken) a workshop, the characters will ring true, and it’s laugh-out-loud-and-slap-your-knee funny. The novel’s hero, Gallup, shines most brightly in a sparkling lineup of characters.

The best thing about the book is the way that Willett manages to intertwine the workshop satire with the murder mystery, making the two narrative elements lean on one another for necessary support, the mystery affecting the class’s writing and vice versa: When a student calls Amy to tell her that he has received a threatening note, she interrupts him to ask about the placement of a comma. It’s a mystery solved through syntax: What more could an editor want?

Lisa Ampleman: Like Becky, I’m compelled to devote most of my reading these days to my comprehensive exam lists. Up this week: Anne Sexton, Elizabeth Bishop, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, and some medieval troubadour poems.

However, I’ve made an exception for Rosanna Warren’s new collection, Ghost in a Red Hat. What I’ve long loved in Warren—her vigorous diction and meticulous evocation of image—are amply displayed in these new poems. For example, “At the Lake” begins with a familiar trope—description of landscape—re-envisioned: “We sat at a picnic table at the edge of your lake in honeyed September/ as wavelets fractured sky-bits, sun-bits, distant/ russet hill-shapes into hill-shards.” The rest of the poem moves with similar energy, describing the scene with as attentive (and as carefully emotional) an eye as Elizabeth Bishop’s. Those fractured images and hyphen-split words echo a terminally ill character’s revelation late in the poem that “I may not come through this,” and this poem, part of a powerful series remembering Warren’s friend Deborah Tall, is not atypical, as the elegiac lyric underlies much of the collection.

However, I’ve made an exception for Rosanna Warren’s new collection, Ghost in a Red Hat. What I’ve long loved in Warren—her vigorous diction and meticulous evocation of image—are amply displayed in these new poems. For example, “At the Lake” begins with a familiar trope—description of landscape—re-envisioned: “We sat at a picnic table at the edge of your lake in honeyed September/ as wavelets fractured sky-bits, sun-bits, distant/ russet hill-shapes into hill-shards.” The rest of the poem moves with similar energy, describing the scene with as attentive (and as carefully emotional) an eye as Elizabeth Bishop’s. Those fractured images and hyphen-split words echo a terminally ill character’s revelation late in the poem that “I may not come through this,” and this poem, part of a powerful series remembering Warren’s friend Deborah Tall, is not atypical, as the elegiac lyric underlies much of the collection.

So, too, does careful reading of world literatures and cultures. The title poem describes a girl growing up in Italy, enigmatically reciting Petrarch in order to become “picturesque,” and the rest of the collection references The Odyssey and the Koran, and describes French, Italian, German, and Iraqian landscapes. The poems do not exoticize; instead, they apply that careful eye to what remains in these places despite the erosions of time. In “Mistral II,” Warren writes, “It was I who prayed/ yesterday to make this refuge cry with a different breath,/ hoping some new word would be snatched up out of my throat.” I found many such new words in Ghost in a Red Hat.