Nicola Mason: Last week, Michael (the fiction editor) looked up from his reading and asked, “What words do you see that are frequently misspelled?”

Nicola Mason: Last week, Michael (the fiction editor) looked up from his reading and asked, “What words do you see that are frequently misspelled?”

“Cemetery,” I said, “minuscule, seize, graffiti, mantel—the fireplace thing—as opposed to mantle—the cloak thing. What about you?”

“Discreet—the keep-it-to-yourself thing—as opposed to discrete—the singular-bits thing—Caribbean, liquefy, genealogy. What else?”

“People always use poured when they mean pored. And Cincinnati,” I said. “It’s surprising how often people stick an extra t in there.”

“Millennium,” he said, “sacrilegious, fluorescent.”

“Millennium,” he said, “sacrilegious, fluorescent.”

“Vocal cords,” I said, “with an h.”

“Yes!” he cried. “With an h.”

“Foreword,” I said.

“Epigraph,” he said. “Not epigram.”

“Not epigram.” I nodded. “Nyet.”

Michael rested his chin on his thumb. “How can we help the spelling challenged?”

“I’ve got it,” I replied. “We can quote Words into Type. On the blog. Everyone who’s anyone reads the blog.”

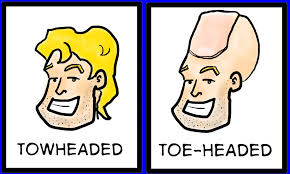

“Whose,” he said, “when they mean who’s. And vice versa.”

“Vice,” I said, “when they mean vise.”

“Such as this passage?” he inquired: “The writer who is a poor speller should work with a dictionary always at his side and should send out no manuscript, proposal, or outline without carefully checking doubtful words and proper names.”

“Indeed,” I said. “And this one: Words often misspelled should be memorized or written on a list for future reference.”

“Good one,” commended Michael.

“Thanks,” I said. “I’m glad we had this very spontaneous talk about the building blocks of our wonderfully expressive language.”

“Ditto,” Michael replied, making a little gun with his index finger and thumb, then shooting it at me. “What do you say we get back to our reading?”

I nodded, leaning toward my computer screen and inhaling. “I love the smell of fresh submissions.”