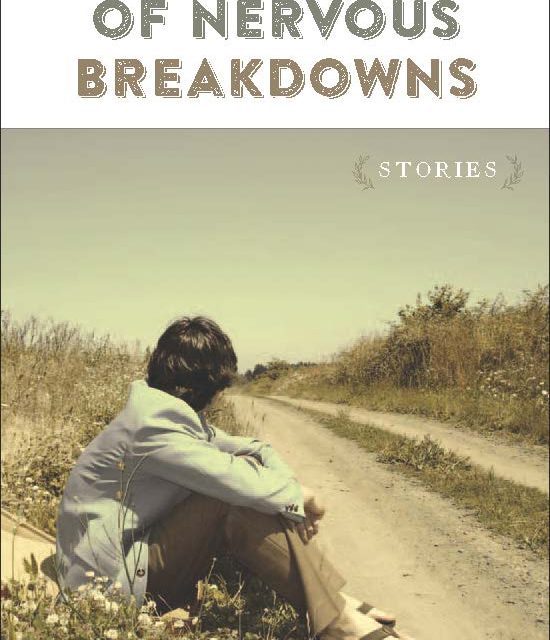

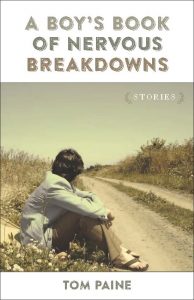

We’re doing something unusual with this feature—running a piece from our pages (in this case a story in our current issue, “It Was Just Swimming” by Tom Paine) in its entirety on our blog. We hope to present you with more such content in the future, and we are grateful to LSU Press for allowing us to reprint the story, which will appear in Tom Paine’s collection, A Boy’s Book of Nervous Breakdowns, this October. Below we offer commentary from volunteers and staff members Katie Knoll, A’Dora Phillips, and Nicola Mason, as well as remarks by the writer on his work. To read “It Was Just Swimming,” click here.

We’re doing something unusual with this feature—running a piece from our pages (in this case a story in our current issue, “It Was Just Swimming” by Tom Paine) in its entirety on our blog. We hope to present you with more such content in the future, and we are grateful to LSU Press for allowing us to reprint the story, which will appear in Tom Paine’s collection, A Boy’s Book of Nervous Breakdowns, this October. Below we offer commentary from volunteers and staff members Katie Knoll, A’Dora Phillips, and Nicola Mason, as well as remarks by the writer on his work. To read “It Was Just Swimming,” click here.

From A Boy’s Book of Nervous Breakdowns: Stories by Tom Paine, Copyright © 2015. Reprinted by permission of LSU Press, lsupress.org. All rights reserved.

Katie Knoll: Tom Paine’s “It was Just Swimming” is the perfect example of a story going where you’re convinced it won’t, where it can’t—where, in its first lines, it has already promised to go. “They asked the clerk at the Best Western if the water was safe. . . . of course it was safe!” Reminiscent of Flannery O’Connor in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” Paine lets disaster lurk in every line, capturing the strangeness and danger of a day on the Florida beaches. The story’s roving gaze makes each image unexpected, each action as surreal as the next. “People up and down the beach baked under a sherbet of umbrellas. The American flag was snapping. The sky was plutonium blue. He was going to ask his girl to marry him tonight.” The piece has this delightful willingness to just experience itself—the world it creates—and the mind of the man who takes it all in. This willingness to just see lends a wild energy in the piece, which races from grandmothers giving tongue-kisses to asphyxiating boys to car-chase scenes, all while maintaining the kind of heart-stopping line-writing like “when the sunset murdered the sky.” “It Was Just Swimming” left me reeling; eager to stay in Paine’s world, a little scared to get out of it.

A’Dora Phillips: Who doesn’t wonder what might be lurking in the ocean’s depths? In “It Was Just Swimming,” this ubiquitous sense of unease adds to the bewitchment in the story’s backdrop: Is the water enchanted or dangerous? The eerie slipstream mode Paine has adopted works well to create an elusive sense of what is real. The trouble, we might think, is the narrator himself, who has “gotten weird lately,” his impressions warped as his mind feverishly travels from thoughts of his pregnant girlfriend giving birth in a Jacuzzi to perceptions of the Kodachrome-brilliant beach. At the vacation hotel, the clerk seems too old to have children, yet his “twin boys” are out there, catching silver minnows. When there’s “something grainy,” some “weird alien stuff” on the protagonist as he surfaces from the waves, we don’t necessarily realize that we ought to be on alert. The kind of person who throws himself into experience, our narrator takes in stride the water tasting of Clorox, his burning eyes.

Though the story is securely anchored in contemporary reality, Paine is preoccupied with the “tripline of miracle” that surrounds his characters. Instead of the old fisherman and his wife, instead of the lighthouse keeper, Paine gives us the twenty-first-century seekers: the narrator, his girlfriend Catalina, and his friend Jimbo. And when the inevitable occurs and something does emerge from the water, something terrible, you wonder why more writers are not reconditioning the ancient tropes of storytelling in light in today’s real-world horrors.

Though the story is securely anchored in contemporary reality, Paine is preoccupied with the “tripline of miracle” that surrounds his characters. Instead of the old fisherman and his wife, instead of the lighthouse keeper, Paine gives us the twenty-first-century seekers: the narrator, his girlfriend Catalina, and his friend Jimbo. And when the inevitable occurs and something does emerge from the water, something terrible, you wonder why more writers are not reconditioning the ancient tropes of storytelling in light in today’s real-world horrors.

Nicola Mason: “It Was Just Swimming” is a masterpiece of pitch. It hits the highest register in almost every paragraph, and though Paine never swings away from this extreme mode of expression, the tone modulates, toggles back and forth, blends, lending the pitch wildly varying shades of emotion. He’s like a virtuoso playing a one-stringed violin. What begins as jubilance (“It was 101 degrees out! Who wouldn’t charge the ocean? The ocean was liquid salvation! God’s own swimming pool!”) merges with incredulity as the narrator and his pal Jimbo encounter a strange substance in the surf (“The only way to get the waxy orange stuff off was to go at it with plastic knives from the dining room of the Best Western. Even then a couple of layers of skin were lost!”). Soon thereafter, alarm enters in (“He scooped up the kid who was clawing the air. The beach was spinning under him, but he charged with the boy to his Harley. Taking action!”), followed by outrage (“Those twin kids were just playing on Fort Walton Beach! Building a sand castle like every other American kid in summer! That’s not supposed to be playing with napalm! There was something in the water! In the water!), fear (“They zapped Jimbo’s heart with the paddles. Handlebar doctor glared up at the red numbers of the digital clock and stopped compressions. Handlebar stopped compressions!”), confusion (“It was like every pore in his body was leaking at once. But he had no temperature! You can’t sweat buckets without a spike in temp! He was coming back negative—negative negative negative—on all the tests.”), and an odd form of realization (“A lot of these guys had been his sworn enemies. Jesus! They were going to miss him!”). The story does not relent until everyone—characters and readers alike—are inhabiting the same charged consciousness, feeling the same pervasive dread, the same stunned grief. Then—in the final line—it releases us, grimly, beautifully.

And yet as tragic as the piece becomes, there is something about its excess that reminds one of those movies titled “Outbreak,” “Contagion,” “Carriers,” “Quarantine.” It is grandly, madly tragic; even absurdly so as odd moments of humor slip in (“Jimbo had the other kid by the hand and was telling him to keep gargling Coke. Jimbo had a strange faith in the curative power of Coke”); or bits of bloviation (“No, he wanted to be more help, he did! But he was a shrimper, not a doctor”); or melodramatic medical gobbledygook (“I’ve got four autopsies already of people who went swimming today. I’ve seen dissolved esophagus, enlarged hearts, and we’ve got samples of ethylbenzene, m-xylene, hexane-2, 3-methylpentane, and isooctane. . . . This guy’s body is full of things you wouldn’t believe.”)

And yet as tragic as the piece becomes, there is something about its excess that reminds one of those movies titled “Outbreak,” “Contagion,” “Carriers,” “Quarantine.” It is grandly, madly tragic; even absurdly so as odd moments of humor slip in (“Jimbo had the other kid by the hand and was telling him to keep gargling Coke. Jimbo had a strange faith in the curative power of Coke”); or bits of bloviation (“No, he wanted to be more help, he did! But he was a shrimper, not a doctor”); or melodramatic medical gobbledygook (“I’ve got four autopsies already of people who went swimming today. I’ve seen dissolved esophagus, enlarged hearts, and we’ve got samples of ethylbenzene, m-xylene, hexane-2, 3-methylpentane, and isooctane. . . . This guy’s body is full of things you wouldn’t believe.”)

The story is both horrifying . . . and entertaining. It gives you that gut-sick feeling . . . and makes you snort. It is, to use an old simile of my dad’s, as serious as a wolf in the woods, yet it’s also a spoof of sorts. With “It Was Just Swimming,” Tom Paine creates a new genre: the contemporary eco-disaster black comedy.

Tom Paine: I’m a little uncomfortable with writing about a story. Commenting on one’s work means using the word “I” a lot, and maybe that’s why I moved to fiction. The anonymity. But here goes: Corexit. We sprayed Corexit, a cousin of Agent Orange, all over the Gulf after the BP oil spill. Corexit adhered to the oil and pulled it out of sight to reduce BP’s liability. But Corexit made some Floridians very, very sick. Medieval boils and pox and vomiting and death. Not to mention we left the Gulf an ecological septic tank and took a very oily shit on the sealife. So the story seems like SciFi, but is based on testimony. People really did have these horrible allergic reactions and died–not that it made the news. We live in a time when water and skin–the simplest relationship– is in question. What happens to the ancient sea-loving soul when the sea is poison?