On Our Poetry Winner, “Very Many Hands” by Aaron Coleman

Poetry Editor Don Bogen: “Very Many Hands” stood out among this year’s strong field of contest entries for, among other things, its overall ambition: It’s the first multi-unit poem to win the award, and it more than meets the challenges that a longer work entails. I was struck by the fine combination of unity and variety among the paragraphs—we’re always in one poem, but it stays fresh over the long haul, with room to shift and surprise. The energy and drive of the piece unit by unit, sentence by sentence, and phrase by phrase, are impressive indeed, the rhythms both intricate and forceful. With images that take us everywhere from a church pew to “man-high seas of crops,” from the Underground Railroad to the San Diego shipyards, “Very Many Hands” is a vivid exploration of past and present, self and others. The poem is big, smart, sensitive, and deft.

Aaron Coleman: We’re living inside a time where many of the myths that have carried us don’t hold the same strength—or at least don’t hold the same meanings—they once held. This prose poem form, trapped and raving inside itself, pushing against those boundaries from within, calls to mind, for me, Terrance Hayes’s concept of “wind in a box.” These paired verse paragraphs, in each page’s dialectic, scramble to push for new parameters wherein an identity might make a home; those parameters, out of necessity, struggle to come to terms with the mess of history, memory, family, religion, shame, guilt, violence, desire . . . I find myself often struggling to work through these topics in a way that feels productive in my poems, and in the case of “Very Many Hands,” and often, I find the doorway in through personal vulnerability, perilously through my body and the bodies of those I love. I hope what comes through in the poem, on some level, is a dynamic and recalibrated spectrum of desires; what happens to us when we work to acknowledge their complexity, and complicity?

Aaron Coleman: We’re living inside a time where many of the myths that have carried us don’t hold the same strength—or at least don’t hold the same meanings—they once held. This prose poem form, trapped and raving inside itself, pushing against those boundaries from within, calls to mind, for me, Terrance Hayes’s concept of “wind in a box.” These paired verse paragraphs, in each page’s dialectic, scramble to push for new parameters wherein an identity might make a home; those parameters, out of necessity, struggle to come to terms with the mess of history, memory, family, religion, shame, guilt, violence, desire . . . I find myself often struggling to work through these topics in a way that feels productive in my poems, and in the case of “Very Many Hands,” and often, I find the doorway in through personal vulnerability, perilously through my body and the bodies of those I love. I hope what comes through in the poem, on some level, is a dynamic and recalibrated spectrum of desires; what happens to us when we work to acknowledge their complexity, and complicity?

I’m interested in the context that a place like Cincinnati might have for a poem like this, on the border of the crucial Ohio River between mythical (and at the same time, dangerously real) North and South, and a pivotal space of the Underground Railroad. Being from the Midwest and having lived around it, I see this poem as born out of our schizophrenic (here I mean “split mind,” in the sense of the word’s Greek roots) midwestern spaces.

Aaron Coleman is the author of St. Trigger, which won the 2015 Button Poetry Prize, and Threat Come Close (Four Way Books, forthcoming 2018). A Fulbright Scholar and Cave Canem Fellow from Metro-Detroit, Coleman has lived and worked with youth in locations including Kalamazoo, Chicago, St. Louis, Spain, and South Africa. He’s recent graduate of Washington University in St. Louis’s MFA Writing Program and former Public Projects Assistant at Pulitzer Arts Foundation. Recent poems have appeared in Apogee, Boston Review, Fence, Greensboro Review, Pinwheel, River Styx, Tupelo Quarterly, Southern Indiana Review, and elsewhere. He is currently a PhD student in Washington University in St. Louis’s Comparative Literature Program.

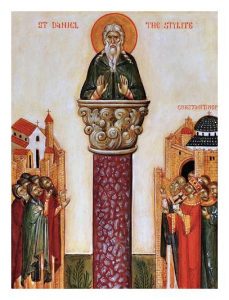

On Our Prose Winner, “Stylites Anonymous” by Maureen McGranaghan

Fiction Editor Michael Griffith: “Stylites Anonymous” stood out among a strong field of nearly 600 prose contest entries for its imaginative conceit—that grail I hadn’t even known I was looking for, the Great American Pole-Sitting Story—but even more so for the way that, with a depth of ambition that reveals itself bit by bit, it wittily explores big themes: faith, family, addiction, love, spectacle and asceticism, and more.

Maureen McGranaghan: I first learned about stylites, monks who live atop poles, from William Dalrymple’s 1997 book From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East. It was fascinating from beginning to end. In 1994, Dalrymple set off from Mount Athos in Greece and spent six months traversing the Levant to arrive at the Coptic monasteries of Upper Egypt. His book is a survey of the old Byzantine Empire and an exploration of its Christian communities, past and present. I was especially struck (and frightened) by the fierce asceticism of Byzantine monks, who crammed themselves into crawl spaces, locked themselves in hanging cages, or lived atop “styles,” as the poles came to be known, for years at a time. Nor have stylites necessarily died out; Dalrymple interviewed a Syrian monk in Aleppo determined to resurrect the practice (though it’s unlikely his community has survived the current civil war).

Maureen McGranaghan: I first learned about stylites, monks who live atop poles, from William Dalrymple’s 1997 book From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East. It was fascinating from beginning to end. In 1994, Dalrymple set off from Mount Athos in Greece and spent six months traversing the Levant to arrive at the Coptic monasteries of Upper Egypt. His book is a survey of the old Byzantine Empire and an exploration of its Christian communities, past and present. I was especially struck (and frightened) by the fierce asceticism of Byzantine monks, who crammed themselves into crawl spaces, locked themselves in hanging cages, or lived atop “styles,” as the poles came to be known, for years at a time. Nor have stylites necessarily died out; Dalrymple interviewed a Syrian monk in Aleppo determined to resurrect the practice (though it’s unlikely his community has survived the current civil war).

I can hardly imagine life atop a pole; it seems uniquely terrifying (I don’t love heights), uncomfortable, and maybe transcendent. What would someone’s daily schedule look like up there? These fifth- and sixth-century monks (when the practice flourished) were serious guys, fearsomely so, but I could not help being amused by imagining them today: on telephone poles and cell phone towers, mystifying people, annoying cops, and drawing lawsuits. The other thing that struck me about them was their singleminded vision, largely divorced from the reality the rest of us inhabit. They were alone in their minds and with God.

When I first began writing about the pole-dwelling father of my story, I did it in the collective we of his children, who just want a normal dad and relief from his shenanigans. Then, as I continued to draft and explore the idea, the character of John emerged, the youngest son, who, alone among his siblings, embraces his father’s faith and fanaticism. Into John I poured some of my own confusion about faith and what constitutes a healthy life. Maxine’s appearance surprised and delighted me. Shrewdly pragmatic, she is the antithesis of the father, a folk hero of this world. Maxine illuminated for me the extent to which we are all playing games with ourselves in one form or another, as we seek to satisfy not only our baser cravings but our need for meaning and deeper fulfillment.