Welcome back to another dynamic performance of our double-interview feature Pax de Deux, this time between fiction writers and 11.1 contributors Joan Leegant and Leslie Parry (about whose story “Vogelsong” Brenda Peynado wrote a glowing appreciation last week). Scroll down to view the entrée of this two-part duet, in which the dancers brisé across such topics as the challenges of the first-person plural point of view, cabaret singing on a cruise ship, and water skiing elephants.

Joan Leegant: I was struck by your remarkable use—or maybe a better way to say it is deployment—of the multiple first-person. This went beyond merely telling the story in a plural voice so we’d know many people were involved; you also remained faithful to that multiple voice when describing individuals, as in this sentence: “We remembered later that it was a Monday because we missed our favorite radio program, or the weekly call from our sister, or the fish fry social at the church down the road, where we sometimes won a jar of marmalade in the raffle or got hopped-up with the townies behind the garage.” A less bold writer, concerned about mixing pronouns incorrectly, might have written something like: “We remembered that it was a Monday because one of us missed his favorite radio program and another of us missed the weekly call from her sister,” etc. The construction you chose appears several times in the story and works terrifically well to maintain the collective tone, which, in turn, works perfectly with the ending when all are understood to be complicit.

Joan Leegant: I was struck by your remarkable use—or maybe a better way to say it is deployment—of the multiple first-person. This went beyond merely telling the story in a plural voice so we’d know many people were involved; you also remained faithful to that multiple voice when describing individuals, as in this sentence: “We remembered later that it was a Monday because we missed our favorite radio program, or the weekly call from our sister, or the fish fry social at the church down the road, where we sometimes won a jar of marmalade in the raffle or got hopped-up with the townies behind the garage.” A less bold writer, concerned about mixing pronouns incorrectly, might have written something like: “We remembered that it was a Monday because one of us missed his favorite radio program and another of us missed the weekly call from her sister,” etc. The construction you chose appears several times in the story and works terrifically well to maintain the collective tone, which, in turn, works perfectly with the ending when all are understood to be complicit.

How did you come to use the multiple point of view as a way to tell the story? Was it there from the start? And how did your bold and unusual construction for describing individuals, while being faithful to the multiple voice, evolve?

Leslie Parry: This is one of the rare cases where I decided on the point of view before I began. I was interested in the cliquishness, camaraderie, and dysfunction that occurs when people live and work in the same place. (My sister was a cabaret singer on a cruise ship, and that dynamic—living in bunk beds, sailing around in a circle for eight months—always fascinated me. I was also interested in how quickly someone can tire of the novelty. Oh God, she would say, not Barbados again.) The Vogelsong performers collude in a daily illusion for their guests, which gives them a very specific bond: They know each other onstage and off, in the sun and in the shadow. But that lifestyle also means they have no real privacy, and the boundaries between them quickly disappear. I wanted to suggest that nobody has anything that’s truly her own anymore (even a radio program, or a telephone call), and because of that, nobody has any secrets either. Identities are merely superficial in a place like this. I kept a few individual distinctions, ones that might seem innocuous at first, but which carry greater weight as trust unravels and suspicions grow. I wanted to write about that blurring of selves, and what a person might cling to when she finds her individuality diminished. Where is the line between intimacy and complicity? When does loyalty give way to culpability? Is a secret worse when it is your burden alone, or when it binds you eternally to others?

JL: You create and sustain tension not simply by making the story about a boy who is lost but by giving the reader occasional glimpses into the shadow side of life there. Early on, we learn there are places the narrator(s) never tell the tourists about, that are left off the map—remnants of an old mural and an old slave cemetery. Later, we read about things the narrator(s) may have left out when reporting to the police early in the investigation—the diver being drunk, the alligator man flirting, the conquistador sneaking about with a young man and the scent of dope. These glimpses prepare us for the stunning ending, which begins: “But there was one thing we never told anybody.”

JL: You create and sustain tension not simply by making the story about a boy who is lost but by giving the reader occasional glimpses into the shadow side of life there. Early on, we learn there are places the narrator(s) never tell the tourists about, that are left off the map—remnants of an old mural and an old slave cemetery. Later, we read about things the narrator(s) may have left out when reporting to the police early in the investigation—the diver being drunk, the alligator man flirting, the conquistador sneaking about with a young man and the scent of dope. These glimpses prepare us for the stunning ending, which begins: “But there was one thing we never told anybody.”

In the course of writing the story, did the ending come to you first, after which you added those earlier intimations of the unspoken? Or did those earlier episodes lead you to the ending? Can you tell us about that?

LP: When I started writing, I knew how I wanted the story to end—maybe not the precise sentence or image, but the tone, the feeling of it. The narrators are bound and haunted by their unspoken secret. It unites them just as fully and perilously as it divides them. Their differences appear more trivial at the beginning: their tasks, their hometowns, their sexual inclinations. And with no chance to exercise a truly private life, and with every misstep and impulse already common knowledge, what could possibly remain unknown? And yet by the end, every small detail becomes a potentially loaded clue. So once I had written the ending, I went back and examined those quieter discrepancies, reaching back through time much in the way the characters did. What was the one thing they had taken for granted? What had they missed, or unwittingly allowed? Ultimately I felt it was better that I didn’t make a hard decision either—that I, as the writer, could speculate alongside the characters, but I could never know more than they did. It might have been any one of those things, or none of them. I can’t be sure myself.

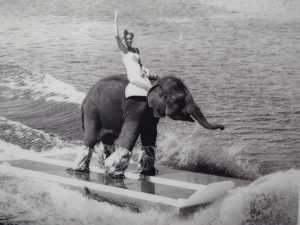

JL: Place is central to the story, and is beautiful and terrifying and primeval: nature trails, snakes, date palms, a lynching tree, German figurines of children in lederhosen. A black whoosh of birds, an alligator gnashing in its cage, a horse that can throw its rider, an enormous elephant. Ultimately, the place, and its inhabitants, devour the boy, and then it’s all torn down, vanished, though not in the dreams of the narrator(s).

JL: Place is central to the story, and is beautiful and terrifying and primeval: nature trails, snakes, date palms, a lynching tree, German figurines of children in lederhosen. A black whoosh of birds, an alligator gnashing in its cage, a horse that can throw its rider, an enormous elephant. Ultimately, the place, and its inhabitants, devour the boy, and then it’s all torn down, vanished, though not in the dreams of the narrator(s).

Were there particular challenges you faced in evoking that place? Did you worry about having too much detail, or visuals that might seem too freighted with symbolism? Did you have a sense of the place when you began the story, or did it evolve in the course of writing?

LP: I loved writing about Vogelsong. I based it (loosely) on a state park I visited in De Leon Springs, Florida. As soon as I set foot on the trail, with all of its wild beauty and eeriness, I knew I had a story. Then, when I learned a water-skiing elephant had once performed there, I knew I really had a story. The challenge was in making the setting (in all its iterations, from conquistador landing to plantation to amusement park) a real and necessary character, not just an interesting backdrop. It’s easy to get swept away with description and exposition, so I kept myself tethered by thinking of it this way: This particular story could only happen in this particular place. The details had to work on two levels: They had to set the stage and orient the reader; and they had to contribute to an underlying tension. They needed to convey both the wonder and artifice of this place, as well as the uneasy combination of inertia and mortality. Itemizing even the most mundane details—the map, the duties, the meals, the schedule—seemed gratuitous at first, but I found that it helped me to explore just how disorienting and dramatic a single aberration could be. I suppose, in a way, I was also writing about my greatest fear: getting away with something, and then having to live with it.