Divorce. The rate in the US, by some estimates, is 50 percent, but it seems like more. I mean, Al Gore and Tipper. Not to mention Deb and Gary, your high school friend’s really cool parents. And Gwyneth Paltrow and that guy from Coldplay? If they can’t make it, who can? As Louis C. K. says, “Marriage is just a larvae stage for true happiness, which is divorce.” He says that because he is . . . yep . . . divorced. Everyone, it seems, is either divorced or getting married so they can get divorced. So why try? Why tie the knot in the first place?

Divorce. The rate in the US, by some estimates, is 50 percent, but it seems like more. I mean, Al Gore and Tipper. Not to mention Deb and Gary, your high school friend’s really cool parents. And Gwyneth Paltrow and that guy from Coldplay? If they can’t make it, who can? As Louis C. K. says, “Marriage is just a larvae stage for true happiness, which is divorce.” He says that because he is . . . yep . . . divorced. Everyone, it seems, is either divorced or getting married so they can get divorced. So why try? Why tie the knot in the first place?

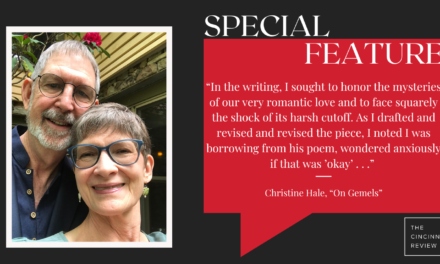

For one, you crazy kids, it might just work out. And for two, you might get some fantastic poems and stories out of it, like our four contributors in CR 10.2, who find inspiration in this ancient institution. Emma Duffy-Comparone addresses whether there is marriage through our many reincarnated lives, if you have a soul mate as a fish or a birch tree. Bruce Beasley ponders the intersection of marriage and atmospheric disturbance (hint: wind is divorce). Kevin Clark found his poem in the juxtaposition of an Italian Renaissance painting and the story of a marital love life gone stale. And Maureen Seaton looks at her daughter’s marriage for proof that her generation’s idealism has not gone to waste.

Bruce Beasley (on his poem “On Marriage”): During a period of several weddings of couples close to me, set alongside divorces of several other couples at the same time, I started thinking of marriage as a balance of desire and satiation, stability and restlessness for change. During a windstorm I started mulling the fact that what we call “wind” is nothing but air driven by changing atmospheric conditions into motion. I thought “divorce is to marriage as wind is to air”: an unexpected turbulence that disrupts or destroys. The inverse, though, also seemed true: marriage as a contained turbulence of desire. In thinking about the weddings and the divorces (and a divorce followed quickly by a marriage) I thought about the word immotive, which means “unmoving, immovable,” but sounds a great deal like emotive, which means “moved.” Marriage, then, as a mixture of the emotive and the immotive, the moving and the unmoveable. Marriage as a mixture of stasis and change, the restlessness of desire and the stability of devotion. I went looking for oxymoronic words and phrases—“hold fast” suggesting both stillness and speed; “still” containing both incompletion and change on the one hand (still going on) and motionlessness and stasis on the other (stillbirth) to suggest the paradoxical nature of marriage as a stillness amid the perturbations of change.

Emma Duffy-Comparone (on her story “Crossing the Sagamore”): I watched a Ted Talk once about how mushrooms can save the world: something about how they can clean up our most brutal waste, our oil spills, and our nuclear meltdowns. After learning this I went nuts, cooking with them almost every night. I think the affair lasted about a week, and then I called it off. But then I kept dreaming that I had beautiful gills down my ribs. I think these gills were more like a mushroom than a fish, but that made sense, too: my love for the ocean is so physical I’d have to call it lust, and I’ve always known on some level that I’ve lived in there. I mean, I just know I was a fish. And then, partly related to this issue is the question of whether there is a soul mate, one you keep bumping into whether you’re tuna together or birch trees on the side of the highway or soldiers in the Civil War, etc. I’m not sure if I believe it, but Deirdre and Ted seemed to, and then I sent Ted away. And in the meantime I gave those mushrooms a lot of work to do.

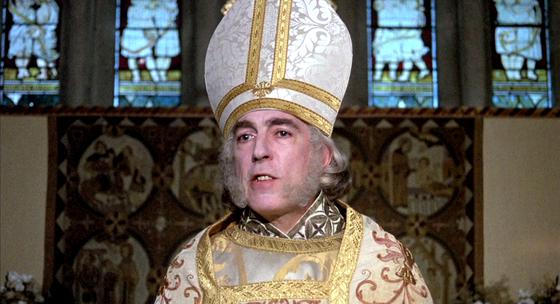

Kevin Clark (on his poem “Watching Kira Learn to Surf”): The poem emerged out of the longest sequence I’ve ever attempted. I’d known a long-married woman decades ago who broke up with her husband because he had no imagination in bed. Year after year, same thing in the same order, no matter what, she said. I’m sure that wasn’t the only problem, but I’d carried the idea of such a circumstance around in the back of my mind until I thought to myself, hey, that could be a dramatic subject for a poem. The effort led to the idea for a verse novel I’m calling Magdalene in Ecstasy, after a Renaissance painting by Sigismondo Coccapani. I want each poem to stand on its own, much in the manner of Andrew Hudgins’s After the Lost War, even though my book is structured differently than his. Marie, the speaker of “Watching Kira Learn to Surf,” is the main character, though two others speak as well: her ex-husband Jesse, a Vietnam vet and surf shop owner suffering silently from PTSD, and a lonely Italian lit professor named Raffaele with whom she’d spent a memorable night in the Baja when they were both twenty. Kira is Marie and Jesse’s only child. The poem describes a key moment in which Marie is with Jesse when she realizes that she must eventually leave him. The three characters have experienced a mix of deeply erotic and spiritual longing on their way to hard-earned, barely certain self-reliance.

Maureen Seaton (on her poem “Skinny Dipping”): “Skinny Dipping” came along as one of those poems that slams into your brain, messes with it, and leaves by the back door. I’ve been trying ever since to figure out if I actually believe what I wrote. I want to. I want a practical idealism, not something my imagination cooked up to keep me in the poppy field. I wrote it at 7,500 feet above sea level in New Mexico, far from the farmland of upstate New York, observing my daughter and her husband as they went about their gentle lives: December 2012. I think it occurred to me that something luminous had indeed survived from those four sodden days, our small and large wars, our bare feet and poppies. That my father had been wrong, after all, and there was Mike’s and my kid and Diane and Morton’s kid to prove it. Look at them, I thought, and the poem crashed into me fiercely, like music at 3 a.m., Woodstock, turn of an epoch.