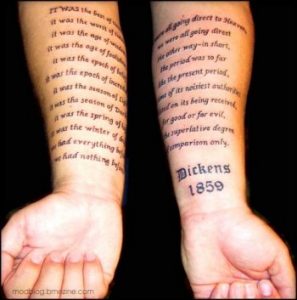

This week’s “Why We Like It” feature is a double whammy. It’s written by Becky Adnot, a long-time volunteer who is soon to join our staff (fall 2011); so this is also a “Why We Like Her” feature. For one thing, Becky has read submissions going on three years now—purely for the love of it. She hasn’t even demanded payment in pizza or Pabst, the grad students’ stock-in-trade. True, she has tried to eat some of her favorite passages from incoming manuscripts, but with love, dedication, and strategic use of a stun gun, we broke her of the habit. Now she merely holds the paper in her mouth until the ink transfers to her tongue, then sinks deeper into her membranes, the words becoming part of her. She refers to this process as “lit-spit-sorption.” Occasionally the words reemerge as watery tattoos here and there on Becky’s body, reorganizing themselves, rising to the surface, then drifting back into her dermal tissue to form new configurations. The following was transcribed from Becky’s shin and left kneecap.

This week’s “Why We Like It” feature is a double whammy. It’s written by Becky Adnot, a long-time volunteer who is soon to join our staff (fall 2011); so this is also a “Why We Like Her” feature. For one thing, Becky has read submissions going on three years now—purely for the love of it. She hasn’t even demanded payment in pizza or Pabst, the grad students’ stock-in-trade. True, she has tried to eat some of her favorite passages from incoming manuscripts, but with love, dedication, and strategic use of a stun gun, we broke her of the habit. Now she merely holds the paper in her mouth until the ink transfers to her tongue, then sinks deeper into her membranes, the words becoming part of her. She refers to this process as “lit-spit-sorption.” Occasionally the words reemerge as watery tattoos here and there on Becky’s body, reorganizing themselves, rising to the surface, then drifting back into her dermal tissue to form new configurations. The following was transcribed from Becky’s shin and left kneecap.

Becky Adnot: Jenn Scott’s “Myths of the Body” (5.1) begins with the discovery of a sex book in a men’s restroom. It ends with the discovery of two women, naked, under a blanket in the lounge of a fast-food restaurant, surrounded by a rumple of trash, the by-products of thievery and waste. In between, there are many more discoveries to be made. This is a story about Ana, the twenty-two-year-old assistant manager of a restaurant where the weekend cooks bread and fry their arms, where the green beans are canned and gray, where her boss—straight-laced and unappetizing—is also her boyfriend. As she passes through the prism of the ordinary, Ana discovers that her mother, who brings home a string of unsavory men, enjoys being called a slut. She discovers that Hipster Jesus, the frail, dirty boy who appears regularly at her register, is not her salvation.

The pleasures of Scott’s story are many: a diamond-sharp wit, prose as honest as it is gorgeous, characters that entertain and entice even as they remind us of the despondency of their situations. But the story’s greatest triumph may be the way that Scott asks the reader, politely, if he or she might choose to root for Ana. And we do: we cheer her as she steals her boyfriend’s wallet, as she batter-dips filched fish, as she renounces her managerial duties to eat pineapple cream cheese pie. Reading “Myths of the Body,” I was moved as often as I laughed out loud, often at the same time.