by José Angel Araguz

“The memory does not exist, you have to create them” (Jürgen Becker)

These words, with their implication of memory as mortal creation, are emblematic of the spirit behind the shorter poems of Jürgen Becker. Reading through Okla Elliott’s translation of Becker’s poems, I was struck by the importance and emphasis placed on everyday occurrences as material for such memory-making. In “Beginning of September,” for example, nuanced observations become vivid actions:

No war. The old woman

draws her head in, because

she hears an apple

crashing through the branches.

Here, Becker’s lyric works both like a diary and a dispatch from the frontlines of everyday life. The juxtaposition of the statement “No war” against the scene that follows evokes the tension of life during war, and how a residual tension exists after.

Becker’s speaker in this and other poems speaks in a personal and direct manner; this approach makes for lyrics able to evoke life with an immediacy similar to Japanese tanka. This immediacy is evident in the poem “What You See”:

The headlights turn briefly

through the curve, and for seconds

the room is bright. Then you see,

on the wall, the shadow of the tree

which stands barren this summer.

Here, the lyric places the reader in the moment not just of noticing but of realization. The pacing of images as well as the resonance developed through pacing and concision bring to mind Octavio Paz’s short lyrics. Where Paz’s emphasis was on the unfolding poem as a mirror to the unfolding self, Becker’s poems emphasize the unfolding moment as possibility for art. As the speaker of “Hell, Sartre Said, Is Other People” states about the “do-it-yourself handyman who makes the mood/for his and my evening” and his drilling into walls late in the day:

. . . In case I see him, I’ll, I’ll

do nothing. Like always, complaints go

in the poem, which makes a large staying noise.

This creation of “a large staying noise” is exactly the ambition behind these poems. For Becker, the material to make this noise comes directly from memory. Through poetry, memories can be created from what we do and do not see, thus clarifying and pointing toward both what does and does not exist. When the poem “Tenth of July” moves from the image of gorse on a postcard into a memory of gorse not being there, an indirect presence is created around the idea of the shrub:

Gorse; with a postcard

from Elba island gorse comes

into the house; it’s Proust’s birthday;

and the memory of gorse

in those years when, along the railway,

the gorse didn’t bloom.

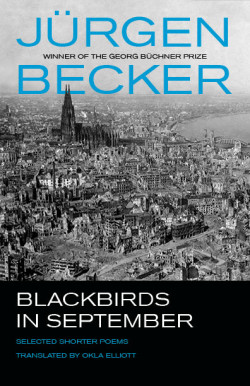

“The decision to focus on [Becker’s] shorter poems,” Elliott shared via email, “was a practical one. He has such a large body of work, and he has done so many longer poems (5 to 50 pages in length) that to simply choose one or two to represent that entire vein of his output seemed like too much of a disservice. His longer poems also have quite a different flavor than his shorter ones, so the two types of poems didn’t seem to live together in a single book very well. I plan to tackle a selection of his longer poems in the future to create a companion volume to Blackbirds in September.”

“The decision to focus on [Becker’s] shorter poems,” Elliott shared via email, “was a practical one. He has such a large body of work, and he has done so many longer poems (5 to 50 pages in length) that to simply choose one or two to represent that entire vein of his output seemed like too much of a disservice. His longer poems also have quite a different flavor than his shorter ones, so the two types of poems didn’t seem to live together in a single book very well. I plan to tackle a selection of his longer poems in the future to create a companion volume to Blackbirds in September.”

When asked what influence translating Becker’s poems has had on him, on or off the page, Elliott said:

“Interestingly, Cincinnati Review just published a poem of mine that I consider very much influenced by the lyric logic of Becker’s poems. I think that’s what I learned most from translating his work, his subterranean and unspoken logic. In order to translate someone, you have to become a linguistic mimic of sorts, and by taking on his voice I learned to think like him a bit. Becker will likely forever be an influence on my poetry, even if only in subtle ways that are undetectable in terms of content or phrasing.”

Check out Okla Elliott’s poem “Machine-Minded” in issue 12.2 of The Cincinnati Review.

Blackbirds in September is available for purchase from Black Lawrence Press.