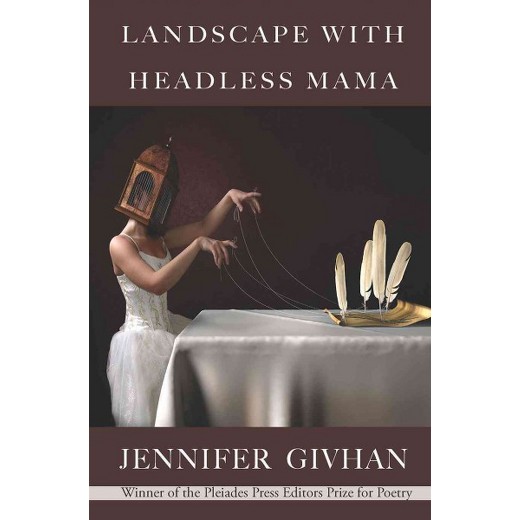

In “Rummage,” midway through CR contributor Jennifer Givhan’s Landscape with Headless Mama (Pleiades Press), the reader is presented a scene of a yard sale; the opening image of a wedding dress as “a white tumble / alongside registry gifts rattling our tarpaulined front porch” sets the tone. As the speaker details the scene, we learn:

In “Rummage,” midway through CR contributor Jennifer Givhan’s Landscape with Headless Mama (Pleiades Press), the reader is presented a scene of a yard sale; the opening image of a wedding dress as “a white tumble / alongside registry gifts rattling our tarpaulined front porch” sets the tone. As the speaker details the scene, we learn:

You’ve lost your job as I’ve lost

my faith, selling all our things:

our marriage, our love, the birth

certificates of our imagined ones. How much?

is the only question I can answer.

The connotations of a yard sale, of putting personal belongings for sale on display where one lives, are amplified by the speaker’s monologue, establishing this public act as one born out of loss and need. This layering of meaning via a distinct sensibility for image, voice, and rhetoric presents what is at stake in a clear and compelling manner. When the reader gets to “the only question” the speaker can answer, that question “How much?” is given an emotional torque that evokes how everyday public conversation is often edged with the personal.

Throughout the collection’s poems that engage with narratives of motherhood, family, adoption, love, and culture, Givhan works out various answers to this question of “How much?” which reaches after the cost of things. The poem “Prayer for the Child I Keep Losing,” delves into how much it costs to lose a child:

She’s curling at the edges—

she’s steam from smokestacks unused for ages

yet curing each winter

& finding breath

miraculous against the cold.

Here, the imagery shifts from “steam from smokestacks unused for ages” to the steam of human breath. This transformation implies a restlessness, a further “losing” of the child played out in lyric observation. Yet, holding is also implied; as the poem develops its images that pass into each other, each line holds a sense of loss and presence. That the poem is titled a prayer brings us back to the public/personal dynamic; this personal expression of loss is made in a public space, the poem. What is present, then, in the poem is the tension that makes lyric poetry compelling. The question of how much is answered by the poem’s closing lines:

She’s a light I cannot see

at the edges of every rising, &, oh, every falling thing.

This final image drives home the situation of the speaker, one of finding reminders of the loss and reasons to pray all around her, and, thus, always having to interpret the personal through public, exterior means. This motion at the end of “rising” and “falling” leaves the speaker back at restlessness, but a restlessness sought after and explored.

This impulse for seeking and exploring finds expression in both lyric and formal innovation: “Chicken-Hearted” subverts the sestina, and “A Crown for Headless Mama in Her 14×14 Music Box” presents a crown of sonnets. This latter sequence allows for the full range of the collection’s narratives to meet, the speaker going through many roles as mother, daughter, wife, woman, artist, and poet-storyteller. From this multiplicity, a current of possibility arises; through juxtaposition and voice, the reader is swept up into the worlds of the book. In the second sonnet of this crown, the following dream is evoked:

In a museum, once, we were trapped like frost

on the windowsill when they dimmed the lights

& the monkey-woven Kahlos began

scuttling from their walls toward my babies &

me, demanding I choose. The chirping

smoke alarm woke me, no longer able

to dream us back together. Still the art

kept repeating we’re alive, we’re alive.

This repeated phrase runs counter to the question of how much things cost, making it clear that it isn’t the cost, ultimately, that matters, but that one is alive and able to ask the question and that the presence of art will answer it.

interview

JAA: What were the challenges in writing these poems and how did you work through them?

JG: Poetry is tough, it spits pulp, it is cactus spines, it carries water in its belly. Slices of Landscape with Headless Mama were written through a mental breakdown when I feared seriously for my life and my children’s lives. I pulled trauma from the breaking points & stoppered the cracks with flowers, with chicle on the roadside, with inky love. Poetry does that for me, the hard & gorgeous, harrowing & mending poems I read of others & the poems the Muse brings me.

JG: Poetry is tough, it spits pulp, it is cactus spines, it carries water in its belly. Slices of Landscape with Headless Mama were written through a mental breakdown when I feared seriously for my life and my children’s lives. I pulled trauma from the breaking points & stoppered the cracks with flowers, with chicle on the roadside, with inky love. Poetry does that for me, the hard & gorgeous, harrowing & mending poems I read of others & the poems the Muse brings me.

The challenge is how to dwell in darkness searching for light without succumbing to either. Finding unstable truths & rendering them on the page without flattening them. Keeping their luminescence & their shadow stains. It’s easy to say this thing is done. My heart is glad. I will rejoice. Sometimes it’s even easy to mean it.

When the pain returns—cyclical as genetics—what then?

I pulled poems from earlier drafts of the collection & rewrote what clung like berries to a windstormed tree, a hundred times, no exaggeration. I sang these songs until I knew them by heart & then I changed my heart. I laid them on the ground & watched them root themselves to the floor or each other & then I pulled them like weeds & sheared their flowerfisted heads. I was relentless. Because poems are tough. They make me tough. & I tried hard only to take into myself & by myself I mean Headless Mama that which made me stronger.

In my MFA program I heard all kinds of voices. Most of them I had to silence. Most of all I had to watch the paintings swirl. Most of all I had to turn up the music & dance. & there were some voices that danced inside me & those I cultivated, for those I rejoiced. If this sounds strange it is but poetry is strange. & again & again & again have faith.

Poetry is faith. This book is my first as my first child as any first heartswell & reminds me of what is possible.

*

Landsape With Headless Mama is available for purchase from Pleiades Press.

To find out more about Jennifer Givhan’s work, check out her site. We look forward to featuring two of her poems in our upcoming issue, due out in mid-June.