Don Peteroy: In Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, the narrator says “So it goes” 106 times. It’s a sigh; it conveys melancholy, and always appears after something—animate or inanimate—moves on. Similarly, throughout Stephen King’s series The Dark Tower, the narrators and characters say “The world has moved on” too many times for me to count.

Don Peteroy: In Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, the narrator says “So it goes” 106 times. It’s a sigh; it conveys melancholy, and always appears after something—animate or inanimate—moves on. Similarly, throughout Stephen King’s series The Dark Tower, the narrators and characters say “The world has moved on” too many times for me to count.

Here at Cincinnati Review, though 12.1 is now available, our world has not . . . yet . . . moved on. Back issues of CR 11.2 are still available for order, and we have some wonderful comments from contributors in that issue, discussing their pieces, their struggles, their inspirations. The three writers below attest to what can be done when the world insists it must move on.

Dan Bellm: In the days and weeks after my mother’s death in 2010, at the end of a very long good-bye, her very long passage through Alzheimer’s disease, there was practically nothing at all that I could bear reading, and I am a constant reader. Certainly not any kind of poetry of “consolation.” You might say by chance I ended up pulling Basho’s Narrow Road to the Deep North off a shelf, that great prose-and-poem account of a long journey on foot in seventh century Japan that had nothing and everything to do with my present experience and state of mind. I can’t entirely say, but something of its air of peace and acceptance, of transience and eternity, stayed with me. My notebook started filling up with fairly bad attempts at haiku, brief gestures that almost never cohered. This was somehow all right. Eventually I stayed with nothing of that “form” except for what is probably its least important element, the syllables, the tercet of five and seven and five. For a good long while, until it ended, this became the way I thought and wrote; it gave me a vessel in which to address, remember, and try to evoke my mother. As many writers before me have said, I found freedom in the constraint. The two pieces in Cincinnati Review both come near the end of the book-length elegy for my mother that is also called Deep Well, entirely written in this syllabic form.

Katherine Karlin: Like many readers, I was deeply affected by David Sedaris’s account of the suicide of his sister, Tiffany. The debates that ensued afterwards—was Sedaris displaying an appropriate sense of grief? Was he sufficiently honoring the deceased?—discounted an inevitable premise: this was David’s story, not Tiffany’s. He never presumed to represent her voice, nor should he. Still, I was unnerved by her silence and began to explore through fictive imagination (the only way I know how) what it might be like to nurse a dogged mental illness when you come from an accomplished, hyper-verbal family. In my story, Honey is tragic not only because her mind works in reflexive circuits she can’t escape but also because, like all suicides, she cedes the last word of her own narrative.

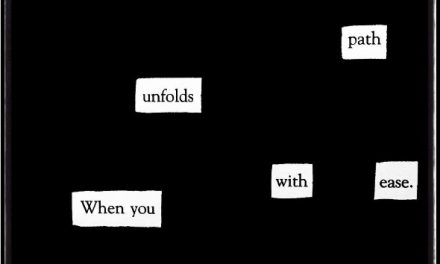

Claudia Monpere: “The Now” is part of a manuscript called Person in Water about my husband’s suicide. I wrote fiercely in a notebook for about a year after his death, never complete poems but questions, images, rants, summaries of his last days, disembodied lines that much later entered some poems. I wrote “The Now” a few years after his death, trying to create the intensity of that week when I had trouble breathing and the days were a rush of family and police flooding my house and memories and images clashing with one another. I worried that my dad would fall in the rain on the path to my front door, remembered paintings in an art gallery on a trip when my husband was stable and happy, felt terror for my children’s future, obsessed about the cause of his suicide. I struggled with the poem’s form, but once I figured it out, the lines came fairly quickly