Yep, it’s time (some would say high time) for associate editor Don Peteroy to lob another Irrelevant Question at an Unsuspecting Writer. Actually, we always clear the question with the writer beforehand. Actually, sometimes the writer doesn’t like the question and asks for another. Actually, sometimes the writer never responds, which is, we guess, another way of indicating he or she didn’t like the question. Which all goes toward saying we never know how a writer is going to respond. That’s the cool part. The recipient of this edition’s Irrelevant Question—Colin Fleming—really delivered. We don’t know about you folks, but here at CR we’ve been longing for a good, rousing disquisition. Something we can stand back and let unfold, and unfold, and then say, simply, “Wow.” A disquisition that tackles a difficult distinction, such as the difference between good writing and writerly writing. (The latter term designating writing that is meant to sound good, often isn’t, but fools people anyway.) Feeling brave? Read on.

Question: It’s about time we have some fresh new literary terms, don’t you agree? Could you please coin some new terms, and define them?

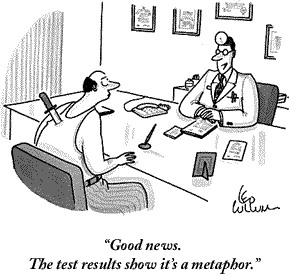

CF: As someone who can’t read a book, no matter what it is, without marking it up and writing in the margins, I’ve come to realize that I’ve done this sort of thing where I’ve blended literary terms into my thinking such that I’ve done away with, you know, terminess. I’ve stopped pausing to label something as some form of device. I want to get beyond that and see something m ore integrated, so I’m always in the sentence, not in the label. If you see a metaphor as more than metaphor, you’re never leaving the sentence, and the author is doing a bang-up job by keeping you there.

ore integrated, so I’m always in the sentence, not in the label. If you see a metaphor as more than metaphor, you’re never leaving the sentence, and the author is doing a bang-up job by keeping you there.

And since I wonder, too, who really knows more than a few literary terms these days, it seems we could use a few that go beyond academic speak. I like the stuff that registers with the people across the hall, and that’s what tends to register most with me.

I read so much material full of what I call moves. Term the first! I hate moves. A move is when a writer is doing one of these “Look at me, Ma, I’m really writing!” deals. A lot of literary magazines love moves. They like stories written in the monotone third person, with sentences that remind me of someone slamming back a typewriter carriage at the end of a line and starting again. The perpetual da-dat-da-dat-da-dat (repeat, repeat, repeat) sentence structure of so much contemporary fiction. Moves are viewed as literary, as not how the “rabble” would ever express anything, thus conferring an imagined superiority on the writer. Pens are not waved through the air. They are wanded. Move. I looked at this one book where a line went something like “The sun gentles the wall of the building across the street.” It gentles it? It fucking gentles it? Move Central. Don’t do moves. You know when you’re doing a move. Moves are for your insecurity, and if someone is doing them past their juvenilia period, there ain’t a lot of talent there. Which can be confusing, because there is a system in place to reward moves.

Move-buffs also tend to be what I think of as sandboxers. As in, playing in the sandbox with the cronies. A sandboxer is someone who writes and hopes rather than writes and knows: labors over some 300 word short-short for an age, and then requires a fellow sandboxer to praise it, and then a dozen others, so that it can be thought of as good. The original sandboxer is subsequently pressed to return this service for his confederates, perpetuating a cycle of codependency and enabling, which allows the sandboxer to replace actual reality with an invented one. Sandboxers spend huge amounts of time on social media, posting dozens of items a day that read like especially bromidic dross from literary fortune cookies. One will encounter things like “If I could be trapped in a bookstore 24/7, I’d happily be an agoraphobic #snuggles.”

A more cheery term, the one that matters most to me and that is crucial to writing—certainly writing that lasts—is a simple one: life. You know when you see life in something you read, because you feel it, and you exclaim, in a way, your way, “There it is!” I’d argue that the more life in something, the harder it is to get it into most journals, but that’s another matter. You can’t fake life—that moment that fifty different people encounter and connect with in a personal way, disparate though these people and their experiences are. The life moment is the “push away from the desk moment,” the “I think I’m going to go for a walk around the block or down by the harbor” moment, the great unshakable that comes back to you at different points, and differently each time. I find myself denoting this, of late, with “That is the stuff,” in the margins of what I’m reading. Life is a long way from the box. Which sounds like a double entendre, but isn’t. See? Old school lit term there amidst the new. Like a sponsor!

A more cheery term, the one that matters most to me and that is crucial to writing—certainly writing that lasts—is a simple one: life. You know when you see life in something you read, because you feel it, and you exclaim, in a way, your way, “There it is!” I’d argue that the more life in something, the harder it is to get it into most journals, but that’s another matter. You can’t fake life—that moment that fifty different people encounter and connect with in a personal way, disparate though these people and their experiences are. The life moment is the “push away from the desk moment,” the “I think I’m going to go for a walk around the block or down by the harbor” moment, the great unshakable that comes back to you at different points, and differently each time. I find myself denoting this, of late, with “That is the stuff,” in the margins of what I’m reading. Life is a long way from the box. Which sounds like a double entendre, but isn’t. See? Old school lit term there amidst the new. Like a sponsor!