The human skull—perhaps no artifact so powerfully represents ephemerality and longevity, vulnerability and strength, enlightenment and its concommitant darkness, apex and nadir, life and death. Its complex and conflicting associations have historically made the skull a powerful symbol in art, literature, mythology, and ritual, representing the unknown as well as the known. Meshell Ndegeocello has remarked, “I’ll never understand what makes our minds do the things we do. It’s like that statue of the monkey holding a skull. We’re trying to use a thing we don’t understand to understand ourselves.” In an evocative long sequence inspired by two ornamented skulls, Ashley Anna McHugh offers a richly contemplative exploration not just of the head, but of the heart.

Ashley Anna McHugh: My manuscript Descent unspools the mythology and beliefs of our earliest civilization in three interwoven poetic sequences to see what it has left us, and what lasts. In Descent, “The Red Hours” forms part of a sequence about prehistoric burial rites in the ancient Near East, and it was inspired by the archeological finds of skulls in Jericho (7000 b.c.)—and commonly across the Near East, actually—that were decorated to resemble fleshed human faces.

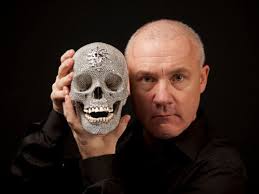

While considering what these finds might mean to us now, I came across Damien Hirst’s For The Love of God—a real human skull casted in platinum and encrusted with over eight thousand diamonds. Originally, in an early attempt at writing about these two skulls, I made a one-to-one comparison, but it eventually seemed to me like my poem wasn’t as good as the art it was about—a challenge that any ekphrastic poem must overcome.

While considering what these finds might mean to us now, I came across Damien Hirst’s For The Love of God—a real human skull casted in platinum and encrusted with over eight thousand diamonds. Originally, in an early attempt at writing about these two skulls, I made a one-to-one comparison, but it eventually seemed to me like my poem wasn’t as good as the art it was about—a challenge that any ekphrastic poem must overcome.

So I started from scratch. I studied and took notes about traditional historic interpretations of skulls and diamonds, and I tried to make connections; I wrote questions in my notebooks, though I had no answers. I copied out Hamlet’s speech to Horatio by hand, and I listened to Kanye West’s “Diamonds from Sierra Leone (Remix)” on loop for weeks while I wrote. In short, I tried to uncover why both of these skulls—the one from Jericho, the one created by Hirst—were meaningful to me, each in their own distinctly disturbing way.

In the end, what struck me about both skulls was how they each tried to overcome death, to remake death—through love, through beauty and wealth—and how they both failed. In “The Red Hours,” I wanted to capture the mind grasping for a rationalization, for a proof against death—and ultimately, finding nothing to hold. I wanted to illustrate both our intense longing to outlast death in some way, and the inevitability of the fact that we won’t.