Assistant Editor Holli Carrell: I first encountered Frank O’Hara’s poem “Ave Maria” as an undergraduate student many years ago. While I didn’t read much poetry then, I remember carefully writing O’Hara’s ode to cinema in my notebook. Having been raised in a religious environment where many films were forbidden, I adored O’Hara’s insistence on the virtue and importance of film on young people’s developing minds and imaginations. In my favorite lines, O’Hara suggests that our exposure to film—art—is transformative, cathartic, and even spiritual. He writes: “it’s true that fresh air is good for the body / but what about the / soul that grows in darkness, embossed by silvery images.” Inspired by these lines, this new Cincinnati Review film column, “Talking Pictures,” will pay tribute to the films that have moved, inspired, and transformed us.

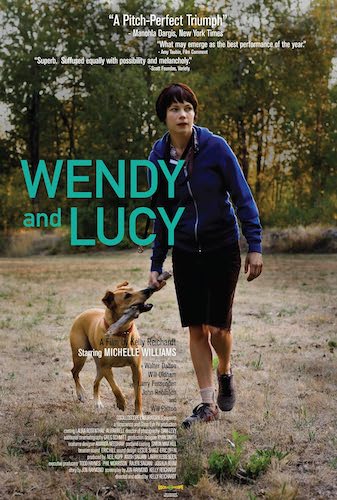

Released in 2008, in the middle of the Great Recession, Wendy and Lucy (dir. Kelly Reichardt) is a film about one person’s everyday struggle to survive within a society and economic model that values profit over humanity. Wendy and Lucy is also a tragedy: a love story about a woman named Wendy (Michelle Williams) and her dog, Lucy, the bond and love they share, and how forces beyond their control rupture it.

If you’re familiar with Reichardt’s films, you know she doesn’t fixate on backstory. Wendy and Lucy begins in medias res: a woman travels through Oregon with her dog in a dinged-up 1988 Honda Accord. Her journey began in Indiana, and her final destination is Alaska, where the need for seasonal workers at fisheries is abundant. We know little else about Wendy and watch her meticulously record her mileage and tally money spent on the road (hot dog: $1.50, trail mix: $3.00). She has few possessions, an injured ankle, no cellphone or credit card, and sleeps in her car in empty parking lots.

If you’re one of the 61% percent of Americans living paycheck to paycheck, or worse, you know how quickly shit can hit the fan. Wendy wakes up one morning in a Walgreens parking lot, and her car won’t start. They are stranded; the town’s auto mechanic is AWOL; Lucy is out of kibble, and cash is running out fast. Wendy counters her growing sense of helplessness by concentrating on her pet, but when she pockets two cans of dog food for Lucy in a supermarket, she is apprehended by a store clerk.

The following scenes are quietly agonizing: the young store clerk, a real asshole, goads his boss into phoning the cops. He argues that Wendy must be an example to other shoplifters, and “if a person can’t afford dog food, they shouldn’t have a dog.” Lucy is left in the store’s parking lot, fastened to a bike rack, as Wendy is hauled to the police station to be fingerprinted and booked. Wendy is detained in a jail cell for hours, consumed by overwhelming desperation for Lucy’s safety, as any pet owner can imagine. Lucy is gone when Wendy is finally released and sprints back to the store.

The myriad ways policing breaks lives and families in our country is not news, and Wendy, as a white woman—albeit unhoused—has privileges not afforded to everyone in similar circumstances. We see Wendy walk back and forth, calling for Lucy against the noisy, indifferent street traffic. Her terror is palpable and rises as day turns to night, and Lucy is still unfound. To say that Wendy is alone and vulnerable is an understatement. Her call to a family member for financial assistance is met with hostility, and once Wendy’s car is towed for the repairs she can hardly afford, she has nowhere safe to sleep. Alone at night, without her dog for added protection, she is powerless against violence and assault, which we glimpse in one terrifying scene.

If I’ve learned anything in my thirty-five years, it is that sometimes we are briefly bestowed with immeasurable luck and that luck is frequently granted to us in the form of a person, a friend. Amid the chaos of the situation, Wendy develops a rapport with an elderly Walgreens security guard (Walter Dalton) who works twelve-hour shifts patrolling the parking lot. Unlike the store clerk, high on a dose of cutthroat capitalism, the security guard cares about Wendy and is genuinely concerned for her. He comforts and reassures Wendy that Lucy will be found, acts as a liaison between Wendy and the pound because she has no cell phone, and gives Wendy the little spare money he has (six dollars). Their amicable conversation often centers on how the system is “fixed” and unnavigable.

On the same morning that Wendy discovers that Lucy has been found and is safe in a foster home, she is informed that her car is practically totaled, and the necessary repairs are beyond her financial reach. The mechanic insists the car is “taking up space” and can’t be left “sitting out there.” He offers to “junk” Wendy’s car for thirty dollars because “it’s got to go.” Room must be made for other customers, the engine of commerce and profit uninterrupted by those who can’t keep up with the system. Wendy is given very little time to consider her options, and the reality is that she has very few available to her. She must walk away from the little security and shelter she once had.

In the film’s final scenes, Wendy uses her remaining cash to take a cab across town to retrieve Lucy. She approaches the home and sees Lucy resting in a modest, fenced-in yard. The reunion is filled with excitement, play, and sorrow, and the spoiler that I won’t draw out here is that Wendy eventually leaves Lucy in the foster’s yard and walks away sobbing. Reichardt implies that Wendy walks away because she is confident that Lucy will be cared for, and perhaps this is because the foster, an older man, is reminiscent of Wendy’s friend, the security guard. But a lawn and property can never guarantee an animal’s security and safekeeping. What I find so upsetting about this scene, and what makes it successful, is my sense that Wendy leaves Lucy not only because she selflessly wants what may be “best” for her pet but because she has internalized the belief that her poverty disqualifies her from having a pet, a companion, and love. Wendy tells Lucy they will be together again when she “makes(s) some money.” In the final scene, Wendy hops the back of a freight train, her labor and body a commodity shipped across state lines. She holds herself against the passing landscape and shadows.

It’s been fifteen years since the release of Wendy and Lucy, and as I watch the film, it seems that everything has changed, and nothing has changed. The technology in the film is unrecognizable; the absence of smartphones is jarring. And yet, forty-two iPhone models later, the inability to earn a livable wage and affordable housing remains unchanged and unreachable for so many individuals and families. Wendy and Lucy is a quiet and unflinching reminder of the commonalities that draw us together despite our differences: the shared, urgent need to provide for ourselves and those we love most in this world.