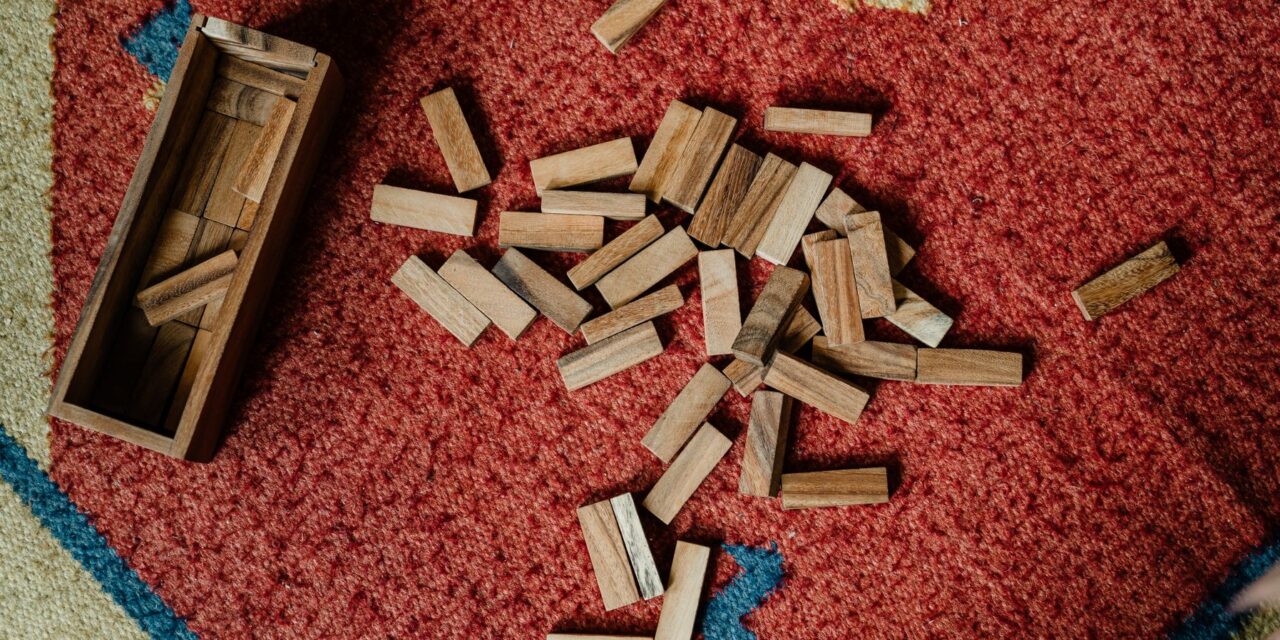

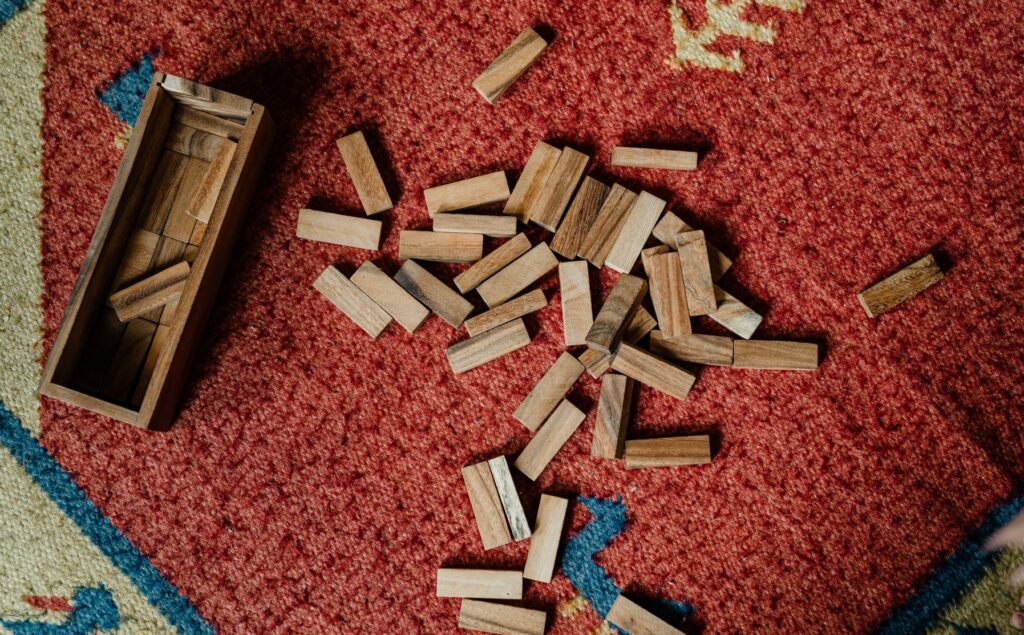

Associate Editor Madeleine Wattenberg: Thinking about when poems are ready to send out for some reason causes the game Jenga to pop into my mind. When playing Jenga, there comes a turn where no piece can be removed without causing all the pieces to fall. Every piece remaining is necessary regardless of where it’s placed in the whole. One more move and the whole structure topples. Submit!

This can be a difficult point to determine. You have to tap and wiggle each comma, each line break, to see if it’s willing to move. Try out synonyms. Move a line up or down. Sometimes you don’t know a piece is necessary until you’ve removed it and suddenly all your words look like disconnected pieces lying on the table.

The good news is that if you do knock everything down, you can edit your way into a new poem. Every choice leads to a different structure, a different tipping point, and often we don’t know we’re there until the whole structure is wobbling with potential before our mind’s fingertips.

Though the above metaphor doesn’t work for every poet (maybe you aren’t interested in that wobbly Jenga moment at all), it offers a pretty conventional take, one that sees revision as a linear process of winnowing and removing. Perhaps you prefer to offer the aftermath, the disordered pile-up of what was, the excess of pieces haphazardly scattered now on the table. Perhaps you use your wooden blocks to build houses. Maybe you dislike Jenga. These can also be poems.

A different way to think about this question is not how to know when your poem is ready, but, as Michael Chang suggests, what your poem is doing. What does it mean to have this version of your poem published? Who are you playing with and why?

It turns out that if you ask a poet about how to know when a poem is ready to submit, they’re going to want to offer a definition of poetry to go with it. In order to gather a wider range of perspectives, I reached out to some Cincinnati Review contributors about when it’s time to gather your work and hit “submit.”

Brian Brodeur, from Issue 17.1: For years, I’ve been trying to break the troublesome habit of submitting poems too soon. Was it Horace who advised young writers to wait nine years after “finishing” a piece before even thinking about publishing? Nine years seems steep, especially if one has, or is attempting to get, a tenure-track job. Still, a certain “cooling time,” as C. D. Wright phrases it, is essential to understanding not only whether a poem is “ready” but if it’s even a poem at all.

My practice is to write, revise, and share a new poem with one or two trusted writer/artist friends, then to revise again before moving on to another poem. Usually, if I feel stuck, starting afresh will teach me how to work through whatever technical problem was hindering an older poem–essentially teaching me, as Frost observed in a slightly different context, to remember something I didn’t know I knew. Then I try to put the poem away for a few months, then to revisit it once I’ve more or less forgotten it. If the poem still seems fresh, I’ll send it out. If not, I’ll stash it with the other failed attempts.

Michael Chang, from Issue 17.2: Sure, you can loll something about, swish it around in your mouth, but if you’re being honest you know in the first few seconds whether you like the taste of it.

Poems for me capture the essence of a moment, and when a moment passes, it can never be recaptured.

In that way, a poem is at its most inviting, magnetic, when it is first complete.

I think it’s critical to write towards your obsessions, lean into your impulses, be faithful to your broader writing mission (why you are in this poetry game when there are a million easier things).

I don’t believe in heavy revision; I think cosmetic changes, little nips and tucks go a long way. It isn’t constructive to think about whether a poem is “ready”—it is more important to examine whether it meets the moment, whether it accomplishes what you set out to do.

Satya Dash, from miCRo: Paul Valéry’s words, “a poem is never finished, only abandoned” rings true especially when one is submitting, but for me the real question after rounds of revision is: are you, as the poet, saturated at this instant, with your poem? Has the poem reached, according to the “now” you, its optimal tint of surprise/delight/terror in the discovery of landing lines on the page? If no, there is some distance to cover. A round of revision after some time away from the poem helps you look at your own creation with fresher eyes. I love the resolve of what Jamaal May says: “I edit until every line feels memorable to me.”

Of course it happens on many occasions that I rework submitted poems when I view them later, because as a writer my perceptions of saturation and hues are changing all the time. I allow myself that margin of parallax error— which I think is a component of the poem’s mystique and a reason why that version could only be written by a person having at that instant exactly the same interior world as yours.

Based on these responses, here are two questions to ask yourself before you submit:

- Instead of asking if the poem is ready, ask: what will it do?

- Does your poem delight you at every instance?

And some practical advice:

- Put your poem in a drawer OR submit it before you lose your sense of the moment

- Share the poem with trusted friends

- Write the poem from memory without looking at old drafts to see what holds

- Your first draft may be the best draft—editing doesn’t always mean improving

Finally, it’s also worth noting that publishing your poem in a literary journal is different from publishing it in a book. At the Cincinnati Review, we have a firm policy of not accepting revisions after acceptance; we like the poem we accepted. But, as Satya suggests, writers shouldn’t feel that this means their poem cannot later be revised—that we are the end of the poem’s life cycle. Publication may just be an imprint—a fossil—of a poem going elsewhere.