Assistant Editor Maggie Su: Let’s start by saying that it’s difficult to define very short prose. In the process of writing this post, I came across many well-meaning flash-fiction “Do and Don’t” lists all of which managed, without fail, to piss me off. As a teacher, I’m well aware that this is a common reaction to creative writing maxims. My students resist when I try to remove their abstractions and clichés. They insist that the “It was all a dream” twist ending can still work. They don’t understand why introducing ten characters on the first page is a faux pas. The truth is that writers don’t like being told what to do—we’re taught that fiction can be anything, and to place limits on the imagination feels almost sacrilegious.

Yet microfiction is tricky to learn precisely because it both relies on and resists rules. On one hand, it’s characterized by its arbitrary word count: 1000 words for flash fiction pieces, 500 words for micro or short shorts. On the other hand, it’s a form defined by hybridity, an elusive middle space that resists being pinned down by internet listicles. My professor Jacinda Townsend once told me that novels span decades, short stories last weeks, but microfictions are concerned with eternity. Microfictions inhabit a timeless conceptual space—a gap between poetry and longer prose that bends the rules of traditional genre conventions.

You might be thinking, “That’s fine, but how do you write something that occupies a timeless conceptual space?” to which I might answer, “In an unimaginable number of different ways.” Is that helpful?

What I can speak to is the time I’ve spent working on our award-winning miCRo series, where we’ve been lucky enough to publish micros which stretch the limits of what very short fiction can do. One such story is Julie Jones’s “Well Done, Middle School Administrators”—a dreamscape in which a bear chases the narrator and his father through his middle school. In the second paragraph, the narrator gains magnetic power, reaches into a girl’s backpack, and grabs a gun. This turn debunks the myth that very short fictions can’t contain plot complications and must rely solely on images to create momentum. In the absurdist style of Donald Barthleme, Jones’s shifting premise launches the reader down the rabbit hole without hesitation.

Similarly ambitious is Harrison Geosits’s “Three Filipinas,” a three-hundered-word nonfiction piece, which spans decades of three sisters’ lives. He writes, “1. They are born and raised in monsoon season, brushing humidity through their raven hair like all the other island girls do.” By using a numbered list, Geosits creates tension between form and content—the list implies easy categorization, yet the sisters’ paths reveal the false simplicity of the “American dream.” Through its sweeping macro scope, Geosits piece subverts the popular idea that short prose must limit itself to slice of life sketches or micro snapshots.

In the end, very short prose is a genre that embraces contradiction, where even the name “flash fiction” is a misnomer. Merriam-Webster defines the phrase “flash in the pan” as “a sudden spasmodic effort that accomplishes nothing.” By contrast, great flash fiction is that which lingers and changes the reader. Very short prose has the potential to give you eternity in less than five hundred words.

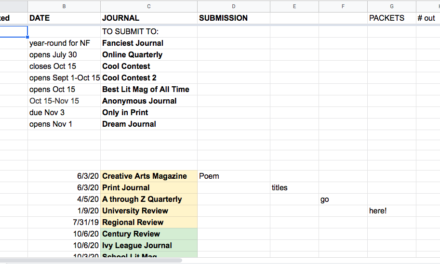

You can submit to our miCRo series here. These submissions are read by our team of assistant editors with an expedited turnaround time of four to six weeks. Break the rules. Surprise us with something we haven’t seen before.

For more miCRo pieces, CLICK HERE