Editors’ note: Because our reading process plays out over months, by the time we came across Kevin McIlvoy’s story in our submission queue this fall, it was after his unexpected death in late September. We wrote to his wife, Christine Hale, saying that we wished we would have been able to get to it sooner and that we’d love to present it as a special feature on our site. She agreed and suggested that Kevin’s good friend Sebastian Matthews would be the right person to write a short introduction. We’re honored to present this piece, which portrays the interior life of an artist and the challenges of getting art “right.” We have added white space to account for how each section would have started on a new page in print. See the bottom of this post for information about a memorial celebration for Kevin on Nov. 29.

Six Things I’d Like to Convey to You Before You Read Kevin McIlvoy’s “Six Portraits”

Sebastian Matthews: When you first come upon a Kevin McIlvoy story, you may find yourself thinking, This work is deeply strange. And you’d be right: it is deeply strange. Though by “strange” I mean wondrous, wild, a little manic, utterly original.

*

In an interview I conducted with Mc last year, he explored his idea of wildness:

As I compose and revise the opening pages of a novel, I’m always asking that the work’s full wildness provoke and invite the reader whom I imagine as a reader wishing to be lost, not found, wishing to be vulnerable, not in control. After all, a reader can always find in life the paths into being tamed. Why shouldn’t a novelist, who has been led by the work into inescapable wildness, share the journey?

*

Mc’s mind is one of the most brilliant and imaginative I have ever encountered.

*

In one of his Warren Wilson College MFA lectures—also deeply strange—Mc wrote: “It has been my practice to place my first trust in the human voice.” This is a helpful insight.

*

Reading these six linked pieces, so soon after Mc’s death, rebreaks my heart. I am heartsick that he’s gone. But here he is on the page! His novels and novellas and stories and poems and craft essays are all out to there to discover. Start here. Then look for his latest novel One Kind Favor (a masterpiece) and At the Gate of All Wonder (my personal favorite) or find a copy of The Complete History of New Mexico (an early favorite) or 57 Octaves Below Middle C or The Fifth Station or . . .

*

Before reading “Six Portraits,” as with any Kevin McIlvoy story, you should first clear your mind. Take a deep breath. Think: trust the voice. Then follow it wherever it leads you.

Six Portraits

A difficulty

“No luck?” my wife said.

“The clear plastic bag is the problem.”

“Hard to do.”

“Impossible.”

“The goldfish,” she said. “A difficulty.”

“Oh,” I said, “I get goldfish, really get them. I can be them, draw them—still—and moving.”

“Fantails?”

“God, yes. All their lives they look middle-aged, muddled.”

“You’re better at drawing the goldfish, then?”

“Better at everything, at everything I try to draw. Except for—”

I shook my head.

She shook hers.

In the slipstream of the sheets, we expectantly undulated.

“Some wine?” she asked.

“A sip. Thanks.”

“Are human mouths still an issue?” she asked.

“And hands. Feet. And noses. I really hate the fuckin’ noses on people.”

She said, “A nose holds it all together.”

“Noses shouldn’t look like that,” I said. “Should they look like that?”

⸟

If a small ocean

Having read my mind, my wife asked a rhetorical inebriated question, a dance of sound and light resisting shape as a sentence: “Do you have Magdalen the Bartolommeo drapery the drapery do you still have the her that you keep in the all your all of your notebooks?”

“Oh, her drapery,” I said, because the gesture and the form of the Magdalen by Fra Bartolommeo pulled at me almost to the point of immobilizing me; the Magdalen is in every one of my notebooks.

I answered, “I would give my gallbladder for that kind of drawing magic. I get drapery. I can be drapery—do we have another bottle?” Inside, I was still fuming about the noses, about the fact that I could draw animal noses and tree protuberances and the grilles of Dodge Challengers and Olds Toronados and Studebaker Champions but not human noses, not for the life of me; and I could sometimes very poorly do that joining of shoulder and arm that does not easily come forward in a drawing except with the most skillful attention to edge-light; and I could do mouths though even a slightly open mouth with teeth and with the shadow evidence of a palate and tongue made me panic.

I looked into her wineglass for a vantage point.

Glancing at the wriggling likeness of my eyebrows and temples on the liquid surface, she thoughtfully avoided mentioning my buttocks–drawing period from which I never fully recovered. A little bit more sloshed, she said, “How people wear the people drapery—I’m glad I don’t haven’t won’t draw them.”

I did not say what I was thinking. That there should be Drawing Viagra, the smallest dose causing such swelling excitement that a simple chalk sketch of calf viscera could throb with tactile afterdeath expressions of weight. I was thinking that Restore apps should jolt the memory centers that help in drawing the tension-revealing shapes and not the mere lines of emergent forms. I was thinking that the Greek artists—the pantheon of the greats!—failed utterly at anatomical accuracy; that I was too old for the unending apprenticeship of the artist who wants to get drapery right, to render the mass and the volume under the masks the body wears, to show sunlight and wind dressed in the clothes pinned on the line and dancing, to draw the veiling and unveiling processes inherent in every manifestation of filling and flowing and flooding.

She knew I would not give in. If a small ocean must be carried from here to there, I do not rest from the task. I summon the transatlantic steerage space of my immigrant grandmother with her bulging valise, with her splintering bloodshot eyes gazing into the wasting faces of her children and her parents.

⸟

On the 6:25 a.m. Tunnel Rd E1–427

Slouching in sunrise concavity, the stranger reveals that she is Mildred Maneless-Gastaing, her tone suggesting I should recognize her. By way of apology, I say, “Something is terribly wrong with my memory,” and, rather lamely, I ask, “Pets?”

She holds them before her. “My beauties.” I feel her looking at me through the clear plastic bag, fixing her concentration on my face and, in particular, my nose. I explain that for two decades I studied the techniques for drawing transparencies because clear surfaces found me in every subject appearing before me. My anathemas come to meet me—more unrelentingly than ever, they find me everywhere. If I pass children on a playground, one will always have in hand a bubble-blowing wand. If I ask my boss at the bowling lanes for overtime pay, she removes her smeary glasses to avoid hear-seeing me. If I’m hiking alone, barely visible drapes of spiderweb windows appear. If I’m dreaming of sexual intercourse, thigh-high clear vinyl boots will vice-press my neck. If asking Mr. Tchelitchew the price for a fifty-sheet book of tracing paper, his unkind voice roils his vape fumes.

I tell Woman on Bus about van Gogh and my wife and Chaïm Soutine. Vincent van Gogh sold one painting, one painting in his whole life.

Is that how it goes? This was the thing van Gogh said to himself more or less constantly. So loud that people could hear: Is that how it goes?

Van Gogh was astoundingly productive between 1880 and 1890 and that was it, really, because fear ruled all his other years.

I tell Woman on Bus about the problem of her and her shape-shifting goldfish, that she and her clear plastic bag are a reminder that I will never meet a fellow passenger who does not inspire horror.

“Not much oxygen in the bag,” I say.

She says, “Very little.”

“You’ve come a long way with them?”

“A great distance.”

“And you are transporting your fish at 6:25 a.m.” They are in a bag that is beautiful. Inexpressibly beautiful.

“I am. Transporting them.”

When the bag settles again on her lap, the interpenetration of bus light and first light on her skin and on the bag-skin and on the scales and stressed crimson gills of the fish and on the windows and the not-quite-dull aluminum window frames, all of it causes me to wish I could have permission to sketch her nude, to render the intersection of her body with the bus’s hard surfaces, the event of her skin and the world’s vulnerable skin touching for that moment, which is something I could get and could be.

“Lively,” I say.

“We are. And bright, don’t you agree?”

⸟

Wineglass

The newly uncorked wine my wife offered was red wine splashed into the mouth of a simple clear glass with a clear stem, with the music of the spheres in its recurved rim.

The ways in which we two were graying had changed our dispositions in the space of our small home and small rooms.

As years passed we more generously imagined each other in readiness for further erasure.

Her eyes were green as acorn buds. The green of the veins in her mottled hands could be described with the very same pigment stain.

⸟

A wish

If, from memory, I were to draw my wife’s wineglass wrong, the perfect base would seem to be sliding off or floating at a tilt from the surface of the bedside table.

If I were to draw the glass almost right, an unnatural disturbance in the falling-leaves pattern of our wallpaper would result.

If I were to commit to the interactions of the glass with the resistant and receptive forms of lamp and table and bottle, that is, if I were to draw rightly and wrongly, after all these years I would be too insubstantial to be my own obstruction, and I could at last stop drawing what appears before me and could draw, as I truly wish, what reappears.

⸟

Oak

Unstable, unemployable, hungry and desperate for the most basic needs, unable to afford canvas, Chaïm Soutine met with patrons kindly sent to him by his sometimes-friend Amedeo Modigliani. By prearrangement, Soutine brought a framed painting of an oak tree, which, so they wished, would be the first of their many purchases from him.

He did not tell them that Oak was an overpainting.

In order to save money on canvases, he often bought very cheaply the amateurs’ lovingly rendered framed paintings always for sale at the junk markets, and he painted over.

In times of intensifying suffering, he painted over his own most successful attempts at Hare on a Green Shutter, at Return from School after the Storm, at Man Praying, at The Polish Girl.

In a pinch or in a fit of pique, he painted over canvases friends had given him.

His loyal friend Modigliani painted many portraits of Soutine, and in these portraits he gifted Soutine with eyes instead of the blank sockets that were Modigliani’s usual preference. The only one of these Modigliani portraits that Soutine had in his possession, he painted over. Over this portrait, which embodied Modigliani’s fully realized mastery, Soutine painted an ancient mossy oak: the bleak open hand of the trunk at its center, the whirling branches expressively deformed by the faintest accidental suggestion of a man in his hiddenness—of Soutine—in a serene portrait pose. Soutine had impatiently, insufficiently blotted himself out of context.

When the patrons began to pay him, he refused the large amount they offered, a charitable amount so great it insulted him.

He held the painting, taller than he, close to his body. He spoke from behind it.

“If you had given me one franc for my picture, I would have taken it,” he told the wealthy

woman and her husband, who found the painting unforgettably ugly, but who wished, after all, to please Modigliani.

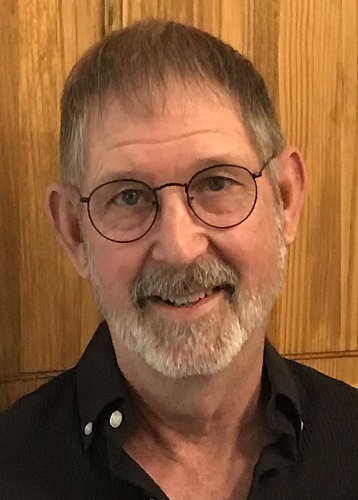

Kevin McIlvoy published six novels: One Kind Favor (WTAW, 2021), At the Gate of All Wonder (Tupelo, 2018), Hyssop (Triquarterly, 1998), Little Peg (Atheneum, 1990), The Fifth Station (Algonquin, 1988), and A Waltz (Lynx House, 1981); a collection of short fiction, The Complete History of New Mexico (Graywolf, 2005); a book of short fictions and prose poems, 57 Octaves Below Middle C (Four Way Books, 2017); and numerous poems in national journals. He taught in the New Mexico State University MFA program from 1981 to 2008, retiring as Regents Professor, and in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program from 1987 to 2019. For twenty-seven years he was editor in chief of the literary magazine Puerto del Sol. He died September 30, 2022.

Sebastian Matthews‘s book of micro essays, Beyond Repair: Living in a Fractured State, came out from Red Hen Press in 2020.

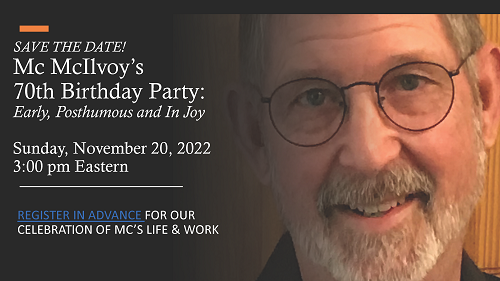

For those who would like to celebrate Kevin McIlvoy’s life, you can visit this site to register in advance for this event: