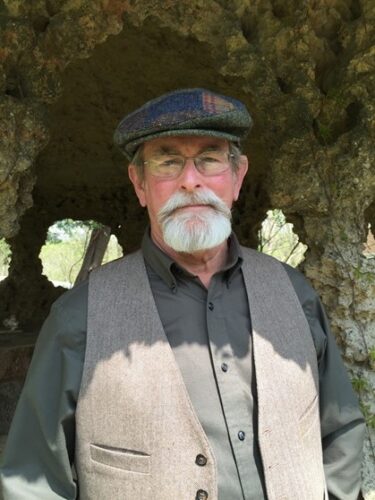

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: About a year ago, in our Issue 20.2, we published a special feature on writing in Cincinnati. When I read this essay by Richard Hague, a prominent local figure in the writing community (whom Pauletta Hansel mentions in her piece in that feature), it felt like a coda to that feature, with its focus on a Cincinnati landmark and its connections to his experiences reading a poem closely and personally. We’re glad to share it here:

Sitting Inside the Poem

I

In 1990 as part of a National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar fellowship to study the works of T. S. Eliot and Thomas Hardy at Oxford, I spent time touring London, including seeing the Elgin Marbles in their new special wing of the British Museum. In one long gallery, a run of the sculptures, originally from Phidias’s frieze on the Parthenon, stretches down the wall. I walked along it, looking closely; one section brought me up short. It features a cow, head raised, and, if memory serves, a garland or wreath around its neck.

Immediately, I perceived that I stood before the possible origin of one of the images in Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The poet himself, I knew, had viewed the Marbles not long after they were brought to England, and for that moment I had the sensation of looking through his eyes at something that became part of one of the greatest lyric poems in the language. The passage reads:

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks in garlands drest?

The feeling of being there with Keats was uncanny. On an earlier trip to Europe, I’d visited the Keats and Shelley Museum in Rome, and standing in the very room in which the poet died created something close to an eidetic memory. I could imagine the day after Keats perished of tuberculosis (which he suffered from even in that miraculous May when he wrote the odes), the impatient landlord gathering up the infectious bed and bedclothes and tossing them out the window onto the Spanish Steps below, where they were burned. I smelled the smoke, heard the cursing of the people walking by and a outburst in the hallway between the landlord and grieving Dr. Severn, who had refused Keats’s request of a life-ending dose of laudanum. I lingered in those hot rooms that afternoon, imagining the dying young man, far from his loved ones, slowly drowning in his own fluids. “Here lies one whose name was writ in water,” as his gravestone says.

Years later, I loaned a copy of Aileen Ward’s John Keats: The Making of A Poet to a student who got emotionally involved in Keats’s life, a kind of intellectual crush-at-a-distance both in time and space. I often wondered if she ever traveled to Rome, stood in that same room with the same disturbance of soul as I had.

Being physically near the poem or the poet, somehow, feeling him or her nearby, giving the self over to whatever dreams and bedazzlements such an encounter might engender, came to be an experience I wanted for my students. I just didn’t know how. But one day, years later, I found a way to make it so.

II

When I first came to Cincinnati to attend college, in the late summer of 1965, I had only recently begun to try my hand at poetry. I’d picked up a copy of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s A Coney Island of the Mind (City Lights Books, 1958) and composed a few poems in the Beat style, as well as a saccharine lyric about spring, which my critic and sort-of girlfriend had dismissed, quite accurately, as “icky.”

But sometime in September, after my orientation at Xavier University was over and classes had begun, I learned of a poetry reading to be held on campus. It featured a writer I had not heard of, John Knoepfle, a Cincinnati native and graduate of St. Xavier High School there. He was going to read from his book Rivers into Islands, just published by the University of Chicago Press. A few friends of mine and I attended the reading. By the time it was over and I walked back out into the night air along Victory Parkway (I know it sounds melodramatic, but sometimes life is a soap opera), my life had been changed.

I had spent a riparian boyhood in my hometown of Steubenville, fishing for channel catfish and carp, scavenging for interesting junk and lost tackle, and just hanging out during long summer afternoons. My grandparents lived so close to the Ohio River that you could smell it in their basement, as if it were flowing just beneath the foundation, panting out its green moist breath as it passed. Most of the kindling my grandfather had neatly stacked in the basement across from his coal furnace was driftwood from the river bank.

Up until Knoepfle’s reading, it had not occurred to me that the river might be the subject of a poem, or that the basement of my grandparent’s house might afford writing possibilities that would invite me to remember, and reimagine in very personal ways, scenes from the Odyssey, for example. But hearing him read poems set in actual places in Cincinnati I’d already visited or heard about—Ault Park, Alms Park, and Erie Ave. (on which, many years later, I would live), it came to me that my place and my daily experiences might also be made into poems. No need to range far afield with the Beats. No need to wish I had grown up in San Francisco so I could have gone to hear poetry at the City Lights Bookstore. Poetry’s raw material was readily available wherever “here” might be in my life—Steubenville; Cincinnati; Fly, Ohio—and I must be about my poetry’s business.

So, thirty-five years after that reading by John Knoepfle, I found myself with about eighteen students and my young teaching colleague, Nicki Hewald, sitting in Saint Rose of Lima Church on the banks of the Ohio River in Cincinnati’s East End. We were all engaged in The Course of The River, a pioneering interdisciplinary full-year course blending biology and literature, mainly, but with significant side trips into history, folklore, steamboating, the history and engineering of bridges, as well as regular local water sampling in my own neighborhood’s tributary of the Ohio, Little Duck Creek. We had a number of successes and a few failures, and the class went on for two remarkable years before its cost became prohibitive (two full-time salaries for one course).

Saint Rose’s is a marvelous place, blending Germanic riparian stolidity and Roman Catholic ornamental excess. Though its interior is colorfully painted and brightly illuminated, its exterior belongs to a class of what I have called, since my early architecturally uninformed years, “river buildings.” These are always brick structures dating from the mid-to-late-nineteenth century, within walking distance of the river, which have been flooded at one time or another in their history. It’s as if you can still smell the dried mud inside them; they have a kind of weathered survivor’s air about them that suggests all the troubled and sensational history of human dwelling on any river.

Our students and Nicki and I took seats in the front pews, the often-soaked floor beneath us. Among us were a neighbor of mine; a beautiful and artistically talented girl named Alicia Vargas; two senior boys ranked near the top of their class; and a young chap, Eric Rosemire, who had survived childhood leukemia but who was to be dead within a year in a car crash.

Just before entering, we had walked around to the back of the church, its river side, and stood lined up against the flood gauge painted on bright red brick. Towering above us was the marker for the 1937 flood, eighty feet (the flood stage is fifty-two), the greatest in recorded history on the Ohio; we tried to imagine being under thirty feet of water where we stood, the river now far off in its channel fifteen or twenty feet below the steep bank at the end of the parking lot.

As the students gazed around and posed for a photograph beneath the gauge, I could see that even in their adolescent cool they were clearly moved by the place. I was reminded again of how infrequently kids go to interesting out-of-the-way places in their own towns: many of my creative writing students that same year, for instance, had never been to Findlay Market, one of the oldest continuously operating open-air markets in the country, where the people-watching and the diversity is unparalleled in the city. One of the untapped resources for any writing teacher, I think, is the city or town or countryside around the school. Go out into it as strangers on a visit, like tourists in your own wondrous whereabouts, and pay new attention.

Saint Rose’s steeple has been used for more than a century by riverboat pilots as a way of lining up their tows to navigate the great sweeping bend that begins just upstream on the Ohio. Its function is practical in other ways too; the town of Bellevue, Kentucky, directly across the river, helped to pay for a recent repair of the clock, which busy Kentucky townspeople still use to check the time.

Incidentally, the little Kentucky towns of Bellevue and Dayton are closer to my school than most of the Cincinnati neighborhoods our students come from, but separated by the river. Located in another state, they seem foreign places. “How many of you have ever been to Dayton, Kentucky?” I asked. One or two hands went haltingly up. A river is a powerful presence in a landscape, and our American habit of making rivers the borders between states and nations (West Virginia and Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky, Illinois and Missouri, Texas and Mexico, to name a few) underscores the presence of river as divider. That day, we were brought together, though, teachers and writers in quest of images and ideas.

The interior of Saint Rose’s is an unapologetic blandishment of color, shape, and light. Over the altar stands a life-size statue of Rose of Lima, whose story is akin to the magical stuff of a Gabriel García Márquez novel. She was an incorrigible teenager who refused her parents’ wishes that she marry; she took up her abode in a hut in their garden, where she “mortified” herself by, among other things, wearing a crown of thorns. She did sewing to help the family out of difficult times (there’s a pincushion painted high on the wall behind her).

Here in church, she is holding a bunch of red roses and is surrounded by an arch of maybe a hundred electric bulbs that glow garishly during Mass. With her in the sanctuary are the Infant of Prague, Saint Joseph, Saint Catherine of Siena, and out in the church, statues of the Pietà and Saint Martin de Porres—an intense company of virgins, martyrs, totems, saviors, inspirers.

III

One of the works John Knoepfle read that night long ago was the poem that gave him the title of his collection Rivers into Islands. It is about this very church, and begins:

It looks from the hill like something

Fra Angelico painted, the red

rectangular lines and the bricked bell

steepled out of time.

Continuing in the same tone, the poem sets the scene in which this strange sainted girl from Peru is remembered in a town full of Germans “on the unliturgical river.” After alluding to her refusal to marry, and accounting for the Rose motif in the church’s decoration, Knoepfle concludes:

Once I thought the rococo Christ

had made her a violent dove and held

her trembling in his hand like a bell.

I am not so sure of this today.

She may be undiscoverable, like silt

slow rivers encourage into islands.

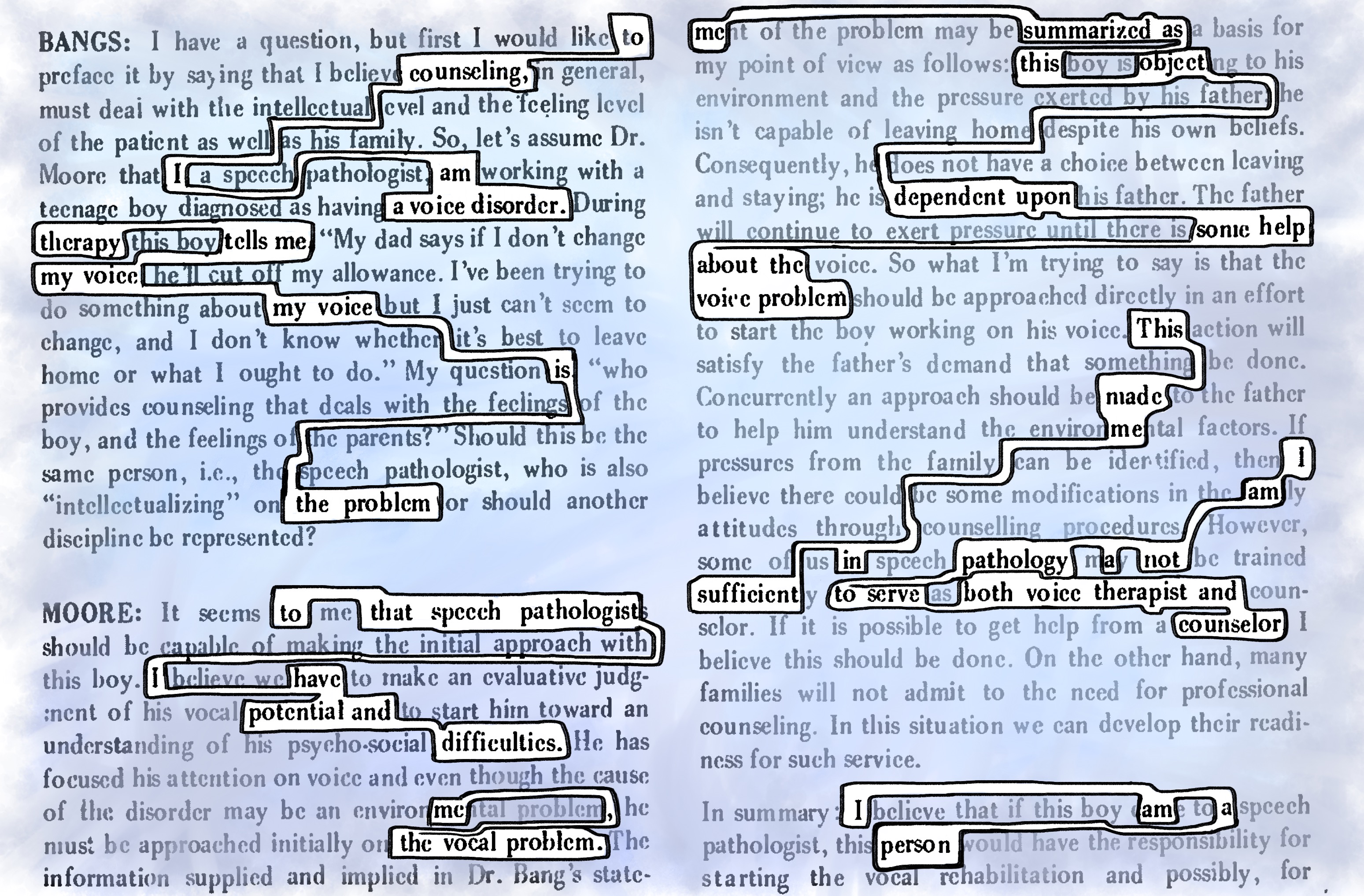

Aside from the poem’s accurate imagery and its acknowledgment of mystery in the lives of the saints, it is intensely local, reverent, dense with placed-ness. Reading it to students spread out down a couple of pews, my voice echoing in the high-ceilinged, over-the-top interior, I saw the poem as Knoepfle saw it. I wondered when he’d been in the church last, when his knees had last bent as incense floated out over the devout.

I cannot be sure—the effects of any learning experience may be, at the time, like the slow process of island building in the poem, “undiscoverable”—hence the absurd narrowness of the kind of testing we do now of students, looking for immediate answers to tiny, factual questions and ignoring the larger ones whose answers will, after actual life experience, ripen into character, insight, wisdom, action.

Still, I think being in that church, immersed in the poem, soaking up the atmosphere of devotion and loyalty that filled the place just as surely as floodwaters had filled it in the past—all of this must have meant something to those students. And even if they couldn’t put it into words that day, I trust they have remembered it.

How often, outside of these hyperaware “spots of time,” as Wordsworth called them, are we really alive, tuned not only to “now” but also deeply to “before,” maybe even to “always”? Sitting inside the poem, we are open to epiphany, which does not always come in some cinematic flesh-melting Raiders of the Lost Ark flash, but quietly, calmly, almost secretly: like the slow, beyond-mere-pictorial-to-almost-corporeal blooming of this little painted saint’s sweet Peruvian roses.

Writer’s Statement:

Like many things I have written about over the last half century, this experience began in school. Under a progressive principal, we teachers at Purcell Marian High School in Cincinnati had opportunities to create interdisciplinary classes, thus breaking down the troublesome barriers between, say, literature and science, or trees and religion. At the time we followed an alternating A/B schedule, with four one-hundred-minute periods per day. This allowed enough time for field trips without disrupting attendance at other classes. Since our school was just a couple of miles from the church in the essay, we could go there, explore its little museum, climb the clock tower, ask questions of the pastor, have leisure to briefly read and reflect in situ, and get back in time for the next period.

This was one adventure in The Course of the River, which I team-taught for a couple of years, and then taught solo for several more, including one semester adapted to a freshman composition class at Thomas More University when I was writer-in-residence there.

The poet John Knoepfle received his PhB from Xavier University in 1947, the year I was born. Many years later, he and I met for the first time and appeared in Dorothy Weil’s video documentary tribute to the Ohio River featuring our poems, We Listen to the Water: Ohio River Voices (TV Image, Inc.) Anyone will need more than good luck to find this, though the University of Cincinnati and Miami University libraries have reference copies in house.

Richard Hague is author or editor of twenty-three volumes of prose and poetry, most recently Continued Cases (Dos Madres Press, 2023), poems political, satirical, and environmental. Awards include the Weatherford Award in Poetry, Poetry Book of the Year from the Appalachian Writers Association, and Ohio Co-Poet of the Year.

![Special Feature: “Mrs. Williams [Or, A Study of Postmodernism and the Many Ways That Walls Are Broken]” by Julie Marie Wade](https://www.cincinnatireview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Wade-Website-440x264.png)