Special Feature: “My Great Hunger” by Stephanie Early Green

28 Minutes Read Time

Literary Nonfiction Editor Kristen Iversen:

When I first read Stephanie Early Green’s essay “My Great Hunger,” I was struck by its candor and relevancy. It’s not easy to face one’s own insecurities, particularly when it comes to body and image, and to acknowledge the fact that these feelings are often passed down for generations, particularly for women. (My mother, too, felt insecure about her appearance and her relationship with food, a feeling she passed down to her three daughters). Here’s more from the author:

Writer’s Statement:

I come from a big, complicated family, which means big, complicated problems, all mediated by cultural expectations of keeping up appearances, not airing dirty laundry, and not betraying the family. As a rule, in my family we talk around our issues with food but avoid speaking of them directly; no one wants to besmirch anyone’s memory, or cast blame, or sow bitterness. For years, I felt extreme shame about having struggled with an eating disorder and told almost no one about it. I didn’t even tell my husband that I’d been diagnosed with anorexia as a teenager until we’d been married for several years. But at some point over the last few years, living with a secret like this—a secret that spans generations—began to feel burdensome, and I was ready to put that heaviness down.

I wrote this essay mostly to work through and articulate something I’d slowly begun to sense: that my eating disorder was not my fault, or my mother’s fault, or my grandmother’s fault, and that shame and blame were not useful lenses for understanding what had gone wrong, why my inner sense of my own hunger had gone so haywire. While my anorexia was, perhaps, a genetic and cultural inevitability, what I’ve also realized is that my children’s relationship with food does not have to follow the same path. This, to me, is a hopeful and liberating thought.

This is my first published essay, and I was extremely nervous about putting such a personal story out into world, especially since this is not just my story, but the story of my mother, her seven sisters, their mother, and back and back. When I finally let my mom read this essay, I was worried she’d be hurt or offended, but, to my great relief and gratitude, she loved the work and was moved by it. I’m very grateful to her and my dad for giving me the space to write this essay and, more generally, for always supporting my writing. I know this topic is uncomfortable for everyone in my family and I hope that, by being honest and writing with love, I can lift some of the shame that clings to this topic.

My Great Hunger

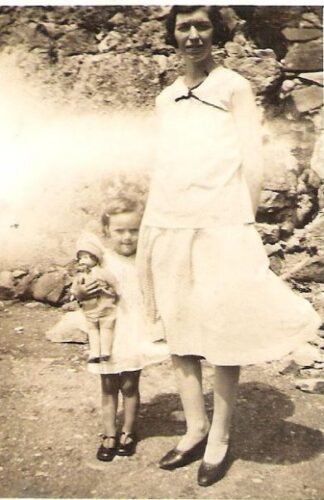

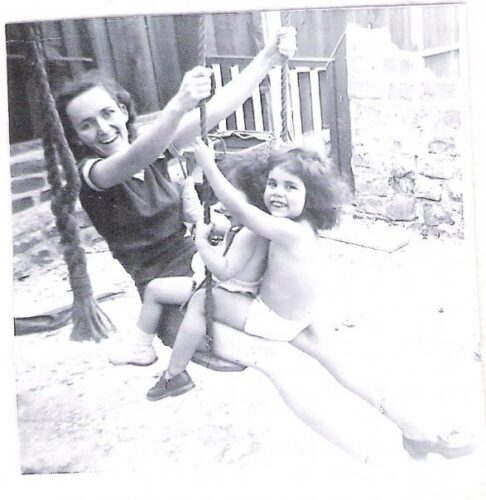

(All photos courtesy of the author)

I always left my grandmother’s table hungry. The meals she served were small and overcooked. White rice or boiled potatoes (never both), a dry hunk of lamb or pork, a ramekin of canned corn or peas. No second helpings. Never more than one starch on the table. No dessert. She did not seem to understand how much other people ate, how hungry we became. She knew only her own limited appetites and served food accordingly. Maybe she figured the doll-size portions she consumed should be good enough for everyone. Or maybe she was afraid of what would happen if she let us have bread and potatoes, if she set out a gallon container of ice cream and a handful of spoons, if she threw up her hands and said, Eat! Please, eat!

My grandparents’ kitchen in San Francisco was green-and-white tiled and filled with dim, foggy light. I have memories of my grandmother, Josie, standing at the counter, making endless cups of milky Red Rose tea, her countertop kettle forever boiling. I have no memories of her cooking and few of her eating. A typical lunch for her was a slice of sourdough toast with a thin smear of spreadable brie. A piece of fruit, eaten delicately. My grandfather, on the other hand, was always in the kitchen. He made chorizo and beans, toast with butter, scrambled eggs. He was up with the birds and believed in a hearty breakfast. My grandmother seemed to resent how we all loved Pop’s buttery toast, his eggs fried in bacon fat. She had no appetite in the morning. Not much of an appetite at all.

While my grandparents were alive, most family gatherings were held at their house. To compensate for Josie’s tendency to underfeed, her children and grandchildren had learned to adapt, bringing vast quantities of food to lay on her table: ice-cream cakes, cheese platters, dips, casseroles, chips, crackers, pretzels, pies. We piled the food on the dining-room table and joked, every time, that we might have overdone it. But we had to overdo it. If we didn’t, there would not be enough.

We all ate too much at these gatherings, crouching around coffee tables, shoveling crudités and dip and beans and meat and slice after slice of sourdough slathered in butter into our mouths until we groaned in agony. “Why do we do this to ourselves,” we’d say. “Why can’t we just eat like normal people?” Then we’d go back to the table for dessert.

Josie would sit in her blue armchair with a cup of tea balanced on her knee. She did not indulge in the dips, the cheese, the pie. Once, she told me, “You know, I don’t really think much about food.”

***

Josie was born in 1927 in Athy, County Kildare, to an unwed mother. My great-grandmother sent her infant daughter to live with family while she went to England to work as a nanny, cuddling another family’s babies but not her own for three years. Eventually, she and my great-grandfather reunited and married, and they came to collect Josie, their firstborn, whisking her across the country to Galway. This must have been frightening for a three-year-old, to be pulled away from the only family she knew, taken by strangers claiming to be her parents.

I do not know much about the rest of my grandmother’s childhood, but I imagine it was grim, based on the few anecdotes she shared. Josie and her eleven siblings scraped seaweed off rocks to eat. She was reprimanded by the nuns at her school for being too smart for her own good. She left Galway for San Francisco when she was nineteen, accompanied by her father and next-youngest sister. It took my great-grandfather eight years to bring his other ten children to California, but eventually he succeeded in uprooting his family, planting them in new soil. But of course they hadn’t left Ireland behind, not really.

***

Josie married my grandfather, Mark, on Halloween Day 1947, and my mother was born a scant ten months later in early September 1948. After my mother, Josie and Mark had eight more children—seven girls and one boy smack in the middle. Josie bore nine children in fourteen years. She was constantly pregnant but never lost her svelte figure. When she was pregnant with her eighth child, she was known to boast that she’d gained only eleven pounds. The baby weighed seven pounds.

My grandparents raised nine children in a crowded house in the Sunset District of San Francisco. Big, unruly Irish-Catholic families were common in the neighborhood. Like my mother and her siblings, many of the neighborhood children would grow up haunted by demons: drugs, alcohol, food, mental illness. There must have been something in the water. Or else there was something in the water that our ancestors drank, hands cupped to hungry mouths. My grandmother could not have meant for her children to grow up tortured by food, to learn to despise their bodies, even though that is what happened. I remind myself often that she did the best she could.

***

Soon after I turned fourteen, I got my first period. By the end of that year, my period was gone, because fourteen was the age when I stopped eating. I do not remember making the decision to stop, only that at some point eating became intolerable. My mother would make me tuna sandwiches on bagels, the tuna mixed with mayonnaise. I would scrape the tuna into the trash and nibble the edges of the bagels, only the dry parts untouched by the mayonnaise. It was the 1990s and I was terrified of fat. I subsisted on fat-free cheese slices, fat-free yogurt, skim milk, apples, pretzels, raisins. I refused to eat the meals my father cooked, dishes I used to love: spaghetti and meatballs, clams linguine, roast chicken. I haunted the cookbook section of the public library, poring over recipes I would never make. I collected food magazines, squirreling them away in my room. I studied veganism and the macrobiotic diet, which consisted of broths and seaweed and seemed like good institutional cover for a raging eating disorder. I ran longer and longer distances. Some days, I would put on my black Speedo and run three miles to the pool and swim laps until I was dizzy, then run home. Finally, when I reached corpse-like thinness, my mother put her foot down. Enough is enough, she said. You need help. We were in the car, our wood-paneled Dodge Caravan, and I banged my head against the window until she screamed.

The summer before ninth grade, I was forced to see a doctor, a dietitian, and a therapist. This treatment plan was necessary and correct, the only hope of curbing a burgeoning eating disorder, but I seethed with anger at my parents. I have only hazy memories of the doctor and dietitian, but I remember the therapist’s office, set in the ground floor of a beige office building. The windows were framed by gently waving leaves, and in other circumstances, the space might have been cozy, welcoming. I hated being there, hated the therapist. I showed up to my appointments wearing very short shorts, proud of my sinewy thighs. When I was ten, my figure-skating coach had told me I had “big legs,” and I’d fantasized since that moment about having colt-like thighs, knobby knees, pin-thin ankles. Long limbs, however, were not genetically achievable. The best I could do was starve away the muscle, the fat, leaving only the bones and gristle, a carcass.

My motivation for recovering from anorexia had little to do with what was said in those therapy sessions. My goal was not to inhabit my body without shame, because I figured that was impossible. I wanted to avoid being sent to a treatment center, first of all, and second, I wanted to be able to run again. During my treatment, I was not allowed to do any exercise, although I skirted the rules by walking the three miles to my high school and back every day, toting my backpack and clarinet case. The doctor and the dietitian agreed that I would not be allowed to return to sports until my period came back and my resting heart rate climbed to sixty beats per minute. I met these goals at the beginning of cross-country season my freshman year, and I made varsity. I threw away the cooking magazines, the Speedo, and the tiny shorts, all the relics of my anorexic life. If I could have burned all evidence of my eating disorder in a bonfire, I would have. I wanted to pretend the whole thing had never happened.

I managed to maintain a normal weight for the rest of high school, and beyond. I never again plunged myself into the cold waters of starvation. But one’s brain does not simply snap back from anorexia nervosa. You do not wake up one day and think, How silly I was! The process of recovery, of not actively trying to destroy your own body, takes years, decades. Only now, at age forty-one, a mother, do I have a relationship with my body that approaches “normal,” and only because I’ve worked out a way to stay thin without resorting to the extreme methods that I once used. If I weighed twenty or even ten pounds more, I have no doubt I would go right back to torturing myself. I wonder if by the time I am an old lady, I will still care how much I weigh. Probably. I am nothing if not realistic.

***

I learned to hate my body from my mother. This sounds accusatory but is not. My mother learned from her mother, who doubtlessly learned from her own mother, who was born around the turn of the century, fifty years or so after the end of the Irish famine. The famine, also known as the Great Hunger, lasted from 1845 to 1851. By the end, over one million people had died of starvation or sickness, and another two million had emigrated. My grandmother’s family were among those who stayed in Ireland, who survived but did not escape. Although I know nothing of how they scraped by, or about the experience of watching loved ones, neighbors, and friends disappear, I know what it is to starve. The difference, one might argue, is that unlike my ancestors, I chose my hunger. But anorexia is not a choice, any more than depression or anxiety is a choice. And my particular Irish Catholic brand of anorexia, tangled up with religious guilt and the veneration of suffering, was born out of a long legacy of hunger, or what Australian writer Judy Atkinson calls “trauma trails,” the way catastrophe trickles down through families.

Intergenerational trauma is handed down, like a defaced heirloom, from generation to generation. Populations that have experienced extreme, prolonged stress pass along psychological damage to their children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren. This phenomenon has been well studied in the descendants of Holocaust survivors, but it exists in many populations, including Native Americans, African Americans, and the Irish, including Irish Americans. The particular trauma of the Irish famine manifests in the descendants of those who starved 170 years ago in a number of ways: drug and alcohol abuse, depression, anxiety. And, of course, troubles—obsessions, disorders, traumas—around food and eating.

In her essay “The Need to Feed,” journalist Carolyn Ramsay writes about her obsession with feeding people, a preoccupation she inherited from her Irish American grandmother, the child of famine emigrants. She notes that many Irish Americans “have obsessions about food that, due to the long silence about the Famine, we’ve struggled to comprehend.” Many of Ramsay’s friends of Irish ancestry told her stories about their families and food. “One said her affluent mother always prepared too little food for her family—six chicken legs for a family of seven, for example—so that each dinner began with a scramble for food. Another friend’s Irish-American grandmother limits herself to tea and so little food that she must occasionally be treated for malnutrition. She does this despite a full bank account.”

Reading these stories, my stomach lurches with recognition. The starvation mentality that hung over my grandmother’s house was not unique to her, a quirk of her individual psychology, a mean streak. Her inability to feed herself and others was a kind of inherited blindness. The obsession with food she passed on to my mother, and my mother to me, was not her fault, not really. I find comfort in this, now that she’s gone.

***

When I was growing up, my mother was always on a diet. There was the Eat More, Weigh Less diet. The one where she could eat as much as she wanted until a certain time of night, when she would have to stop. The one where she didn’t eat carbs. The one where she didn’t eat fat. The one where she didn’t eat meat. The SlimFast Diet. The South Beach Diet. The Atkins Diet. The Mediterranean Diet. My mother, who was and is objectively beautiful, complained about how fat she was, how hideous. She punished herself with runs and walks, spent hours in our windowless basement doing Tae Bo and lifting weights. She never seemed happy with her shape.

My mother never commented negatively on my body, not once, but her self-hatred was like smoke, seeping into the furniture, the carpet, my hair. At four years old, I stood on my parents’ bed, looking at myself in the mirror over my mother’s dresser, and hating how my stomach stuck out. I remember that I was wearing a floral-print dress and white tights. I thought, “I am so fat.” I was in nursery school.

Troubled relationships with food were rife in my mother’s family. Some of her sisters were overweight. Some were alarmingly thin. Some ping-ponged between these two states, ballooning and shrinking over the years. Looking at family photos with my mother’s sisters always included a chorus of “Oh my God, look how fat I was” or “Look at how skinny she was!” or “Ugh, my ass in that dress.” In my generation—seventeen first cousins—many of us have shed and gained large amounts of weight, over and over. Despising our bodies is a family contact sport, one that yields countless injuries.

When I was in elementary school, my grandparents acquired a large print of a painting, which they hung over the faded blue couch in their living room. The painting, by Francisco Zúñiga, is called La Mecedora (“The Rocking Chair”) and features two women: one is seated in a teal chair, thick arms crossed over her chest and a tired expression on her face; the other reclines in a rocking chair, eyes closed, one leg propped on the other, arms folded behind her head. The women have brown skin, black hair. They are Mexican. And they are large. Buxom. Shapely. Fat.

The first time the family gathered at my grandparents’ house after the installation of La Mecedora, Josie nodded at the two portly women in the painting and said, lightly, that they looked like two of her daughters. The two biggest daughters. This comment, when sliced apart, revealed several layers of insult. First, there was the issue of race. Josie’s husband, my grandfather, was Mexican American, and his family resembled these women: fleshy, dark, no-nonsense. As different from pale, birdlike Josie as night from day. But there was also the issue of beauty. The women in the painting are unsmiling, unlovely. They look like they’ve spent the day wringing clothes through a mangle or cooking over a hot stove. They look fed up and tired. But above all, they are fat. This was the real insult. You see, the fear of fatness was ever-present. The fear was in the air we breathed.

***

I grew up in an affluent white suburb of Detroit. Our public-high-school parking lot was packed with shiny new Mustangs, Jeeps, and, for a brief and unfortunate window of time, PT Cruisers. People’s parents were auto executives, engineers, accountants, lawyers, doctors, dentists, chiropractors. One boy’s grandfather owned a popular sports team and a wildly successful national chain of pizzerias. Some of my classmates were blissfully happy, I imagine, growing up in the lap of luxury, skiing in Vail and sunbathing in Florida, but there was a dark undercurrent in my school, a sense that the kids were not all right. There were stints in rehab, pregnancies, abortions, arrests. After the Columbine shooting, there were bomb threats, brooding boys who stalked the hallways in trench coats. Self-destructive behavior was de rigueur.

In this way, I was no different from anyone else. Eating disorders ran rampant in my high school. By my sophomore year, anorexia and bulimia had reached epidemic proportions, worrisome enough to school administrators that they held an Eating Disorders Awareness Day and forced us all to sit in the auditorium and listen to earnest speeches by teachers and a few brave students willing to admit that they, too, had starved themselves. One of the girls who spoke was a popular junior, a pretty girl with long brown hair and blue eyes, who talked about her struggles with anorexia. What she did not mention, but what we were all thinking, was that her refusal to eat coincided neatly with her father’s arrest for a series of bank robberies in the area. The shame must have been unbearable. Her anorexia, to me, made perfect sense.

The dominant girls at my school were thin in a way that only WASPs can be thin, their blue veins shining through their tiny wrists. I longed to look like them. But my genes were coded to hold on to fat, to hunker down for hungry times. Even at my thinnest, when my skeleton jutted through my skin, I still didn’t have the coltish look of the popular girls. My bones were not the right shape. I kept trying anyway.

***

In eighth grade, one of my best friends was another high-achieving, tightly wound nerd. We attended the same Catholic church, had been steeped in the same lessons of guilt and sacrifice. We developed anorexia side by side. We became running buddies. We traded bags of homemade granola, which we then refused to eat. One afternoon, a year or two before we became anorexic, I had been at this friend’s house having a snack when her mother, a slender, put-together housewife, drifted into the kitchen and commented on my “big appetite.” The shame of being seen eating, of having an appetite that was so big as to be noticeable, remarkable, burned like an ulcer. A few years into my recovery from anorexia, I looked back at this interaction, my friend’s lipsticked mother hovering over us in the kitchen, and felt sorry for myself, yes, but sorrier for my friend. Her mother’s body hatred was directed not just inward but outward, at her own child, at her child’s friends.

I used to wonder if I’d caught my eating disorder from my environment, like a nasty cold going around. There was my toxic high school, my friend’s judgmental mother, the Seventeen magazines full of diet tips, the fetishizing of pop stars’ concave stomachs. How could I not become anorexic? But of course, not everyone did. I was marked for a troubled relationship with food. There was a seed buried inside me, a black flower that would bloom if given just a small drink of water. This seed was planted hundreds of years before my birth.

***

The year I stopped eating was also the year I became religious. I was confirmed in eighth grade and took my formation as a Catholic seriously. I wrote out long prayer lists by hand. I felt responsible for praying for every person on Earth, and the weight of the collective suffering of humankind pressed me down. Guilt was an essential component of my faith. I was taught, directly and indirectly, to feel guilty about everything. I recall a homily given by our parish priest, a cadaverous man who wore a gold Rolex, about how Jesus wouldn’t have taken a Tylenol if He had a headache, and so neither should we, His people. Offer up your suffering to God, we were told. (Appropriately enough, when my grandmother got an email address in the late 1990s, her handle was oferitup@aol.com.)

I absorbed the Church’s warning that you must be ever-vigilant to avoid gluttony. This means, in Catholic theology, not simply not overeating but also being concerned with what you eat and how and how often. You are not to eat too quickly or be too picky. You are not to prefer expensive, rich, or finicky foods. You are not to snack throughout the day. You are to fast in order to, as Thomas Aquinas wrote, “bridle the lusts of the flesh.” The idea is to gain control over one’s appetites, to master one’s own desires. All of this, obviously, is a recipe for disordered eating.

The coincidence of Catholicism and eating disorders, particularly anorexia, has been studied, with mixed findings. One 1988 study found an increased prevalence of eating disorders among Jews and Catholics, two guilt-laden religions that include populations that have experienced significant cultural trauma. I’m sure these findings would surprise not a single Jew or Catholic. But no one can say definitively where eating disorders come from, what precise blend of ingredients creates each individual’s poisonous mix. A number of factors may have contributed to my anorexia: an inborn tendency towards perfectionism, my Catholic upbringing, my mother’s attitudes toward her own body, the suburb where I grew up, a family history of starvation. Suffice it to say that my genetics piled the tinder, and my environment threw the match.

***

When I began to eat again after my anorexia, I ate very fast, hardly chewing my food. One day I was eating pretzels by the handful as my mother watched. She shook her head and said, “The way you eat reminds me of my mother. Like you can never get enough.” This comment stung. How dare she criticize the way I eat, after I’d spent a year not eating at all? But now, decades later, I can see that my mother was recognizing an inheritance, a defect she’d received and passed down to me. She was saying she wished things could have been different for me, for her, for her mother. But neither of us knew, then, how to make that so.

***

My oldest daughter became a picky eater as a toddler. She tolerated my spooning purees of vegetables and fruits and meats into her mouth until eighteen months, when she started refusing food, turning her button nose up at all her previous favorites (or what I had imagined to be her favorites). Her pickiness worried me. Had I done something wrong? I must have. The blame for any issue with a child’s eating almost certainly lies with the mother, I thought.

When she was born, I had dedicated myself to ensuring she would be the healthiest child to ever walk the Earth. I suffered through breastfeeding for a full year. I spent hours in our cramped galley kitchen steaming and blending baby food, then freezing the purees in silicone trays. In our freezer I amassed a rainbow of nutritional cubes: spinach, cherry, mango, butternut squash. My baby, I decided, would be the child uninterested in candy who snacked on handfuls of snap peas. She would not eat processed foods. Sugar? Heaven forfend!

For the first two years of her life, I never let so much as a graham-cracker crumb pass her lips. When she was nine months old, I went to a diner for brunch with some friends I’d met through a support group for new mothers. While they fed their children bites of their waffles and eggs, I took from my diaper bag containers of purees and tiny bits of soft meat, which I arrayed on a silicone plate for my daughter. One of the other women held up a baggie of cereal and asked if my daughter wanted any.

“No, thanks,” I said, smugly, “she’s actually never had a processed carb.”

The other mother did her best not to look as sorry for my child as she must have felt.

My perfect baby, you see, ate only whole foods: lentils, blueberries, kale, salmon. Until, one day, she didn’t. By the time she was five, my daughter would have been happy surviving on warm milk and boxed macaroni and cheese. She had become the child who ate just off the kids’ menu, who hated vegetables, who refused to try new things. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and my family was stuck at home, eating every meal together, the extent of my daughter’s pickiness began to frighten me. What if she was always like this? What if she never ate a vegetable? I knew a girl my freshman year of college who had arrived on campus never having tasted tomatoes or chicken. This is what I feared for my daughter: being a rube, a weirdo, a person who must be coaxed into tasting a tiny bit of innocuous food.

When my daughter was six, I hired a pediatric dietitian who specializes in getting picky eaters to broaden their palates. The intake forms asked my husband and me to describe our own histories with food. I scoffed at the absurdity of fitting my complicated (read: utterly fucked-up) relationship with food into the little box on the form. The form then asked us to describe our fears around food. Again, impossible: my fears around food were as unseen and innumerable as germs, lurking in the air, virulent. Finally, the form asked if we were afraid of our children getting fat. I wanted to write, Of course not. What kind of terrible, vain mother would care about a thing as inconsequential as the size of her children’s bodies? But I was afraid. This fear, unspoken, had been lying in wait since before my children were born, when I was imagining perfect lives for them. I wanted what every mother wants: for my children to be healthy and happy. But underneath was a dark and shameful wish: I wanted them to be thin too.

As soon as we began to work with the dietitian, I had to reckon with what my children saw when they watched me interact with food. I thought I was hiding all my food neuroses from them, that they didn’t notice that I never ate dessert or that I was always the first to finish eating at dinner. But they saw everything. I used to not allow myself to have a bite of food before ten o’clock in the morning. Then I noticed my daughter noticing.

“Mommy,” she asked one morning, looking at me with her big brown eyes, “aren’t you going to eat?”

Now, I force myself to eat breakfast every morning. I want my daughter to see me eating. I do not want her to see how uncomfortable eating makes me, how I dislike the feeling of food in my stomach in the morning, how I prefer to feel light and hungry until I have earned the right to eat, after my morning workout. I never want her to know these things about me. I am filled with shame about my own obsessions with food, habits I can’t seem to break.

Years ago, I bought a book about intuitive eating, a framework for becoming attuned to one’s own body and hunger cues in order to “achieve authentic health.” The principles of intuitive eating include honoring your hunger and respecting your body and its genetic blueprint. Eating intuitively requires that you let go, completely, of diet culture and restrictive eating. A few pages into the book, though, I abandoned it. The idea of releasing my many rules and restrictions around food made me panic. I didn’t want to let go of my food rules. They were what kept me safe.

But now I want to let go. I want to be free. I want to break the chain that extends across time, binding me to my fearful, starving ancestors. I worry, though, that this breakage might not be possible. I might be too far gone, too damaged. But it is not too late for my children. Knowing that they will not be tethered to hunger like I was, like my mother and my grandmother were, is my greatest comfort. Every time I sit down with my daughter to eat, I watch her watching me. And I put food in my mouth and smile.

My grandmother is gone now. While she was alive, we never acknowledged our family’s troubles with food. If I could see her again, I would tell her, It’s over now. We’re better. Please, eat.

Stephanie Early Green‘s short fiction appears in Narrative, the Chicago Tribune, New Ohio Review, Juked, and elsewhere. She is a current MFA candidate in fiction at Warren Wilson College. She lives in Virginia with her husband and three children and is at work on a novel.