Special Feature: “Distilling Ephemera, Translating Observations,” by Michael Colbert

5 Minutes Read Time

Assistant Managing Editor Bess Winter: Michael Colbert’s “Sin, Nebraska,” a story of a relationship that makes meaning through the objects, media, and ephemera that its narrator accumulates and steals, is published in issue 20.2. We were delighted when Michael agreed to write something for our website exploring the effect of objects and ephemera on his writing—and to mix media, in the process!

Distilling Ephemera, Translating Observations

Artist’s Statement:

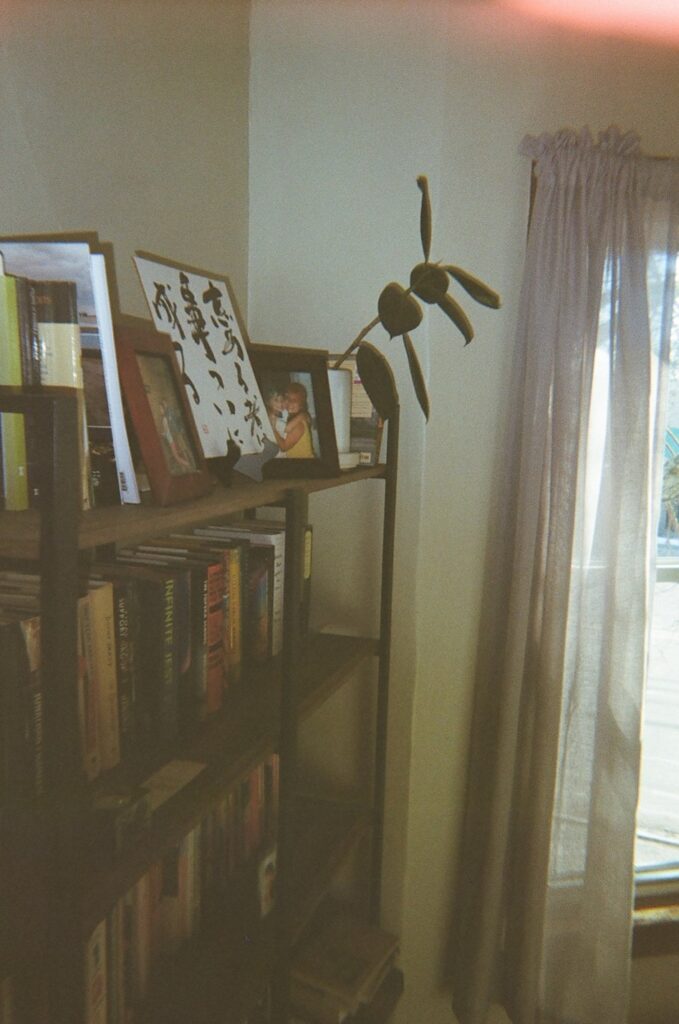

I picked up a disposable camera at my local camera shop to capture images of my ordinary surroundings. I set out to photograph collections of objects in order to think about the bric-a-brac that populates my life.

The images that came back on the developed roll surprised me in their discontinuity. The process of drawing connections between my thoughts on writing with ephemera and the imagery I’d collected of it mimicked the writing process I discuss in the essay.

An Audience of One

A couple of years ago, a friend said talking to me was like performance art. She never knew exactly what was going on. This completely surprised me but also made complete sense. Were I to actually perform on a stage, I’d back off—I couldn’t handle the attention—but the idea of performance is a different story.

Sometimes it’s about living in the bit—inhabiting a joke, a personality—but sometimes it’s about making connections, seeing things, creating dialogue between one idea and the next, and through the drama saying something new.

Pulling the World In

I interviewed Jenny Fran Davis about her novel, Dykette, and we got to talking about references. Her book is full of them—the protagonist studies media and literature—and whether referencing ethnographies or The Sopranos, the narrator uses external texts to interpret her relationship to the world. “Everything makes me think of something that already exists, and then that makes me think of something that’s already existed before that,” said Davis. “Everything feels like it’s in a loop, referencing both itself, past things, and even present things that are going on at the same time.”

Looking Outward

For me, so often the self makes sense through these other media. I have a powerful memory for the details of others’ lives, remembering papers I didn’t write or inside jokes I’m not part of. This applies to media too. Lines from TV shows, even the way a song cuts into a scene, can embed in my brain forever. From there, they might become part of how I reinterpret something I see.

But how do you distill meaning for the reader, especially if they’re unfamiliar with the reference?

How do you constellate meaning between these disparate universes?

What Sticks Out?

The opening line of “Sin, Nebraska” played in my mind for ages. It magnetized other things towards it: a troubled relationship, a hideaway. Then the story kept growing: cat hoarding, Barthes, Catholicism, bottom shame.

This eye for ephemera is something we can cultivate. I used to start classes by asking students to journal strange things they’d observed over the past few days: snippets of eavesdropped conversation, people doing weird things on campus or downtown. The semester always started slowly but then picked up speed. We started seeing so much more in the world as we looked for it.

Sometimes I’ve felt that in drafting a short story I’m just throwing a bunch of things together and seeing what sticks. It can be an experiment—what emotional resonances emerge when you put together hoarding pets and pawning stolen jewelry?

I love this part of the process, when the raw stuff of life begins to coalesce, if awkwardly, into one greater composition. At first, I like the clunkiness—it feels more representative of everyday life where some things coexist because of coincidence and not for some neat, plotted reason.

Temperature Reading

A question from an MFA classmate plays regularly in my head, “Where’s the heat in the story?”

Pulling together the ephemera requires a temperature check.

Why does the Kitty Genovese simulation in Girls haunt me?

What’s so emotionally charged about a pet hoarding TV show?

Maybe sometimes ephemera—passing thoughts, observations, lines—can do just that, can pass through a story, but maybe they can do more work too. Maybe, by finding the heat we feel within them, we can charge their meaning to get more swiftly to the subtext.

So we keep writing into the tangent, the digression, the passing fancy. Allow it to grow and claim what it wants.

Pruning, Culling, Clamoring for Light

Of course, there comes the time to cut. Not everything can stay. I think of when I read The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: I thank the idea for what it offered. It helped me see something new in the story and identify the direction forward. I allow it to move on.

Except not really. I collect all these lines that passed into the story and out again in a graveyard document. And sometimes, when I’m drafting something new, I’ll open these old graveyards and see what hands rise from the grave.

Michael Colbert is a gay writer based in Portland, Maine, where he’s at work on a novel. He’s the founding editor of The Rejoinder, and his writing appears in One Story, Esquire, and NYLON, among others. His website is http://michaeljcolbert.com/.