[wp-reading-progress-ert]

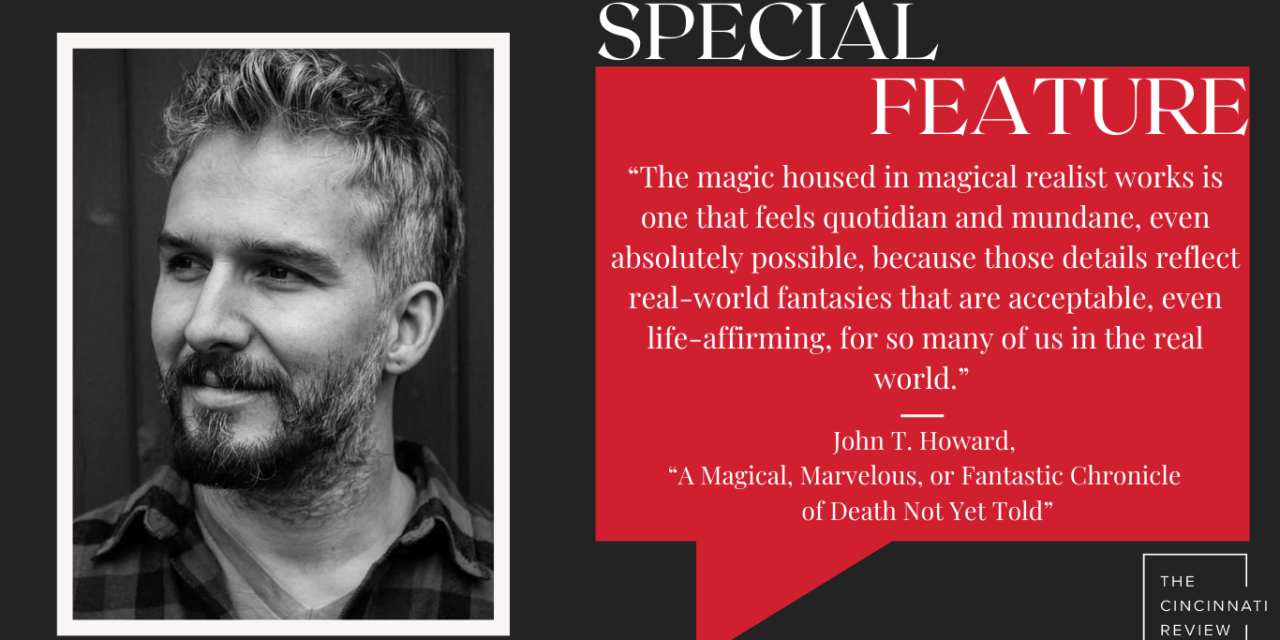

Literary Nonfiction Editor Kristen Iversen: John T. Howard’s essay, “A Magical, Marvelous, or Fantastic Chronicle of Death Not Yet Told,” is a lively intellectual adventure into the realm of family history, storytelling, religion, and cultural identity. With nods to Gabriel García Márquez, William Faulkner, Salman Rushdie, and George Orwell—just to name a few—Howard interrogates and illuminates the notion of magical realism and how it plays out in fiction and literary nonfiction—and, frankly, life itself. This is a joyful romp through a rich forest of ideas, riveting characters, and vivid details, all told in a voice both witty and compelling. Although this piece is a bit on the long side for us here at The Cincinnati Review, I flew practically breathless from one sentence to the next. And this thought will stay with me:

“A writer is capable of incredible moments through space and time. A single sentence is a time-traveling machine that can follow an infant from the earliest of hours spent in utero and then well on past that, continents away, a lifetime away, through to final gasps of breath of the same individual, some ninety years later, on their deathbed.”

Writer’s Statement: During a yearlong visiting-faculty position at Hampshire College, I had the pleasure of developing and teaching a course on the reading and writing of magical realistic work. That course, The Magic & The Real, was a hybrid literature and creative-writing class that asked our learning community to wrestle with our understanding of the term magical realism. We read primary texts together; we read scholarly interpretations together; we wrote together; we discussed our experiences with the reading and the writing, and these conversations, over the semester, helped us to evolve our understanding of the term and its relationship to other, related but different terms. These discussions—and the lively engagement of students in our learning community—inspired me to reflect on my own deeply rooted relationship to works of magical realism.

Here, I should state very clearly that, though I do write fiction, I do not consider myself to be a writer of magical realism. Nonetheless, I have, for a very long time, felt a strong personal, familial, cultural, critical, and creative connection to this particular aesthetic. These connections stem, at least initially, simply from happenstance: I was born to a Colombian mother. I have, through birth, connections to a massive Paisa family, most members of which, whether living or dead, still reside in Medellín. Beneath that simple geographic and biological coincidence, there are, I believe, other reasons to unearth.

As classes continued with students at Hampshire College, my reflection on this relationship developed through freewrites that seeded the earliest ideas for the written text before you. As the close of the semester approached, my development of this work expanded and deepened, so that the learning experience was feeding into the writing experience, allowing me to weave together various perspectives and modes of thought. From this, I created a hybrid critical and creative text that is part personal essay, part critical discussion, part family historical lore, part fiction, and (I hope) entirely at once both magical and real.

I could not have written this work without that experience at Hampshire College, and for that, I want to thank all my students from The Magic & The Real. I have come to cherish the idea of a particular term that came from our classroom discussions. The notion of something being “mundanely magical”; I can’t remember exactly which student it was who offered us this wonderful collocation of words to consider early in the semester, but that notion sat with me all spring, as it did with many students in class, given how often it came up in discussion during our weeks together. I left that class better for having heard those words uttered aloud. They were the words that led me, like a torch through darkness, to wherever it is that I now find myself, blanketed by wonder when seeking out further examples of the mundanely magical experiences that define our existence in this world.

A Magical, Marvelous, or Fantastic Chronicle of Death Not Yet Told

The cemetery where my grandfather’s body was buried sits above the city of Medellín, in the central cordillera of the northernmost stretch of the Andes Mountains. It is a small plot of land reserved for local dead, a sloping tract of mountain grasses covered here and there with walls of stacked crypts, what might be referred to as a garden mausoleum. There is a fountain structure in the center of the cemetery, with catacombs like a warren for older death dug beneath the surface. If one walks to the highest point of the cemetery, to the tiny chapel crowning the site, there are great vistas of the city sprawling below, amoeba-like arms of urban development moving outward from the center of the Aburrá Valley.

Closer in proximity, within walking distance of the dead, is the village of San Cristóbal—also referred to as La Culata due to how the village’s church was built, with its ass-end facing the nearby metropolis, these irreverent structures arguably one major center of life for the corregimiento[1] that also bears the name for the patron saint of travelers. That village was certainly the center of life for my mother’s family, even if Papa Grande and Mama Nina, my grandparents, eventually moved all seventeen of their children down from the mountains to a larger family home in El Centro, a pragmatically named barrio of the city below.

Though my grandfather’s remains have since been moved[2], those walls are still home for at least one recently dead family member, one of my mother’s eight brothers. Let’s call him Pablo. Pablo was, like so many of my uncles, quite taciturn. In fact, he may have been the quietest, most guarded of these eight men—at least for me, one of only two American-born nephews, part of a slightly larger clutch of extended family members who seldom traveled to visit with family in Colombia. It was challenging to get him and other older male members of my family to speak with me openly, candidly, dare I say even intimately.

But there was a reliable strategy for getting these close-mouthed uncles to talk a little more: the Colombian strategy of firewater. Specifically, Aguardiente Antioqueño, and—since there have been more reduced sugar and sugarless versions of Guaro—even more specifically, bottles (or cartons) of Tapa Roja, the traditional, more sugary version of anise-flavored alcohol that my uncles (and most Colombians?) throw back when indulging in drink. Think bottle service, but anywhere (and I do mean quite literally anywhere), and much more affordable. Think ouzo shooters poured into plastic copitas. Think one shot, then another, then another, until you’re feeling buzzed, then woozy, then drunk, and that’s when those tight-lipped uncles of mine will start to open up, or catcall more often, or argue, or get into fistfights with each other. That’s when things feel as if they’re blazing with life. Complicated and messy, oftentimes with unwelcome ramifications, yet still very much alive.

I have a memory of that uncle on a trip with other uncles and some cousins of mine. There must have been eight or nine of us traveling in two vehicles, a car and a large box truck, on a five- or six-hour drive to the farm of another uncle to count ganado, to tend to this and other cattle-rancher chores that this other uncle—let’s call this one Arturo—tended to every couple of weeks, very often accompanied by a few of his brothers and his brothers’ sons. Uncle Arturo’s work was not unlike that of his father, my grandfather Papa Grande, before him or of Santiago Nasar in Gabo’s[3] Chronicle of a Death Foretold, who travels to the ranch he’s inherited from his father each Monday to administer similar duties demanded of any cattle rancher in Colombia. Thus our trip to Los Monjes, the name of this particular finca of Arturo’s, located on the outskirts of a small northern city called Montería.

On this trip, a few hours north of Medellín, we stopped for lunch in some village. Perhaps in Caucasia, or La Apartada, or Planeta Rica. Wherever the stop, whenever, with my uncles, with my cousins, with a younger version of myself, it was always the hour of indulgence. This—of course—translates into drinks, since drinking is (and was) for my uncles an essential component of their working lives. In this way, they are further mirrors of their father before them: Papa Grande’s heart attacked while he was throwing back copitas of the same ubiquitous regional spirit and engaged in the business of buying and selling cattle in Medellín’s Feria de Ganados.

As we wait for our afternoon meal to be prepared, the piping hot bowls of sancocho or the plates of carne en bistec or sudado or bandejas paisas or whatever, there is the bottle of Tapa Roja that they’ve ordered, along with the administration of copitas to be filled, to be passed along, to be thrown back, by the oldest among us, by the youngest. I would have ordered a beer like I always did in my twenties, and my uncles and my cousins would have chided me for taking a sip of beer as a chaser after a shot of guaro. “El medio gringo si le gusta tomar,” they would have said, the closest of the uncles clapping me on a shoulder. “John tomas,” they would have joked, using my second name as a verb, the second-person singular present-tense conjunction for the Spanish verb “tomar,” meaning, in this case, to drink. John Thomas si tomas. Tomas y tomas y tomas, and still, the shot glass returns filled once more: I would have been woozy before eating whatever we ate, I would have been drunk after finishing the meal.

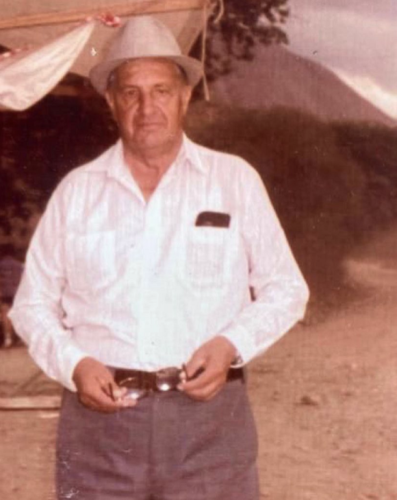

My uncle Pablo, like any among us, drank more than his fair share that afternoon. One bottle of Tapa Roja very likely bled over into a second bottle. Now: the meal has finished but we have yet to resume our journey. My cousins and I are in the back of the box truck, lounging on the truckbed, waiting for the small convoy to leave, the departure held up over some groceries that are being purchased after the meal. Sundries for two or three days at the farm. Pablo is there in the back of the truck with us, smoking Marlboro Reds, his customary cigarettes, standing over us, smiling handsomely, his sun-drenched body a beautiful brown that continues to earn him and his similarly skinned offspring the muted ire of those who are the racist contingent in my family. Somehow, we have gotten on the subject of children. Perhaps my cousins and I, all young men at the time, are talking fearfully of fatherhood as entrapment. Perhaps we are comparing notes on scares we’ve had. Perhaps we’re bullshitting about something else, something entirely unrelated. Pablo has one hand above his head so that he is holding the raised bottom lip of the open cargo door, pinning himself in place there. His gaunt face is carved with deep lines running down the center of either sunken cheek.. Our grandfather’s cleft is there like a knife wound too, cutting Pablo’s chin in half. His deep-set eyes are distant dark-brown stones.

He takes drags of his cigarette and turns to exhale out of the truck, the plumes of smoke gray yet glowing. The sun behind him is loud, an omnipresent radiance that makes my uncle little more than a cutout silhouette, a living shadow. He chuckles at something that is said, and this is when my uncle informs us, a handful of his nephews, of all his many children. “Tengo niños regados por todos lados,” he says with a laugh. He starts to point into this nameless village, down a visible street, then to other villages across these lands, to those we’ve driven through to get here, to children he has fathered all over the place. He has used the verb “regar,” which can be translated as to scatter, or to spill, or to spread.

Now that Pablo is supine and swaddled in the same wall-bound confines where my grandfather’s remains were briefly held, I wonder how many fatherless children are out there in the places he traveled to, how many nameless cousins I have, unaware of their father’s death. In Planeta Rica, perhaps. In Caucasia. Anywhere else along the way.

For those who have read Gabriel García Márquez’s magnum opus, Cien años de soledad, or the English-language translation penned by Gregory Rabassa, there may be in my own family story echoes of certain magical-realist elements. I cannot mention my grandparents’ seventeen children without thinking of the seventeen Aurelianos in Gabo’s book, each of these sons born to a different mother, each one marked for death in two ways: they all have the same name as their father, Colonel Aureliano Buendía—and they are all permanently marked by ashes from crosses drawn across their foreheads on Ash Wednesday. All seventeen of Gabo’s Aurelianos will, in time, be assassinated, simultaneously a word, fictional notion, and historical horror made—regrettably—more mundane than magical for me, given my limited understanding of Colombia’s long, complicated history of violence.

Whenever I recall my uncle standing above us in that box truck, smiling and smoking, his silhouette a sun-blazed cutout, I find myself—in this memory—set in a preternatural location not unlike Macondo, a place where there is tangible belief in levitating priests, and lachrymose (or bleeding) effigies, and ghosts who return to reside among the living, and hordes of yellow butterflies who follow individuals around like an embodiment of grief, and a fluidlike, cyclical nature to the unfurling of time, as the faults of one generation after another echo out into oblivion, until finally the last flickering sputter of life is silenced.

Macondo is a place where, not unlike other settings across the globe, the scientific names for congenital malformations of the body are often supplanted by other registers of language, by terms closer to the visceral, more heartfelt reaction of daily witness. Think vernacular or colloquial, think everyday speech. Or consider the intimacy of familial translations. My brother’s congenitally altered feet his “patoos.”[4] The words for my daughter’s limb difference[5] shifting from the cold, medical terms I’ve since forgotten to the little arm she has decided, in a brief imagination of her future self, to call Mr. Nubbins. There is in such shifts the potential for exotifying those who are born differently, the attempt to make such infrequent (yet factual) malformations magical rather than mundane and ordinary—a matter of life truly experienced outside of fictional structures.

In Cien años de soledad, for example, there is the boy born out of incest, the boy born with the tail that makes manifest his great-great-great-great-grandmother’s fears of a family curse, the curse that will come to play out, eventually, with the misfortunes of the last in the Buendía family line. Certain readers of the book, carrying within themselves certain readerly responses, will see in this curse of a tail something magical and mysterious—and yet all of us at one point in our fetal development have had tails of our own. Scholarship found at the National Library of Medicine informs me that the human embryo “has a tail with 10-12 vertebrae” that typically disappears by the eighth week of embryonic development. The morphology of a five- to six-week-old fetus reminds me of salamanders I’ve encountered turning over stones in damp forests, though researchers see similarities between the human fetus and porcine embryos. Take, for example, a study conducted recently by the Universities of Cambridge and Nottingham in which scientists “dissected whole flat discs from pig embryos at different developmental stages and found that development of these embryos matches with the observations on the in vitro human model.”

The human fetus generally reabsorbs the tail, through a process ominously called “programmed cell death,” leaving behind the coccyx or tailbone as evidence. Sometimes, when such morbid-but-necessary programming fails to occur, there is more than simply a knuckle-like remnant beneath the small of our back. Sometimes, babies do actually come into the world with a vestigial tail. Whether it’s discovered in the Brazilian city of Fortaleza, in Punjab, India, or (more recently) in the Georgetown Public Hospital in Guyana, this human tail is generally made up of fatty tissues, connective material, and slight musculature, as well as blood vessels and nerve structures. Covered in skin, it generally has no bone, no cartilage, is nothing more than a loose appendage draped from the lower back of an infant’s body. Such infrequent appearances of tails (very seldom indeed; only something like forty cases have been documented since tail documentation began in earnest) are occasionally related to spinal dysraphism, or a malformation of the spinal cord, making the unexpected appendage a visible sign of more serious underlying issues.

Such was the case with a boy born in Punjab, who was believed by many to be a living reincarnation of Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god. Until his tail was removed, the boy was visited by supplicants who hoped he might offer them blessings for such pilgrimages. This boy was born with a congenitally malformed spine, the base of which was so badly damaged that he could neither walk nor control his excrement. After the loss of his parents, an aging grandfather cared for him. There is nothing magical or exotic about the sadness one hears in the boy’s voice when, in video footage for a short documentary, he tells his audience that he is tired of being mistaken for a monkey god, that he simply wants to be a normal boy.

In Gabo’s rendition, perhaps it is the taboo of incest that makes the appearance of a human tail a magical experience for some readers. There are Úrsula Iguarán’s foreboding augurs, her fear of what curse might come from incestuous relations in the Buendía family, and the horror of such damnations reverberating through generations in a biblical fashion. Spoiler alert: That is indeed where Gabo takes readers, given the ways in which the Buendía family is swept from existence in the closing pages of the book.

Here, the mundane facts of my mother’s family return, entwined not with a love affair between an aunt (Amaranta Úrsula) and her nephew (Aureliano II, illegitimate son to Meme and Mauricio Babilonia, the mechanic who is consistently followed around by Gabo’s infamous rabble of yellow butterflies[6]), but instead with the practice of cousin marriage. Like Albert Einstein and his second wife, Elsa Lowenthal, my grandparents were first cousins who fell in love and got married. Like Queen Victoria and the first cousin she wed, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Mama Nina and Papa Grande brought a large number of children into the world, none of whom were born with any lingering remnants of a tail. This particular style of union is why my mother and her sixteen siblings all bear two identical surnames, the paternal and maternal apellidos an exact echo of the other, coming together as Maya Maya for the lot of them.

Cousin marriage has, more recently, fallen out of favor[7] in Colombia (as elsewhere, I suppose), as a practice in Latin American countries that, when scrutinized, very likely has to contend with long-lasting racist strategies for retaining white bloodlines as well as the Roman Catholic church’s prohibited degrees of consanguinity. I have no clue whether my grandparents, when they married, received dispensation from local religious authorities. Similarly, I don’t know if Maria Theresa of Spain and Louis XIV of France, double first cousins, received such allowances from a pope when their marriage was arranged to put an end to the Franco-Spanish War in the seventeenth century. I have read a word here or there about Duke Francis IV of Modena and Reggio, decades later, in the first half of the following century, who received such a dispensation to marry his niece, the Princess Maria Beatrice of Savoy, with whom he fathered four children, all born without tails, it seems. Is that historical example more or less magical than the fictional version Gabo creates?

In truth, my grandmother Mama Nina gave birth to twenty-one babies, not seventeen. Note to self: check in with someone, your mother or an aunt, to verify the number, whether it’s twenty or twenty-one. There are, within this staggering number of offspring, other details that make for a mundanely magical reading experience. Mama Nina wasn’t married until her midtwenties, and she didn’t have her first child until the late age of twenty-five. Plus: all twenty-one of these offspring were single pregnancies, not twins, nor triplets, nor anything larger in litter, and taken together over the course of her life, Mama Nina found herself with child for a little over fifteen years, the last birth occurring well into her forties.

Four of the infants died early, three so early in time I’ve never even learned their names; the last of the four was one of the first few girls born to my grandparents—let’s call this short-lived aunt of mine Luzita. The very next child, another girl, was given the very same name, so that there was a second Luz to commemorate the life of the first, fashioned as a kind of doppelgänger who, later in life, was the first of the surviving adult offspring to succumb to death. Cancer of some kind; it took one of her legs in its entirety before it took her life. Perhaps this necronym marked her for an early death, not entirely dissimilar from the ashes that marked all seventeen of Gabo’s Aurelianos; which is to say that this morbid detail about my aunts’ names is a conspicuous coincidence, one that might be read as magical by some readers.

A few decades before that loss, a set of family portraits was commissioned, in the late ’70s or early ’80s, two or three photographs of the entire family arranged in rows in the central patio of the larger home in El Centro. Think of class pictures, decades ago, you seated alongside your second- or third-grade classmates. Or think of more recent class photos of your children, arranged in neat rows with the shortest seated in front and the tallest standing in the back, the teacher off to one side, a plaque held by little hands. This is what those family portraits of ours resemble, but the oddness of our family’s class pictures is how the students—my aunts, uncles, and mother—all range in age widely, from a youngest son who is very likely no older than nine or ten to the eldest sister, already in her late twenties if not thirties by the time these photographs were taken, she perhaps a decade still from serving as a senator in the Colombian government.

The quote-unquote teachers are centrally located: Mama Nina and Papa Grande standing right smack in the middle of the back row, surrounded by their seventeen Aurelianos. Neither of my grandparents is smiling in the photographs; they both look very tired and quite old. As a recent father for a first (and perhaps only) child, in a constant state of fatigue, I can’t begin to imagine the exhaustion of rearing so many children for so many years of one’s life, even if some of the older children were, very early on, conscripted into household duties that included, of course, helping with the rearing of younger children. In a sense, the drudgery housed in those photographs feels multigenerational, a thought that brings me back to the cyclical nature of existence—at once magical and mysterious, yet familiar—found within Gabo’s world of Macondo.

Magical realism is a term that has caused much debate and disagreement. Conferences have been held to pin the term in place and to quiet the scholarly din. Note to self: Since the image of pinned butterflies lying lifeless in display cases has come to mind as you write this, you might use that in some way, perhaps in a poem. In some ways, the term is almost fishlike in its slipperiness, a notion for something that once referred to one thing in particular and finds itself in flux and in competition with other terms meant to describe similar but different aesthetic notions. That slipperiness feels almost tangible as I try to describe it: the often-documented etymology of the term, the movement of German ideas in the German language[8] into a Spanish translation that percolated through literary and artistic communities in Latin America only to end up, after a great Boom, in the hands of—among others—publishing giants in the Global North, utilized for marketing a limited share of Latin American letters for a—narrow-minded? myopic?—gringolandia readership not often enough interested in discovering works in translation.

In competition, the term has butted up against theoretical and artistic perspectives by other creative thinkers, words such as marvelous or fantastic, even occasionally bumping heads with (what might be considered) antecedents such as surreal. More recently, that butting-up process has seemed to push a collective (mis)understanding of magical realism in line with terms such as fantasy, speculative fiction, even parts of science fiction; and this without opening the floodgate of subgenres to ask if Bangsian work (or whatever else) might be related.

But what is magical realism, really? Here, I’ll parrot the Argentinian writer Fernando Sdrigotti, who in his essay, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Magical Realism,” is eager to criticize much of what the term stands for, offering up for consideration these worthwhile questions of interrogation: Is it a genre? Is it a style? Is it a literary movement? Is it some kind of aesthetic imperative, with artistic battle cries akin to André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto? Sdrigotti seems to think that the term is little more than a half-baked hot potato of an idea, a “limited” and limiting notion passed along quickly from one set of hands to the next without finding itself fully formed in a way that adequately captures a more robust understanding of the wide array of beautiful oddities one encounters when surveying the broader landscapes of Latin American letters (Is that even possible? I wonder as I write this). He quotes others critical of the term, calling it a “choke-chain” and a “magical realist imperative” while settling on the words algorithm or formula for his critical perspective, something he finds “isn’t in any way useful to explain all of the fiction” of Latin America[9]. I don’t disagree, and I certainly don’t feel as well read as I imagine Sdrigotti to be—I’m unable to offer evidence or acumen or argumentation, one way or the other.

Sdrigotti’s essay provides many worthwhile ways to interrogate our understanding of this aging term. Certainly, convincing readers the globe over that there is more to Latin American letters than this smaller subset of works and writers is a worthwhile endeavor. The time spent tracking the etymology of the term echoes other historical etymologies that preceded his essay, but still, what he provides is accurate, entertaining, and helpful for those wanting to learn more about the antecedents that have seeded our current (mis)understandings of the term. His critique of the drama series Narcos, in its conflation of (sometimes) historical (sometimes heavily fictionalized) violence with magical realism, is certainly warranted, given how Netflix’s narco-narrative “based” on the life of Pablo Escobar begins each episode with an epigraph[10] that tries to define magical realism, before erroneously stating that “magical realism was born in Colombia.” Don’t ask me to explain the purpose of using such an epigraph for a dramatic series touted as a biopic.

Perhaps most importantly, in the essay Sdrigotti offers a further refinement for our definitions of such magically real encounters in Latin American life (i.e., literature, history, culture, etc.), moving beyond a “juggling of exoticism and legibility” (note to self: this juxtaposition of terms seems to echo a definition of magical realism that Sdrigotti is very critical of later in his essay, a curious contradiction) to call out the problematic—and quite tangible—misuse of the term by publishing giants as “a practical marketing ploy, a reduction by means not of absurdity but of obfuscation—a crude simplification through fuzziness.” That Sdrigotti, in his work, is also guilty of a kind of reduction, in trying to supplant magical realism with his preferred term, “lo fantástico,” for all works of fiction one might encounter in Latin American letters past, present, and future, is beyond the realm of this essay; but perhaps it’s worth noting for those interested in continuing that aspect of the conversation. Certainly, there is something vital to acknowledge and to wrestle with in the ideas that Sdrigotti draws out of a fairly recent essay penned by another legendary practitioner of Latin American letters, the Peruvian Nobel Prize laureate, Mario Vargas Llosa.

Building off (or perhaps simply restating, or echoing) ideas found in Vargas Llosa’s essay “Sirenas en el Amazonas,” Sdrigotti argues that the whole of Latin American literature is defined by the “violent and contrasting nature” of European worldviews clashing with indigenous perspectives in the Americas during the age of conquest—what Lâle Davidson, an American writer and professor, describes as “the intersection of competing definitions of reality.” I prefer the word confluence over intersection. That bloody confluence of drastically different worldviews, Sdrigotti also asserts, is infused with a “[fantastical] element [that] was available to pre-Columbian cultures.” Reading that, I have to ask myself how Sdrigotti might define the contrasting nature of such bloody exploits further north in lands pillaged (though under different models of exploit) by Belgium, France, and England, during the colonial age.

Lâle Davidson, to her credit, recognizes a broader geographic footprint for such violence—and subsequently, for similar strains of literary work born out of the wrestling with and against of such violent tendencies, allowing Davidson the ability to welcome Toni Morrison, Leslie Marmon Silko, even Karen Russell into the folds of magical realist writers; she is not alone in expanding magical realism’s original geographic footprint. With such an expansion in mind, I have to ask myself what might be Sdrigotti’s take on indigenous populations native to what is now referred to as North America, where there were once vast tribes of varying cultures, each with their own rich set of belief systems, any one of which we might describe as something quite different from the European model of reality, all of which were exotified, illegitimized, and nearly eradicated through the barbaric (and xenophobic) efforts to erase such “fantastical elements” from the “new” world. As if that “uncivilized” continent were a blank canvas not yet written upon, real, magical, or otherwise, free of such barbaric confluences, or intersections, or worse.

And yet Sdrigotti’s “lo fantástico” seems to be solely, for this Argentinean writer, European exploitation regionally sequestered to the central, southern, and Caribbean areas of the Americas. Side note: What do we make of less fantastical Latin American literary movements that need to be housed in the same categorical home? For example, costumbrismo, in Colombia, as one such countering blip. Here, I find myself nodding in agreement with Sdrigotti’s earlier point criticizing the limited scope of the term we’ve put under microscope. Here, I find myself once again wondering if such a task is even feasible. Or helpful—should we pin magical realism into place at all?

Quick aside having to do, briefly, with Peru: Another one of my aunts married a Peruvian man and settled in Lima, where she raised her sons, two of some 40–50+ first cousins I have on this side of the family. She, my mother, and the doppelgänger Luz were the only three of the seventeen siblings to emigrate out of Colombia. My mother to the northern Americas after marrying a gringo, my Brooklyn-born and Long Island–raised father. My other aunt went to Spain and other European countries after marrying a Guatemalan diplomat. This detail about family relocations is mundane enough to be easily forgettable—unless you witness one of the three or four family-portrait variations that were taken that day when my mother’s family was photographed in its entirety in the late 1970s or early ’80s.

The setting for all of these portraiture variations is, as I’ve mentioned, the home’s large centrally located open-air courtyard. I recognize the colorful pattern of tilework from my visits to that space as a child, before my grandfather’s death, before most of the marriages that would leave my aging grandmother, Mama Nina, living into her nineties in a smaller apartment in the barrio of Laureles with her two eldest daughters, the two that never married. The children and their parents are arranged in two rows, and behind them is one of the courtyard’s brightly lit walls, along with drapery covering a window that leads through that wall into the large home’s small television room, all of this backdrop ablaze from the sun overhead. But there is darkness there in the background too. To one side, there is a dark windowless hallway that recedes into the background, a hallway that leads out to the front door of the home in El Centro de Medellín.

In one variation of this image, the three sisters who left the family for lives outside Colombia are the only three figures (out of nineteen) who are framed in that dark rectangle of shadow created by the receding hallway. The rest of the family is framed by the bright blaze of the wall and drapery behind them. They remain in that Colombian home, so to speak, while the other three have long since departed, the first to have moved out through that windowless hall for good. That posed arrangement predates their departures, but since then it has become a detail often talked about in our family as a curious moment, an almost magical one, something mundane made to feel preternatural, an unexplained curiosity that resides alongside what we understand to be certain and solid, a bit of family lore, something that augured their departures, these three sisters, the only siblings who would depart for distant shores outside the borders of their Colombian birthplace, as if the image itself were a detail to be found in the pages of a magical realist work.

Magical realism was not born in Colombia. Sdrigotti is correct to mention this when he criticizes not just the showrunners for Narcos but also the Colombian Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism, specifically for a global tourism campaign from the 2010s that ran a variety of different advertisements with the slogan “Colombia is Magical Realism.” The ads aren’t memorable; they are poorly scripted, poorly acted exotifications of Colombian locales by gringo tourists, what Sdrigotti calls “vomit-inducing short clips inviting visitors to the country.” Some of them have poorly rendered special effects with flurries of floating text that call to mind hordes of locusts or other winged insects moving through the air, all of that textual material quoted from Colombia’s most beloved (and, perhaps, most despised; the jury may still be out on this)[11] Nobel Prize laureate. No, magical realism was not born there, but in Germany, coined as an unrelated term even before the translated Franz Roh text that came to influence Latin American letters in various ways. And yet, perhaps, for a larger swarm of readers the world over, the term has been cemented into place by the Latin American Boom of the 1960s.

Many might argue that Gabo’s Cien años de soledad helped to pin the term in place for a wider audience, moving it out of the mouths of academics into a larger, globally reaching zeitgeist following that Boom. Side note: Can the Earth’s residents, at any one point in history, be understood to reside within a singular zeitgeist? That feels as limiting as the limits intended by this pinned butterfly of a term. Let’s put forward that argument here: For broader readers, the world over, it may very likely have been the many translations of Cien años de soledad—which I’m told by sources on Wikipedia has been translated into forty-six languages and sold more than fifty million copies worldwide, making it one of the twenty-most widely published books of all time—that introduced such a massive audience to this, what shall we call it, a movement? A style? A genre? An aesthetic imperative? An author? A set of authors? A people? A country? A set of countries with similarities to confound their differences? A differing perspective? Any number of people who adhere to such a worldview?

Sdrigotti argues that it is the academic scholarship of Angel Flores, and in particular, some problematic five to ten pages published in 1955, that have created the rippling-out challenges still arising with magical realism’s stranglehold on Latin American letters; or so Sdrigotti would have us believe with his heavy critique of Flores’s work. But how many people have read Flores’s essay? To claim that this was the work that cemented the term in place seems like exaggeration to me; to be fair, Sdrigotti was putting forward the argument that Flores’s work cemented the term into place for academic circles. My thought, obvious as it may be, is that term has long since traveled beyond the small and insular spaces of such academic circles. Through such travels, crossing beyond borders of culture and language, the term has been ever-changing, evolving, expanding its geographic reach and footprint, while still finding itself linked, consequentially, to some of its most widely read earliest examples. So that magical realist work can now be found not just in the work of Global South authors but practically anywhere and everywhere. In Tokyo, in London, in any number of apartments in any of the five boroughs of New York City, including Queens, of course, where Angel Flores seems to have penned his 1955 essay, though not in Jackson Heights. How do I know this last bit of minutiae? Don’t ask me—I’ve long since forgotten where that tidbit came from. Or maybe I’m simply making it up.

“Colombia is Magical Realism,” the ads proclaim, asking the audience to see in this statement something worth seeing, something powerful enough to draw the viewer from their home across the globe to experience the magical nature of the country firsthand. I’m struck by how Sdrigotti calls these ads “vomit-inducing.” They aren’t great ads, but what is it about them that makes them emetic? Watching them, I recognize that my mother’s birthplace is trying to profit off the profitability of this evolving, catchall term. By profit, I mean that these ads may be trying to help people within the country make a living, survive. By that, I also mean that the country, through this campaign, is working to move past its long and continued history of violence, to paint for outsiders a different picture. By using the term in this way, I assume that the country is also, perhaps, trying to reclaim the language from publishing industry giants in the Global North, to dredge up, as I’m suggesting, much-needed tourism in a country that has, it bears repeating, for many years, been marred by various forms of violence (e.g., civil wars, narco-driven violence, etc.).

But Colombia, like any place on earth, is not just its history of violence. Just like the United States is not just its abhorrent history of slavery or, more recently, its unrelenting history of unchecked gun violence or its resurging xenophobic MAGA isolationist movement echoing, in propaganda and practice, German fascists from the preceding century. Yet for Colombia and Colombians, Violence (with a capital ‘V’) is often the single narrative that gets broadcast to outsiders looking in—and more specifically, drug violence, given the proliferation of narco-narratives throughout Hollywood and elsewhere. Colombia and Colombians, for some time, have been trying to overcome the reductive labels and hateful epithets slung about so easily by anyone who assumes that the country is nothing more than the sum productive of one narco-narrative after another. Narcos a few years ago. The new show about Griselda Blanco that’s out now for easy, bingeable consumption on our most bingeable of content outlets, Netflix. Along with countless other examples that have captivated gringo audiences for decades now[12]. Last night, for example, in conversation with a well-educated and well-intentioned fifty-something-year-old, I heard (not for the first time) that his understanding of Colombia and Colombians came from the stereotypes found in the episodes of the earliest rendition of Miami Vice, which in turn were created from real-life experiences impacting gringos (and Latinx residents) in Florida in the ’80s and ’90s, perhaps even earlier.

photo via Kirk Siang at Flickr

The reality of the situation is even more complicated than those complications suggest. Sdrigotti, in his criticism of that tourism campaign, quotes one of the gringo visitors, who says, “When you arrive here [in Colombia] it’s like you’re entering a García Márquez novel.” Sdrigotti’s disgust for the ads seems to be anchored in a perceived reliance by the advertisers on a particular kind of fiction (i.e., magic realism) as a stand-in for various facets of Colombian life, culture, history, reality, etc. The fact is that Colombia has housed beautiful things and violent things all at once, and that there are aspects of Colombian life very much like the magical or marvelous moments encountered in novels such as One Hundred Years of Solitude or Love in the Time of Cholera or Chronicle of a Death Foretold, even moments of violence reminiscent of scenes encountered in episodes of Narcos.

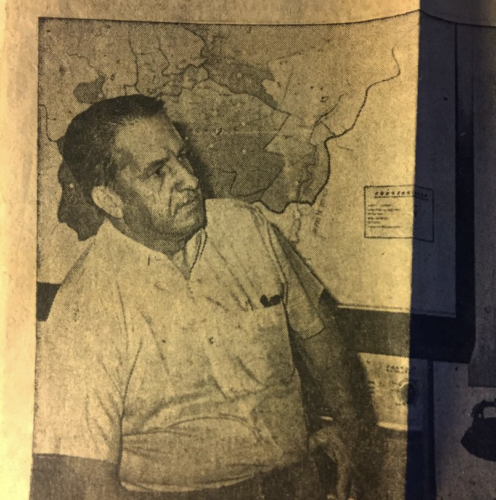

I think of the bombings that my uncles survived. I think of how many times one uncle was stabbed, the watch that was ripped off his wrist, the poor street children desperate enough to engage in senseless violence for a paltry bread-buying trinket. I read over yellowing newspaper-article clippings that detail the time when Papa Grande was kidnapped alongside a socio of his while these two ranchers were out in the fields counting ganado. I recall what I witnessed when I saw that same grandfather’s remains pulled from the wall of that cemetery five years after his death, the skull bright red, insects the size of swallows fleeing from within the tomb, how all of it feels absolutely magical, even if it is all attached to historical fact. I think of the weddings I’ve been to, their size and other abundances. The funeral masses bursting with many hundreds of mourners. The churches I’ve walked through, built to shun one colonial-esque metropolis over another a century ago, simply because of the orientation of their front door, their ass end, when different cities were competing to see which regional center of life would dominate.

There is nothing, in my mind, emetic in these efforts to share such a worldview with others, so that a country and its people might have within them the ability to build upward and outward a more welcoming appearance, no matter how poorly created those advertisements may be. No matter if there are gringo tourists coming like a plague of locusts to devour whatever they can, so long as they bring plenty of greenbacks to be able to pay for that insatiable hunger of theirs. All to encounter the magically real experiences promised in that vomit-inducing ad campaign. All to convince outsiders of the stability needed to encourage such visits.

Many people in the Global North like to imagine that we—far from the turmoil of Global South nations—live in a rational and stable society, one that isn’t hindered by superstitious or delusional beliefs that might be labeled fantastic or outlandish by outside perspectives. That perceived stability is accompanied by the notion that our system of governance is a functioning and reliable one: our nations are run by some entity of citizens who are freely elected, empowered by the people to serve as a governing body that makes, carries out, and assesses laws while administrating and regulating various other aspects of society. Our governing bodies maintain roads and service other necessary elements of infrastructure. They develop and implement systems of taxation to fund a reliable postal service, military, police force, fire department, and whatever else is needed to manage the needs of the people. They regulate, maintain, and work to strengthen various aspects of the economy. They serve as conflict control, both within and beyond the country’s borders. And they adapt rules, regulations, and policies as needed, in the hope of running an orderly society, one governed by logic and the laws of the land. Along with this belief in functioning government systems, there is the widespread perception that Global North nations are reliably safe places, free of turmoil, free of violence, free of strife. Free of what David Lodge calls, in The Art of Fiction, the “great historical convulsions” that define Latin American literature.

These beliefs are a delusion, one that requires either ignorance, willful blindness, or some other set of deplorable defining personal characteristics, to look at the current state of affairs in our own backyard and then put forward the perspective that we live in a place, time, and society that is free of such growing political strife.

Since we’re essentially already on the subject, let’s return to the United States of America, again, as an example. The internet tells me there are some seventy-one million Catholics within US borders, the largest population of Christians in our ranks. If we take the Catholic Credo for its word(s), as I take my mother for her word, there are notions that Catholics believe to be irrefutable truth. Let’s start with transubstantiation: Catholics, when they go to church, when they take part in the sacrament of Eucharist, believe that they are eating the flesh and blood of Christ. Beyond this emetic idea of church-sanctioned cannibalism, there’s also a belief in the possibility of returning from death: Catholics, along with other Christian denominations and Protestants[13] the world over, do indeed believe in the Resurrection of Christ. And in his ascension to heaven. Thus the global importance of Holy Week and Easter Sunday celebrations.

That number of believers drops a bit, or is muddied in various ways, when you start to consider reverence for Mary. Catholics believe in both an Immaculate Conception and in a Virgin Birth, similar but different conceptions of uterine life without need of any man or the acts of copulation needed for procreation. Protestant beliefs on these vary, a sort of spectrum of sorts, that, in its most irreverent form, labels such Catholic fancies as Mariolatry, a portmanteau of Mary and idolatry that should never be confused with Mariology. Included in Catholic reverence is the notion that the most revered mother made her way into heaven both body and soul. Whether she fell asleep or died a more gruesome human death, most followers of the various houses of Christ will say they believe that Mary is in fact in heaven, alongside her son, alongside an Almighty Himself.

For anyone who considers themselves an atheist, perhaps even certain folks who would label themselves as agnostic, any of this may come off sounding like poppycock superstitions, the kind of preternatural nonsense people of a certain ilk need in order to be able to wrestle with human conceptions of death and of the darkness that comes after that natural expiration of life. In the US, there seems to be a kind of arrogance at work, embracing these variations of belief systems as acceptable, while othering others that fall beyond two of the three arms of the Abrahamic traditions. Or by simply othering Christians and Catholics that come from Global South nations.

The myopic nature of Global North arrogance extends to history and violence as well. In the United States, there is also a willful blindness (or worse, a calculated choice) to not acknowledge our shared history, a complicated stretch of violence that begins with the original sin of slavery and continues through the Jim Crow era into the tumultuous years of the civil rights movement and on to today, to a post–BLM movement era replete with continued violence, ever-worsening political strife, and the disrepair of aging infrastructure that in itself points to racist practices of structural development. To call out the instability in Zimbabwe or Ecuador without looking honestly at the xenophobic tendencies being espoused by MAGA hordes looking to protect the boundaries of whiteness (let alone the willingness to storm the Capitol, to violently disrupt our democratic practices to retain one tribe’s presidential power after very clearly losing an election), is both arrogance and hypocrisy. To criticize the infrastructure of Honduras when even the White House is providing data[14] to point out how poorly neglected US infrastructure remains, while still calling our country a shining city on the hill—this is also arrogant, perhaps even politically foolish: consider that fixing potholes may help ensure one’s success in getting reelected to public office.

And yet so many people across this land see the USA as being better in some way: a safer, more organized land, one of opportunity, a place capable of providing stability and promise for its citizenry. But that land is more and more skeptical of unfamiliar forms of magic as it becomes more and more skeptical of the idea that this country is—has always been—a blending of world cultures. A confluence oftentimes violent, as it was at the very start, when colonial expeditions came with the notion of pushing out into new spaces, pushing and pushing and pushing, until the horrors of a destiny manifested in such continued exploitation, initially accomplished by a long, bloody march west. That manifest destiny was defined by the urge to erase any darker antecedents. That urge to erase became the status quo of racial inequality. Today, that urge is defined by a growing willingness to push against such differences, to eradicate them, all in order to protect an ever more secluded notion of whiteness.

That myopic and bigoted set of beliefs about our shared reality extends, of course, to a collective judgment of literature that arises from “third-world” nations in the Global South. Anything magical or preternatural that arises in the writing of those outside our boundaries must be labeled as different or exotic, even if, in all practical terms, some of those “magical” events may in fact echo many of the beliefs American citizens hold to be most important for themselves, some beliefs so important they are turned to for making monumental decisions about people’s lives. It is as if the American people have grown blind to the preternatural notions they so eagerly cling to with their varied religious belief systems.

Even here in the United States, where more and more people are growing more and more wary of magical perspectives, I have witnessed magic akin to the kind Gabo describes in his work. Not simply in the writing I read but in my daily experience with the really real world. Living on the West Coast, I have traveled to coastal forests during high points of monarch butterfly migration, to encounter trees covered in the thousands by these colorful insects. I have watched the species of black bird (whose name I forget) that has learned to eat the poisonous butterflies, as they dive into branches, producing explosions of butterflies bounding outward. I have hiked the Methuselah Grove of bristlecone pine in the White Mountains of California and placed my hands on the trunks of trees many thousand years old, older in fact than any historical Christ figure, and stood in awe of these still-living evergreens. I have been in the foothills outside of the Berkshires in Massachusetts, where I was witness to countless numbers of ladybugs coming together for whatever reason, the sheer number and ubiquitous nature of their experience quite magical for me to experience, given how unfamiliar and odd it felt, even if we humans congregate in similar size groupings across the globe.

For the dendrologist, the near-geologic age of certain trees isn’t at all magical. For the entomologists among us, there are certainly scientific terms or field-specific jargon to codify and explain, in language and logic, such marvelous mysteries as I’ve witnessed. I can only imagine the arboreal and insect worlds of my mother’s Colombia having similar magical qualities when witnessed by anyone with a creative mind, especially by a writer who might take, for example, a particular butterfly species’ penchant for a certain perfume and twist that detail into something a little magical, evident in the wondrous work done to attach such vivid descriptions of the insect world to character development, especially in a novel filled with hundreds of characters who need distinguishing characteristics. Out of such creative wells, the yellow butterflies propagate onto the page. They flitter and fly, they overwhelm the imagination.

Not far from my current residence in Eastern Massachusetts, there is a shrine to Our Lady of La Salette, where I take my Catholic mother often to light votive candles at five dollars a pop, hoping that the Marian apparition might offer us blessings and good tidings. Not all that different from an Indian boy born with a tail, and yet quite different, given that the Indian boy is confirmed by doctors, on film, to have suffered a well-documented human difference that has nothing to do with celestial beings. What evidence do we have to confirm what Mélanie Calvat and Maximin Giraud, the two shepherds, said that they witnessed on mountain slopes near the French village of La Salette-Fallavaux? Stories? A harmonization of those two stories? Passed down from September 19, 1846, through to today, it might strike some as fanciful religious thinking more in line with human perspectives of that century. (To me, it sounds oddly similar to Colombia’s marketing campaign, something akin to “La Salette-Fallavaux is Magically Pious.”)

There is nothing odd about the French seers for my mother. She believes in this apparition of Mary as if the stories were as tangible as her own flesh. She has absolutely no doubt in the veracity of what those children witnessed a century ago. How many other countless millions across the globe share this vision of the world? Of that vast number of devotees, how many of them are natural-born citizens of the ol’ US of A? My mother is certainly not alone, not on the fantastic North Shore of Long Island, where she’s lived for nearly half a century now, nor when she visits for a wintry spell in the magical realm of New England, to spend time indoctrinating her grandchildren.

Back to literature: Perhaps the distinction between fantasy and magical realism has less to do with the content of such books themselves and more to do with what one might encounter in the real world. In the real world, there are people and cultures (and further broken down, subcultures) who wholeheartedly believe in things that might be described as extraordinary or preternatural by others. My mother, raised in a Catholic Colombian family, speaks of those Marian apparitions and other fantasies, such as the appearance of stigmata on effigies, as if these spectral occurrences were quantifiable fact, as natural to her as rain or the rising of the sun each day. She believes in the healing powers of holy water and the notion of transubstantiation. She is, it bears repeating, certainly not alone in these beliefs. If she discusses such fantastic ideas in public, she is not shunned by countless numbers in the communities where she now resides, splitting time, as mentioned, between Long Island and our current family residences in Eastern Massachusetts. She is, with those other seventy-one million American Catholics, among many others who share her idiosyncratic vision of reality.

She, with my father, was also a devoted fan of the HBO show Game of Thrones, based on A Song of Ice and Fire series penned by George R. R. Martin, a fantasy series that may arguably have drawn inspiration from the fifteenth-century violence that swept through England during the Wars of the Roses. There are, in Martin’s books and in the rendition found in the HBO series, preternatural aspects of life that very few, if any, individuals out there in the real world would truly believe to exist. Put aside for a second culturally specific beliefs in certain creatures, or other smaller subcultural beliefs in certain practices, and we may get consensus on the idea/argument that there are no dragons, white walkers, or fire-god magic in the real world. Viewers such as my parents, such as myself, such as millions of watchers the world over (forty-four million over the course of its streaming existence, which sounds similar to the number of published translations of Cien años de soledad out there) will embrace a willing suspension of disbelief, entering into a contract of “complicity”—to use a perspective offered, once again, by the writer Lâle Davidson, a notion that she develops when turning to Tzvetan Todorov’s contention that such a work of fantasy “imposes absolute closure,” creating an “enclosed reality”; this last quote is Davidson’s words again.

Such enclosed realities are understood to contain elements that do not exist in the real world. We are complicit in understanding the impossibility of these flights of fiction. In fact, if anyone over the age of, say, fifteen (even this feels too old) were to say they truly believed in the notion of dragons, anyone in earshot might be alarmed enough to wonder if the speaker needs mental-health support. Herein lies the great difference: Comparing beliefs that exist in the real world with those that don’t enables us to distinguish between magical realism and pure fantasy. The magic housed in magical realist works is one that feels quotidian and mundane, even absolutely possible, because those details reflect real-world fantasies that are acceptable, even life-affirming, for so many of us in the real world.

In addition, magical realist curiosities are couched in literary worlds that very clearly mirror or stand for our own understanding of the real world. Macondo, an offshoot of Gabo’s childhood home, lived experiences, and the influence of William Faulkner, is no less a fictional location than Yoknapatawpha County, yet it might very well be a region set somewhere within the boundaries of the real-to-life country of Colombia. None less than Salman Rushdie has put forward such a perspective, when writing that the magical realistic imagination of García Márquez “is used to enrich reality, not to escape from it,” so that “the real, by the addition of the magical, actually gains in dramatic and emotional force. It becomes more real, not less.” Giving Macondo, as Rushdie argues, “deep roots in the real” Colombian experience, just as Faulkner’s fictional county is rooted in a real-to-life Mississippi from a particular point in history, so much so that it might now be thought of as the southern state’s eighty-third county.

Westeros, on the other hand, could never be seen as a rendition of anywhere in our world. Even if George R. R. Martin remixed years of European monarchical violence in easily recognizable ways, to create a fantasy that houses dramatic representations of power struggles like those playing out in global affairs today, we, the watchers of such shows and the readers of such books, recognize such settings as fantastical. This is the fundamental difference between these two categories of fiction, a difference that then provides a kind of footprint or cartography[15] that might be helpful to categorize any single work, placing it within the realm of fantasy or within another realm that exists closer to home, as a magical realist work. The footprint for magical realism has evolved as the term has, with travel across the globe, evolved, so that it no longer simply stands for works of a certain kind being generated by writers in Latin America, though Salman Rushdie would have us believe the latter, even after having been labeled by so many as a magical realist himself. Side note: Find examples of critics labeling him a magical realist writer; find evidence of Rushdie himself, perhaps, speaking of his own work in that vein.

Leaving lands such as Westeros behind us, in different realms, so to speak, where does that leave us with our understanding of magical realism, let alone reality itself? If—like Sdrigotti—I am inclined to abandon the term, perhaps even to chronicle its death, this inclination has less to do with the evolution and overwhelming variance of adaptions we’ve seen of the term, and much more to do with my belief in writing itself as magic. I wholeheartedly believe that our tool of written communication serves as a kind of magic enabling us to capture and reflect upon reality. Here, I agree with a Canadian novelist, Jon Evans, who says that “all fiction is fantasy, it’s just a matter of degree.” Though I’d replace that word fantasy with something a little more magical in tone or diction. All writing houses within it opportunities for such magical thinking.

Writing words down has always struck me as a magical endeavor, filled with potential and kinetic energies that enable the mind to move in all directions at once. The writer, writing whatever they choose to write, in whatever style they choose, is capable of making a dream manifest. Not a dream dream, but a John Gardner–esque understanding of any story as a dream the reader experiences as reality through the process of uninterrupted reading. Think: the last five or ten minutes of the first Matrix movie, when Neo can see through the vivid experience of his digital prison and recognize that the entire world is created from encoded zeros and ones, nothing more than the binary used to define and delineate every single sight, smell, or sound. Even in the most realistic of modes, the writer is engaging in this magical enterprise simply by turning our coding system for collective comprehension and communication (language) into something that comes alive in the mind of the reader.

Characterization, description, world-building, imagery, and poetic invention, however concocted, are part of a magical enterprise for me. And yet it is all very much real, because I believe there is in that magical corpus of varied genres and storycraft techniques a quintessential attachment to the human experience, even if the subgenre shifts to fable or fantasy, even with Orwell’s talking pigs, which, I am sad to say, seem more and more very much like my neighbors down the street touting their Confederate flags and going on and on about a stolen election.

In addition, through the magical powers of the line or the sentence, the writer is capable of incredible movements through space and time. A single sentence is a time-traveling machine that can follow an infant from the earliest of hours spent in utero and then well on past that, continents away, a lifetime away, through to final gasps of breath of the same individual, some ninety years later, on their deathbed. One such fine example of this temporal form of realistic prestidigitation is found in the very opening sentence of Gabo’s masterpiece, Cien años de soledad:

“Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo.”

In Rabassa’s translation, the non-Spanish reader encounters the same magical experience, rendered in the English language:

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

Why do I call this line of language—this written sentence—a form of realistic prestidigitation? Why is it the epitome of the magically real for me? That line mirrors the capability of the human mind, of thought itself, of the ability of a single thinker to create the secret miracle of traveling through time with the cognitive powers of memory (variant and deficient as such powers can be), to recall the past, to bring the past into the present, and even, in what seems like a single sentence of thought, to string that memory along, so that it echoes out through a lifetime of eternities, with anything else the memory may come into contact.

Talk about frisson: To look at memories as if they were a seashell being picked up on the beach, for inspection of that glimmering, mysterious artifact of death, and to hear within the shell’s deepest center something living still, the roiling of that which exists and does not exist all at once. To attach that seashell to whatever else comes to mind, with another version of such magical capabilities that Borges detailed in his story about the aleph. To go anywhere, to see anything, and to bring that all together, so that it might be cradled at once in the smallest of spaces. And then to pin it in place, to share with others, through written language. Whether it’s a poem or a piece of flash; a sentence, a line, a paragraph; a short story, a novella, a novel edging into thousands of pages.

There is magic too in putting that swirling kaleidoscope of possibilities down onto the page with a temporality similar to that of lapidary. Which is to say: linear, cyclical, and a single point in time all at once. What could be more magical than the ability to mirror such a beautiful human miracle? It bears repeating: the magic of pinning such perspectives in place, to pin that form of magic onto the page for others to admire, to strive for, to hope to visit, to want to reside within—nothing seems more magically real to me than that.

Which brings me to my final point—

Many years after my grandfather’s remains were exhumed from that cemetery, one of his living sons texted me a response, providing me answers to the questions I’d sent him a little while earlier on WhatsApp: his father’s full name was Samuel de Jesús Maya Morales, and he was born in the village of San Cristóbal on March 19, 1915, the same village where he married his cousin, María Adelina Maya Sierra; the same stretch of land that cradled him in life as he remains in death, where over the next twenty-odd years, he and his wife brought twenty-one children into the light of the world, christening these newcomers with the following names in the following order: María Victoria, María Eugenia, Teresita, María Teresa, Olga Luz, Samuel Darío, Juan Enrique, Jorge Ivan, Elizabeth de la Santísima Trinidad, Jaime Augusto, Alvaro Pío, Gloria María, Gabriela María, Amalia María, Néstor Raúl, José Rodrigo, and Gabriel Ricardo; the other three babies are nameless for me still, even after receiving this message from my uncle.

Papa Grande, as I came to know him, lived until the age of seventy-two, when his heart gave out on December 5, 1987, while he was at work, throwing back copitas of aguardiente while bargaining for a cheaper price on feeder calves on a day of the year that was also my mother’s birthday, the day right before she gave birth to a third son of her own, my youngest sibling, a boy whose name and skin my grandfather, in dying so soon, would never come to know, not with the heft of his hands, nor with the organ of his voice.

Some years from now, I’ll revisit an echo of this grim experience, when I return to San Cristóbal to see the past play out in the future once more, when with the dead son, my uncle Pablo, who lingers in memories of mine like a sun-filled specter, in a present moment lying before us, we will come together as a family to watch the cemetery workers pull the remains of one of our dearly departed into the light of the world in much the same fashion. May it be a marvelous day, full of sunshine and wonder. May it be fantastic. May it be magical. May it be all these things at once. May it be none of them at all.

[1] Medellín has five corregimientos, or rural subdivisions, beyond the outer limits of the city’s urban core. That central area is comprised of zones, communes, and barrios: six large zones are made up of sixteen communes, and within those communes, there are a total of 249 smaller barrios, or neighborhoods.

[2] By moved, I mean exhumed: exhumation as a practice of “grave recycling” has, for Colombians, been what anthropologist and Latin American deathscape scholar Christien Klaufus claims is needed when rapid urbanization runs concurrent to an overwhelming surge in mortality rates. “In Colombia,” Klaufus explains in one of many articles on Colombian deathscapes she’s authored, “ordinary graves are exhumed after four years,” after which, “Decomposed remains may be stored in an ossuary, but Colombian law instructs that undecomposed remains be cremated for sanitary reasons.” These “repeated confrontations with death” square with what I’ve witnessed.

[3] Love him or hate him, Colombians have this nickname they turn to (or an even further diminutive, Gabito) when referring to Gabriel García Márquez.

[4] After enduring amniotic band syndrome, he was born missing sections off the front of all his toes.

[5] She overcame an unnamed trauma in utero that took nearly half her left arm.

[6] In 2006 or 2007, hundreds of yellow butterfly cutouts fell onto Gabo’s head when he was celebrated in Colombia for his literary achievements. A Colombian professor of mine was at the celebration. As I had been working with this professor on a senior thesis related to Gabo’s work, she gifted me one of these paper butterflies; it resides, ever since, within the pages of my copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

[7] It should be noted that I am not, herein, trying to argue for the acceptance, embrace, or resurgence of such a practice. Certainly not after seeing the colorful sequence of jokes that John Oliver, in a recent Boeing-focused episode of Last Week Tonight, made about former Boeing CEO Philip M. Condit because of his marriage to a first cousin. Still, I must admit, I was for a time enamored by one of my own first cousins. Enamored enough to write that cousin at least one love letter on one of my infrequent visits down to Medellín, where the practice was not (entirely) shunned by my family.

[8] Beyond the Germanic shift from philosophy to the study of paintings, there is an additional early-twentieth-century emergence of the term by way of Italy, though more scholarly work might be done to trace the journey of the Italian variant through translation practices to the Americas. What am I saying? There are very likely reams of scholarly work to speak to this. Perhaps more work is needed beyond the hermetic spaces of scholarship, to share news of this Italian variant with a wider readership.

[9] In a similar vein, in a recent book titled Magical / Realism: Essays on Music, Memory, Fantasy, and Borders, the poet and scholar Vanessa Angélica Villarreal refers to magical realism as “an industry standard” that serves as a “generalizing force that overlooks writers who don’t fit its mold.” In that book, in the few places where Villarreal deals head-on with her own aversion to magical realism, she works comparatively to position magical realism as a “world-breaking” genre indicative of certain unflattering perspectives foisted upon Global South literature, as opposed to its counterpoint, what Villarreal labels the “world-building” privileged in Global North modes of traditional fantasy.

[10] Villarreal, in her recent book, also offers a critique of this epigraph, putting forward three compelling points:

1) She doesn’t believe accuracy to be the aim but argues that the epigraph is instead designed to invoke “clear associations” with Latinx themes for a myopic North American audience, so that “Latin America, Escobar, cocaine, violence, drug wars = magical realism”; 2) the othering effect of the narconarrative is a dehumanizing tool with historical connections to “CIA interventions responsible for destabilizing the region”; and 3) not completely understanding the showrunners use of the quote, she hazards “that [perhaps] in the American imagination, magical realism includes the narcodrama.”

[11] Colombia has only two Nobel laureates, and they both have detractors: Gabo, who won for Literature in 1982, is often criticized for his left-leaning political tendencies and friendships (e.g., Fidel Castro), as well as his abandonment of the patria to resettle in Europe and Mexico at various points in his life; Juan Manuel Santos Calderón is—some might argue—a more divisive figure in Colombia given his work to engage with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) during the most recent Colombian peace process. That peace plan, which sought to end more than half a century of civil war, was the reason for Santos’ reception of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize and is hotly contested by huge swaths of Colombians, given the layered hornets’ nests of complications before, during, and after the conclusion of those peace efforts.

[12] It should be mentioned that such narco-narratives have also continued to captivate audiences in Colombia, so this predilection for reiterations of the same violent story cannot simply be seen as a penchant for othering enacted solely by audience members outside the culture. This process—and the critique of such a process—is complicated by this continued penchant for such violent narratives within the country as well. Here, comparative cultural work might seek out a deeper understanding of this, exploring the nuances of why such different audiences seek out such similar narratives. And arguably, such stereotypical, singularly driven narratives.

[13] Double the number of Catholics in the USA to get the number of Protestants found across the country, some 140 million people out of our combined population of 330+ million; nearly half of the American citizenry.

[14] Bridges crumbling, roads cratered, railways with antiquated systems leading to derailments of trains laden with toxic materials such as the East Palestine disaster, lead pipes leading to more Flint, Michigan–like calamities, etc., etc.

[15] Another essay I have yet to write builds beyond this cartography—inspired by recent discussions with Hampshire College students and utilizing one writer’s notion of a spectrum as a starting point—to develop a more effective X-Y-Z graph (i.e., Cartesian coordinate system) that might be well suited for categorizing the relationship of magical realist works to works that fall within other related genres or styles of literary production.

John T. Howard is a Colombian American writer, translator, and educator. He has served as Writer-in-Residence at Wellspring House Retreat and holds an MFA in creative writing from Indiana University. His poetry can be found at Salamander, Notre Dame Review, PANK, South Carolina Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and elsewhere. He is at work on a first book of poems and a first collection of essays.

He also publishes fiction as Thomas Maya; his short stories can be found in Witness, Wisconsin Review, Saranac Review, and elsewhere. He is, as Thomas, also at work on a novel and a collection of short stories. He can be found photographing his daughter, his dog, and various moments of the mundanely magical here: @jthowlard