Because of China’s nature, there is a high possibility of conflict.

—Chen Po-Wei, Taiwanese lawmaker quoted in the New York Times, July 1, 2020

It used to be my day off, July 1. I would rise early, maybe hit the gym or meet my hiking partner for a walk through the New Territories at sunrise. Luxuriate in the empty trains of the Mass Transit Railway and buses that ran on time. By afternoon it was back to my rooftop room and solitude, before crowds thronged the harborside for the annual fireworks display.

Or did I? Who truly recalls normal life accurately during COVID-19 lockdown, when days at home seem eternal? In 2020, July 1 is political again—rousingly, noisily so, blasting through global airwaves as it did back in 1997, the year that day became a public holiday in Hong Kong, when my city returned to China. In case you’ve forgotten, my city was once the site of “a many-splendoured thing,” so titled for the novel by Han Suyin, a Eurasian medical doctor from Shanghai who fell in love with a married British correspondent and carried on a controversial public affair. Her lover died while covering the Korean War. She wrote it as fiction—thinly disguised autobiography—that placed my city on the world’s stage, especially when glamorized as a Hollywood movie. Despite its romantic story, the novel is a critical look at the historical, social, and cultural problems of my Chinese city, this political anomaly, this hybrid, cosmopolitan exclave that flirts with both East and West.

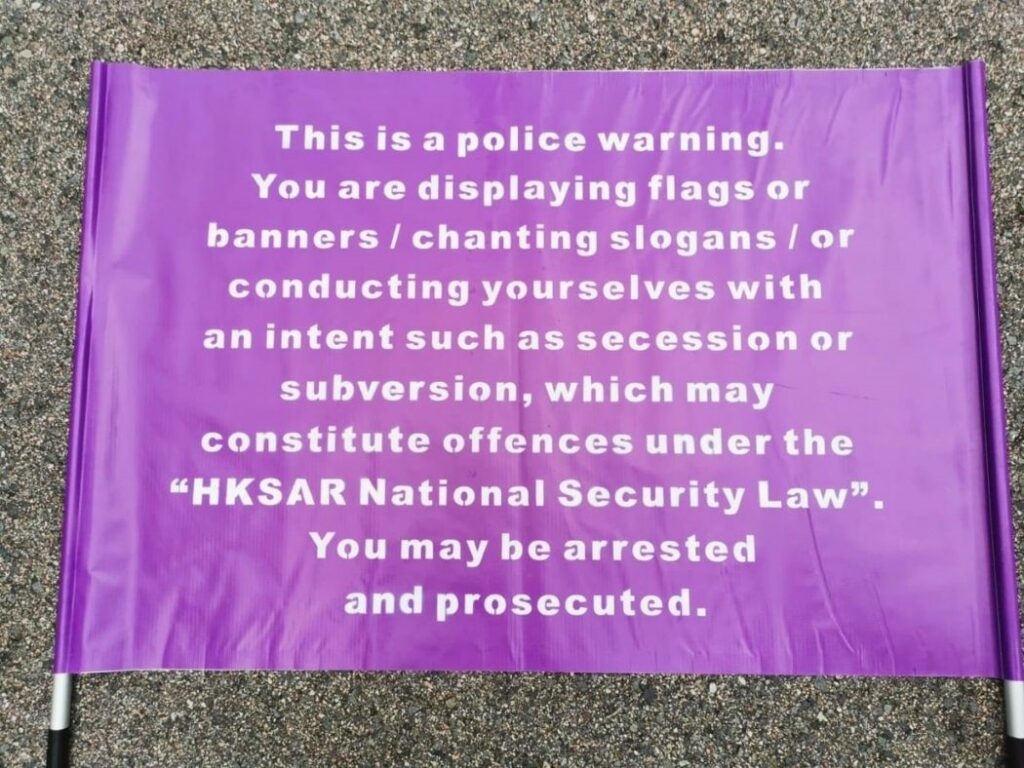

Now, “conducting yourselves with an intent,” as all the purple police banners read that morning in 2020, may lead to arrest and prosecution, an “intent” that’s slippery in meaning—secession or subversion—thanks to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s (HKSAR) NationalSecurity Law that came into effect after midnight of July 1, 2020. Peaceful protests are now threatened, despite our Basic Law, just as the police now have (and continue to gain) increasingly greater powers to arrest people for questionably “illegal” activities. “One country, two systems,” the promise, among others, that Hong Kong’s rule of law will be separate from mainland China’s legal system, is a debt of borrowed postcolonial time to retain our hybrid and cosmopolitan way of life for fifty years, until June 30, 2047, to be exact. That morning, however, our lender extracts a rather large repayment, muddying the contracted time frame. Once again, I am watching my city vanish just a little more. Trust me, this is notfake news.

The flow of bounty that was Hong Kong is closing on my vanishing city, not unlike the outdoor spigot that had to be shut off in my northern New York home, the morning I awoke to a flooded basement, the year COVID raged.

1997 used to be the flash-forward year of my childhood and early adult life. Until the early ’80s, it remained that ninety-nine-year mark, the year the lease on a part of my city’s land mass was due to expire on June 30. How was it possible to rent a piece of a country? I wondered, when this anomalous arrangement of the Convention of 1898 first entered my consciousness, a Sino-British agreement to lease the New Territories and 235 outlying islands to Britain, expanding the colonized city’s territory. I think I was around nine or ten when the true meaning of Boundary Street became clear. My school was located on the north side of the street, which meant I daily crossed the border from the British colony of Hong Kong into the People’s Republic of China, geographically and politically a part of the leased New Territories. How was that possible, my yet-to-be-decolonized mind inquired. Dad’s answer was unequivocal: This is why you do not want to be a colonial “British,” although he never fully clarified why I wasn’t entirely “Chinese” either—since we were Indonesian citizens—even though I walked, talked, and certainly looked Chinese enough, despite my mixed blood. National affiliations are, however, difficult to ignore when I recall my passport. During the global COVID pandemic, my present document is getting a long reprieve, resting between its midnight-blue, made-in-America covers, unable to take me across borders that remain closed, forcing me to be only a virtual citizen in my city.

I never did become British, privileged as my family was to be Indonesian, although I retain my Hong Kong permanent residency. Back when I sported a dark-basil-cover passport, it felt odd rather than privileged, because I looked and sounded nothing like most Indonesians. There were quite a few of us foreign Asians perched in my British colony for many decades before 1997, mostly from Southeast and South Asia, as well as some from Taiwan and Vietnam. The Filipino wave happened later, in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Many of us were ethnically Chinese. Among those who were not, many, myself included, spoke Cantonese like natives, and several generations of these families called the city home. It was true for some British and other non-Asian nationals as well. Even though Cantonese people comprise the majority population, my Hong Kong is a city that has always looked out toward the world, this special administrative region that still is, and will be, for the currently foreseeable future, an exclave of China, one not entirely subject to Chinese national law.

At some point, it became possible to forget about 1997. Even when Wong Kar-wai released 2046, his excruciatingly beautiful and romantic 2004 feature film, it was all about love, obsession, and nostalgia for the way we used to be, as well as the way we perhaps wished we could continue to be. In the film, 2046 is the year of a speculative, dystopian future and also the number of a room that is unavailable for rent because a murder happened there, so the protagonist is offered room 2047 instead. Despite the film’s apolitical drama, it is impossible to ignore the political overtones, an allusion to when our decolonized-recolonized, one-country-two-systems arrangement is contracted to expire. How is it possible, the world wonders, for a country to embrace two systems within its boundaries? If you’re from Hong Kong, the answer has always been blindingly crystal clear. Once an anomaly, always an anomaly. My city is all about walking and quacking in sync with whatever power prevails.

Despite all that, July 1, 1997, remains difficult to forget. The optimists and pessimists erupted side by side on the eve of that day. Even though social media hadn’t yet begun spewing its freefall lava of words and images, the world’s media and intelligentsia pontificated loudly about the past, present, and future of my city during that year, the year China brought us “home.” My city was like a virus, infecting global chatter for a brief moment, banging pots and pans about our fate. Dire, so dire, many experts decreed, although many others, myself included, thought differently. Memory tricks you into thinking the past is like the present, doesn’t it?Yet what we think we know about life is a perpetual present tense in this deluge of knowledge, blurring conflict into a predictably repetitive cycle of I-scream-you-scream, like the song about ice cream, a sweet indulgence that, in the heat of the moment, melts and disappears.

In 1997, I walked through my city on the night of June 30, stopping into local parties, gliding past the Chinese ones, and witnessed Hong Kong’s democracy protesters take their stand one last time under British rule. The protesters were stalwart but few that night, not of great concern to the local police. No one demanded independence or threw petrol bombs. “Foreign interference” was not evident enough for Beijing to squawk. Besides, the police had all those important dignitaries to protect from the rain, as well as crowds to control at our newly extended giant tortoise shell, the Convention Centre, where the handover ceremony took place. It was at once wistful and celebratory, a good night to walk.

Now, I walk through those nights in memory, this city of mine that lends itself to long urban rambles, this city that was so safe and free of crime and disorder, this clean and orderly city where trains were graffiti-free, where universities were spaces for ideas, argument, and debate and no one worried too much about politics or the future, because the future was always willfully rosy. Am I just a deluded flaneur of remembrance, courting nostalgia, because I, too, refuse to accept the inevitable, hoping that the way we have become is the way we will always continue to be, a future as a global Chinese exclave with a separate but equal system and culture, in the twenty-first century and beyond?

. . .