Someone holds the makeshift beach up from one end, and the world floods, swell surging to one side of the homemade wave machine before the water rushes back, quick, aggressive, eroding bits of the science-fair project with violence before softening slowly, slowly. Repetition eventually grinds everything down to nothing.

We are supposed to make a good wave, seventh-grade science a mixture of earth studies and physics, building habitats for the bugs we capture and let wander our palms before we stick a pin through their abdomens and watch them scurry to nowhere. Their bodies flatten slowly, slowly. We learn about the squid that undulate off our California coast, watch them billow and burst in a video before we fry and eat samples our teacher brought in, crunching the creatures to a rubbery pulp between our strong white teeth.

The year is an exercise in power—who controls the land and the bodies on it, how much fear means to the ones who aren’t feeling it, the frequency with which some of us will feel terror crash over us in waves.

Middle-school science class is where we learn the female body is destined for dissection, that womanhood means an inevitable encounter with the slick edge of a blade, boys and men thrilled by their power and our panic, our pregnant mothers—eventually ourselves—ripped open by the surprising strength of our own bodies, or sliced open via episiotomy and cesarean, the ultimate experiment.

I learn like this: The task is to slice through the pale flesh of an earthworm, those delicate creatures that curlicue across the cement when it rains, girls squealing as they try not to grind them underfoot, the boys stomping proudly behind, their sneakers slick with death, threatening to push the girls into that which we do not want.

We have to do this, the teacher explains, scalpel glinting in his hands. For science.

Already science is gendered, math too, the teacher telling us girls that we might not be cut out for algebra or geometry, many of us believing it, for why else would all the examples from the book involve trucks or trains, things we will never command? Our names are never in math problems, which feature Dave or Scott instead.

When the girls protest, squeamish about the killing or the knife, our science teacher decides we need assistance, partnering each girl with a boy who might guide her hand.

My partner is the boy who has spent the year tickling me, watching me gasp for breath, growing powerful despite his much shorter stature because I cannot protest, move, speak at all. Perhaps he’s seen men do this to women, wrap their grip around a woman’s throat, render her speechless with a hand, a cock. Pornography and the newly popular South Park are all the boys talk about in the halls, raising their voices for everyone to hear about how the new ’90s internet is making them men.

I try my best to avoid the boy near the lockers, where he reaches under my backpack toward my ass. I try to avoid him in concert band, where he strokes my clarinet up and down, chuckling at his innuendo, or thrusts his trombone slide toward me, trying to frighten me with the noise before clearing the instrument’s spit valve at my feet, on my back, another poorly mimicked trick he’s picked up from the web.

I try to avoid him in science, where he and the other boys reign supreme despite grades that put them lowest in the class. We sit alphabetically at first, but as the semester wears on, the girls ask the teacher to move until, one by one, we all sit at the back table, our gender in a long row.

His name is Patrick—the name of boys in math books, boys with blond bowl cuts (which he has), boys who like to whisper pussy and tits to see girls blush at their own bodies, boys who think that frightening girls is the same as flirting. And when the time comes for me to hold steady the scalpel in my hand, tower over a creature that has done nothing to deserve dissection, he does what boys named Patrick do. He lifts the back of my shirt, exposes me, and tosses down the worms he’s casually slashed to bits. Then he turns to bow in front of the audience of boys he’s assembled to witness.

I scream. Turn sharply with the scalpel. I feel his wet trickle down my back, hear laughter. A dozen sets of eyes dissect me. A chorus: “You like that?” “Ooh, dirty girl.” “Does that feel good?”

Our teacher sends Patrick outside for the rest of the period, sighing at our hormones and inability to focus. He taps through the glass at me like I’m a bug on display.

The boys continue to stare, but now their smirks stretch thin and angry, a look that will become familiar throughout my life, the look of men angry at women who tell them no. Now I’m not a “dirty girl,” but “dramatic,” “a bitch.” They pout, refuse to talk to me or the other girls in our class, the ones they’ve been forced to work with when we all know who owns knives and hurt and science.

Patrick returns the following day, his and the other boys’ attention renewed. They know that if a woman protests, she must mean yes. Hands at my neck, my lower back, my waist as I bend over beakers. All year they experiment with what they can get away with.

The girls praise the attention I receive—with desire comes power—while simultaneously feeling sorry for me. They know better than to speak up, lest the attention turn to them, their own bodies. Most keep their heads down, hunched in front of their experiments, turning now and then with wonder and worry to watch the circle of boys closing in around me.

I still remember turning abruptly, the scalpel in my hand. My female body knew instinctually to brace for violation, violence. But I did not swing the blade. Instead, I held it close to my body. One slip and I could have harmed myself. This, too, was instinctual—hold yourself still, prepare for harm. Know you are destined to hurt.

When our teacher had ushered Patrick outside, he placed a hand on the boy’s shoulder. When he returned, he snatched the scalpel from my hand. I’d been careless, he said. I could have hurt someone.

Shame on me.

. . .

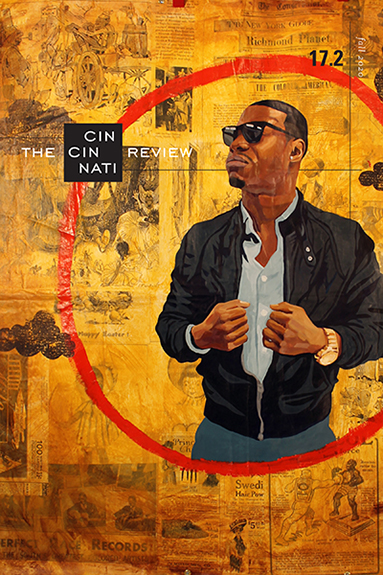

For more of this essay or other great literary nonfiction in issue 17.2, order now in our online store. Digital copies are only $5!