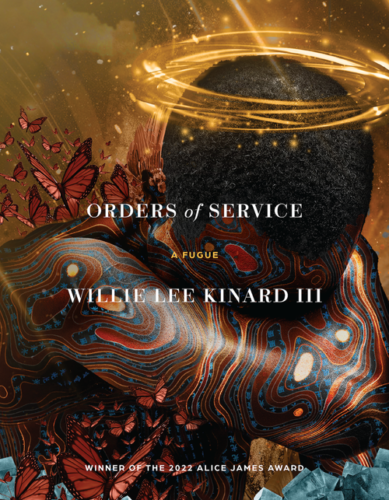

Chimera, Chimera: A Review of Willie Lee Kinard III’s Orders of Service

7 Minutes Read Time

Editor’s note: In a new effort for our site, we plan to publish occasional reviews that go beyond a recitation of a book’s “pros and cons.” (FYI, we are not accepting submissions for this series yet). Here’s our first, by a contributor to both our miCRo series and our review feature in the Issue 18.2 feature on joy, hope, and delight: Daniella Toosie-Watson.

Daniella Toosie-Watson: I grab my laptop and Willie Lee Kinard III’s Orders of Service (Alice James Books, 2023) and sit at my grandmother’s kitchen table. It’s 5:30 a.m. I’ve often turned to poems in times of deep grief, though not necessarily for remedy. I know that poems are not therapy. But I know how to navigate a poem in a way I don’t know how to navigate certain griefs. I don’t experience depersonalization often, so I don’t know how to regulate here in this unfamiliar space where it feels that I have two bodies—one spectating the other.

Instead, I do what I know to do. I stir my Bustelo coffee with too much milk and just enough sugar and open to the first poem of Kinard’s debut poetry collection, winner of the 2022 Alice James Award. Kinard is a poet whose work I’ve long been familiar with, so I’m grateful for the chance to read the full-length book. I read one of the collection’s epigraphs from Solmaz Sharif, “It matters what you call a thing.” I wonder how this question of naming will serve the collection. I wonder what the experience of reading and the bodily act of consuming my coffee will feel like in my dissociative state.

The prelude poem, “Self-Portrait as the Cricket,” opens: “The way my legs sit, slightly curved around the knees, / old women squint their eyes yet still ask me if I’m single.” That second line upturns the first line’s image of a cricket, making the sitting pose about sexuality instead—immediately Kinard refuses my expectations of what the poems will be and become. The poem ends with the interplay of images that transform the body of the speaker and the speaker’s lover:

A boy plucked a chirp from me like I was a grass blade.

My own name is a field of chirping.My own name is a church of fields.

I listen for it when I put a man on his back.A man on his back is a call & response.

My own name is a choir of churches.My own name is a chorus of strumming.

Some nights, the only refrain I care sung.

Each line puts a phrase from the previous line in a different context; swift upturnings and interchanging images like this reoccur throughout the collection and are the spine of Kinard’s complex, stunning, and unexpected image systems. These defining formal decisions are most distinctly signaled syntactically, with the right line breaks at the most precise moments.

The social sphere is vital to poetry. For example, a myth is a story once believed to be true, made a legend through a society’s collective effort toward disbelieving. In Kinard’s poems the moments when the speaker has social interactions—whether with the old woman, or during sex with a lover—ground the otherwise mythological poems in the mundane of everyday life. As the mundane is weaved in, it desensationalizes the mythological and makes it a part of the natural fabric of the book’s world. “To Be Feral” opens in myth: “In the dream where chimeras emerge from the sea, / Daniel fantasizes of water-winged options & I am the beast.” “Chimera,” I say out loud. “Chimera. Chimera.” This is how I find the word, what the poems do. It’s also how I newly frame what my body is doing in this state of depersonalization. With a clear voice that meticulously interplays different textures of sound—meter and consonant, image and line break—the poems transform themselves.

In reading this collection, you, too, are a chimera. In “B{u/i}tter Pecan Apocrypha” the directions ask that you “complete the passage by selecting the fitting pronoun”:

{You/I} already work for the Lord, {you/I}’ll claim that.

{You/I} do not want to be saved. {You/I} want to be born.

{You/I} want to be stomached, eaten in spite. {You/I} want to spite

in one sinner’s unmentionable work.

You, the reader, are implicated here, and then you are not. The “I” is also implicated. And, at times, neither is. There is the version of the poem where “I” is both you and the speaker. Then there is the version where there is only God: “God blew {you/I}nto an icebox & called the tasteful Sweet.” There is the version of the poem “God blew [into] an icebox & called the tasteful sweet.” But take heart, God has not forgotten you. There is a version where God finds you sweet too.

I close my laptop at the last line of the final poem, “Revival,” a poem “after Patricia Smith”: “white sheet descends / unison / ascension.” In the wake of this stunning debut collection, I sink into my body like the sugar collecting at the bottom of my mug, under a white sheet of milk, as if the sugar is bowing at the altar and a deacon sheathes its body to protect it from a wayward worshipper’s gaze.

No, this review does not end with my depersonalization being remedied by the collection. I did, however, come out of the experience of this stunning debut with a new taxonomy for myself—for what doubles my body—as well as the confidence to name myself outside the bounds of singularity, in the ways that the poems are unafraid to name themselves. Consider the opening of “Catalog of My Obsessions or Things I Answer To:”

alphabetization; ancestry & lineage; alternate endings; anonymity; antonyms;

arrangements; Babel; Balm in Gilead; Blackness & beauty; book lists; Book of Daniel;

bumblebees; call & response; calling & messaging; cemeteries & necropolises;

chimeras; choirs & choir culture; choral responses; church; church services; cicadas;

Then, consider the speaker unflinchingly renaming his lover in “Hymn: Throw Honey to the Wind & Watch Bees Come Back,” from Daddy to darling.

Don’t ask me, darling, I would like to think

it does feel better with the hat on,

knowing I will not give you sugar

& won’t call you Daddy; tonight,

that is not your name.

To name a thing is to reach toward stability: stability of identity, of place, and so forth. But the problem of naming is that the borders of identity and of place are ever in flux. However, in this collection, naming does not set a boundary. Naming, instead, is expansive. Think: amoeba, calling into himself the possibilities of who he is and can be.

After reading this collection, we have been gifted a new name: with this silk-spun debut, Willie Lee Kinard III has named a new model of form within and across the literary landscape. I say my own name, and from the sounding emerges the promise of being back in my body.

Daniella Toosie-Watson (she/they) is a poet and visual artist from New York. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, the Paris Review, Callaloo, Virginia Quarterly Review, Poet Lore, The Cincinnati Review and elsewhere. They were a profile writer for The Kennedy Center’s Next 50 and are currently a visiting professor at Pratt Institute. Daniella received their MFA from the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program.