Getting Away with It: Epistolary Fiction

10 Minutes Read Time

Assistant Editor Lily Davenport: While epistolary fiction isn’t a literary sin, exactly—we haven’t collectively reached the point where it’s reviled on the level of, say, second-person narration or writing about writers—it is, for many readers, a bit of an indulgence. Epistolary novels have arguably been on the decline ever since their heyday in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; in our current moment, while there are occasional breakthrough successes such as Julie Schumacher’s Dear Committee Members (2014) or Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone’s This Is How You Lose the Time War (2019), epistolary forms are, for the most part, treated more as curiosities than subjects of serious craft or literary-critical interest. (My most compelling piece of evidence for this is anecdotal, but stark: of the ten book-length secondary sources I compiled in relation to the subject for my PhD exams, only two address epistolary forms directly.) But the epistolary toolkit, which I’m treating here as encompassing forms ranging from the true novel-in-letters to diary entries, found text, and other faux-documentary approaches, is a rich and varied one—it insists on the reader’s interpretive participation, and offers powerful methods for developing character and setting and for playing with the progression of time. So: what, supposedly, is wrong with it?

I’ll lay some of the blame on good old-fashioned misogyny, since the epistolary novel, especially in its most traditional, missive-heavy form, is often associated with women as writers and as narrators. In many of the best-known epistolary works, including early instances such as Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778) and Jane Austen’s Lady Susan (1871), as well as later ones like A. S. Byatt’s Possession (1990) and Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah (2013), women employ epistolary forms to examine their female characters’ inner lives at length, and with a level of intimacy that those same characters, for the most part, can’t access in a conventional scenic framework, given the constraints inherent in their settings. Both Austen and Byatt provide missives from women who have no other opportunity to express their feelings or describe their experiences: Austen’s Frederica requires a communicative channel into which her domineering mother cannot intrude, while Byatt’s Christabel conducts an affair almost entirely by mail to avoid suspicion from both her previous partner and society at large. Since women’s internal lives aren’t of particular interest to many patriarchally acculturated readers, narratives that focus on them often wind up framed as unserious at best and actively threatening at worst—and the method of delivering that focus, the epistolary form, becomes implicated as fluff by extension.

But misogynistic reading norms aren’t solely at fault. Epistolary elements are often accused of gimmickry, and their mechanical utility for exposition doesn’t help with that reputation. Even a conventional letter, conventionally presented, provides ready information about the time and place in which it was composed, as well as identifying details about the sender and recipient—and that’s just in the header and salutation!—so epistolary forms are of particular use to writers working in genres that demand more and faster exposition, including most nonrealist genres (speculative fiction, fantasy, horror) and some thrillers and crime fiction. Carrie (1974) is an epistolary novel; so, by my definition, are Max Brooks’s World War Z (2006), Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (2012), the aforementioned This Is How You Lose the Time War, and Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents (1998). Not coincidentally, these are also genres that tend to be perceived as unliterary or unserious—Carrie’s and Gone Girl’s runaway financial successes and Butler’s formidable reputation notwithstanding. Even Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), a novel that has been rescued from genre-based dismissal as thoroughly as is possible, is hardly ever described or discussed as an epistolary text; critics have largely ignored its formal elements, beyond a basic acknowledgement that the book includes some myths and legends invented for its setting on the alien world of Gethen. Though it’s one of the book’s most frequently quoted chapters, the anthropological memorandum about Gethenian sex and gender is too often treated as a slightly embarrassing exposition dump, when in reality it’s doing a lot of additional work: giving us a benchmark against which to gauge the human narrator’s attitudes about gender, reminding us of his role as curator of the book’s many texts, and supporting the book’s thematic concern with the impossibility of establishing a single, coherent narrative on which all its participants can agree. This kind of work is stealthy and unglamorous, and usually far from obvious on a first reading; it showcases epistolary forms at their multivalent finest.

Then, too, epistolary forms are common in satirical novels such as Dear Committee Members and Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger (2008), as a consequence of their unique capacity for flagging narrators as explicitly and humorously unreliable or un-self-aware. Again, this is a genre that’s often perceived as literarily lightweight, though the solidly canonical Nabokov pulls the same vocal trick, and plays it for humor much of the time, in Pale Fire (1962). Both Schumacher’s and Adiga’s novels consist entirely of a one-sided correspondence, a choice that escalates the already-voice-forward nature of the epistolary form and explicitly invites us to mock the foibles of the narrators and the absurdities of their worlds—albeit not in equal measure, since we have to maintain some sympathetic allegiance to the narrating voice if we’re going to keep reading at all. I suspect that, although readers and critics tend to be enthusiastic about how much fun these books are (just ask my father, who once read me a passage from Dear Committee Members out loud over the phone, gasping with laughter), there’s also a widespread desire to not take them too seriously, since their humor stems from bleak realities about, respectively, the lasting effects of colonialism and the corporate collapse of higher education.

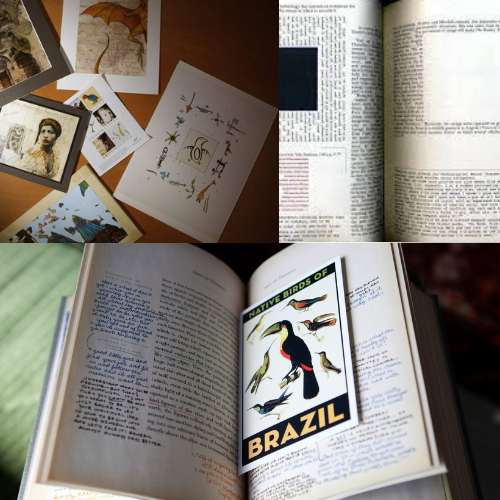

A bizarre inverse of this critical fate, however, has befallen ostentatiously experimental texts such as Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000) and the Doug Dorst/J. J. Abrams collaboration S. (2013). (Nick Bantock’s Griffin and Sabine (1991) arguably belongs to this category as well, as it troubles the line between novel and artist’s book.) As many readers and reviewers have simultaneously praised and bemoaned, these novels make extravagant use of the epistolary by foregrounding it so much that it eclipses the text’s other aspects—the structural conceit outrunning any of the narrators that are supposedly generating it. (No one would describe House of Leaves as ‘a book about a documentary film crew and a very disturbed man,’ although that’s technically what it is.) These are books that use the epistolary to call attention to themselves as objects, paradoxically limiting the reader’s immersion into the story and requiring our active, detective-like attention to it, and sometimes even our physical manipulation of the book, as is the case for S. We’re at once recruited and rejected by these novels, never allowed to forget that we’re reading a text that’s separate from ourselves yet simultaneously forced into a participatory relationship with that text. Because it’s not predicated on our investment in a particular character or in a relationship within the story, this kind of reading experience can ultimately feel empty or self-congratulatory, as if the whole point of the novel were for us to feel powerful and smart (and witness how smart and powerful the writer presumably is, to get us to feel that way). But here, too, the form is connected to the story, characters, and thematic undergirding, although they’ve receded under its shadow: in S., the stories told in the base text and in the annotative correspondence surrounding it gradually and satisfyingly converge on the same set of events, and turn out to follow parallel romantic and scholarly relationships. Similarly, the multilayered annotations at once establish the correspondence-narrative’s timeline and foreground the book’s interest in the challenges of reading the past to better understand the present. It’s the same patient, complex work that Le Guin performs in Left Hand, but hyper-emphasized, lit in neon.

Epistolary fiction is replete with contradictions. It’s bold and voice-centric, foregrounding the narrator’s own perception of their experiences; it’s indirect and sly, speaking volumes about the overall setting, cast, and thematic or philosophical project through its relationship to the text as a whole. It’s bluntly expository—what other form could stand up to a textbook-like, matter-of-fact description of an alien species’ reproductive infrastructure?—and maddeningly obscure, pushing us to get directly involved if we are to have any hope of understanding what’s happening on the page. It’s fiercely authoritative, demanding that we accept the testimony of its speakers (Parable of the Talents); it declares, over and over again, that narrative authority should not be trusted, by providing us with voices that cannot be reconciled with one another (. . . also Parable of the Talents). It’s this last characteristic that, I think, lies at the root of epistolary fiction’s cultural dismissal: its simultaneous claim to and critique of narrative authority is ambiguous and unsettling, and, more importantly, it renders epistolary fiction especially attractive to many writers who aren’t automatically granted such power in a literary or a social context. That means writers who belong to marginalized communities—particularly women, particularly white women, which is a topic for another day—that means writers who work in genres with less literary clout, such as speculative fiction, thrillers, or humor. (It’s not lost on me that all of the examples I’ve provided of ‘experimental’ epistolary work are by white men, and that the books themselves have made their reputations largely based on their looks, which in turn implies a significant budget underlaying their production, one not afforded to the other books I’ve discussed: readers oohed and ahhed over S.’s code wheel and letter-inserts, House of Leaves’s intricate, multicolored type, and Griffin and Sabine’s paintings and glossy ‘handwritten’ letters.) The tools epistolary fiction has to offer may not be easy or fashionable, but I’m grateful as a reader and as a writer for their curious, complicated claim and challenge to authority. I think we’re overdue for an epistolary resurgence—and, if anyone reading this has an epistolary short story that’s burning a hole in your hard drive, I’d love to see it in the queue come December!