Elliston Poet-in-Residence Spotlight: Brian Teare

5 Minutes Read Time

Associate Editor Connor Yeck: This week at the University of Cincinnati we’re thrilled to welcome Brian Teare as the 2023 Elliston Poet-in-Residence. With a public reading as well as the spectacularly titled lecture “It’s the End of the World & We Know It” on the schedule, I’m reminded I had the chance to briefly discuss Teare’s work in a blog post on writing and walking this time last year, and it feels fitting to revisit some of his most striking poetic gestures.

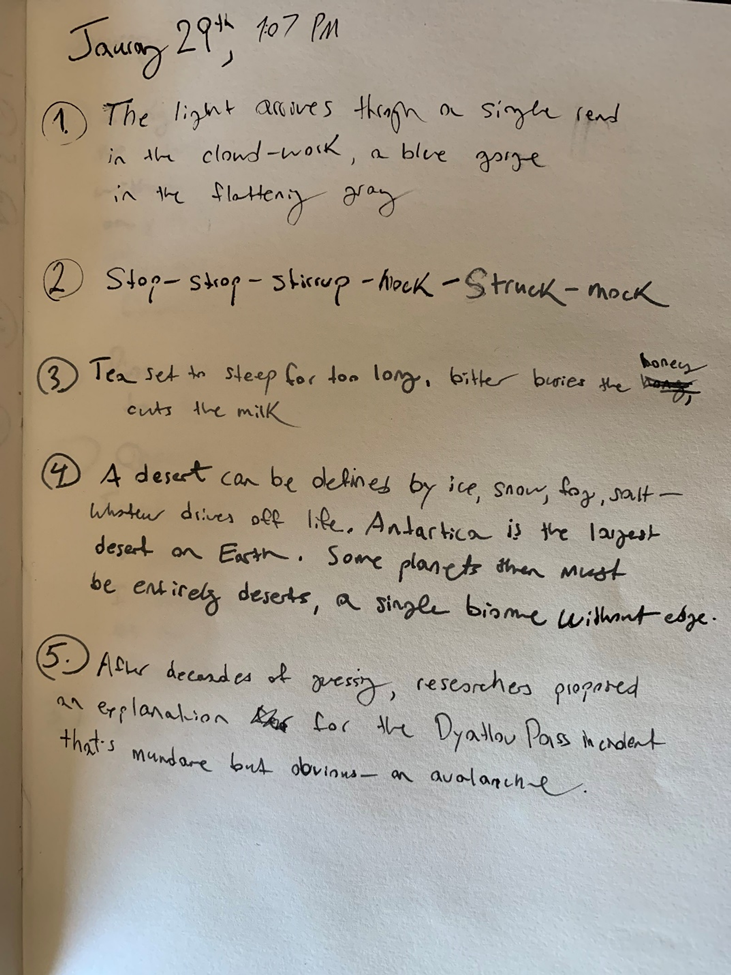

In the spring of 2021, I had the chance to take an especially generative poetry workshop with Professor Aditi Machado. Looking back at the experience now, my two fondest memories were reading Teare’s 2019 collection Doomstead Days, and doing a prolonged note-taking exercise. Over a two-week period, we were asked to practice “relentless but paced attention” by responding to specific language-driven prompts: observe the quality of the light in your writing space; devise a group of words bonded by their sonic rather semantic qualities (e.g., pestle—pistol—primness—kestrel—privy); interact with something nonhuman by tasting or touching; quote a line from something you’re currently reading; note something happening in the world that day, be it global or personal. We were further asked to write in unfamiliar spaces and to invert our creative comforts. If we usually write in silence, write with music; if we write at our desk, write instead at the kitchen table or outdoors. Perhaps most importantly, we were asked to never edit ourselves but to ceaselessly transcribe whatever emerged from our internal and external environments.

Thinking of Teare’s poetry two years onward, I’d assumed this note-taking exercise was directly paired with our reading of Doomstead Days, but after a lengthy excavation of emails, I found the two were separate occurrences in a semester brimming with prompts and exercises. What made me assume so easily they were linked in a larger lesson? It ultimately comes down to the sort of observation-driven alchemy Teare’s poetry achieves through its own “relentless but paced attention.” In Doomstead Days as well as the visceral craft essay “En Plein Air Poetics,” Teare takes on the monumental task of experiencing, translating, and cataloging the Anthropocene. Above all, we as readers are asked to consider a commitment to “poetry as fieldwork”—not simply turning to our surroundings as poetic observers but to realize our role as active, biological participants in a vast array of natural and humanmade systems.

For example, in “En Plein Air” we’re treated to an exhaustive, meditative account framed by a daylong hike near the Lehigh Gap Nature Center in mountainous eastern Pennsylvania—a one-time Superfund site slowly reclaimed through natural regrowth and human stewardship. Traversing field, forest, and rocky outcrop in an upward trek, Teare luxuriates in ecological, geological, and atmospheric specificity, and the act of intimate documentation. With every passing mile, “details come into focus with an oxygenated crispness”— “fungi . . . [in] colorful rows of rot,” and “small ferns . . . miraculously green past December.” We gauge the weather, the light, shifts in temperature, as well as our crossing into different ecotones (transitional spaces between biological communities). However, this isn’t a pristine, humanless landscape—in fact, far from it. Birdsong and wind heard through barren branches seamlessly jostle with “the occasional gunshot [echoing] across the state game lands” and “the dull hum of the highway,” intrusions assigned the same amount of experiential weight as their natural counterparts.

For Teare, “writing while walking makes explicit the intimate relationship between a site and my body,” an unmooring process through which the “mind goes from translucent to luminous, its usual wash of thought polished to a transparency that lets in the world with a force I adore.” I particularly love this gesture because it feels so invitational, no matter how many times I return to it. The ultimate goal of any environmentally centered poetics can seem daunting, even impossible. How do we write on climate change, ecological degradation, and pollution—the vast, weblike array of often-invisible forces that philosopher Timothy Morton describes as “hyperobjects“? Teare offers us one solution that is readily available and malleable to our everyday circumstances, opportunities, and passions. Be it a hike into the deepest wilderness, going down the block, or the walk through Burnet Woods I’ll take to UC’s campus to attend Teare’s reading, we can always anchor ourselves deeply within “the intertwining of ecosystems and anthropogenic change.” Poetry once more becomes a vehicle of intensely localized experience, and a chance to freshly view the immediate terrain that’s perhaps become blurred in our daily rush. It’s a commitment to locate ourselves in the larger biosphere. Among flora, fauna, weather, geologic formations, and human-driven phenomena, Teare asks us: Where do our bodies exist, what do they tell us, and how can a poem transmute this unfiltered data into something even greater?