microreview & interview: Taneum Bambrick’s Vantage

7 Minutes Read Time

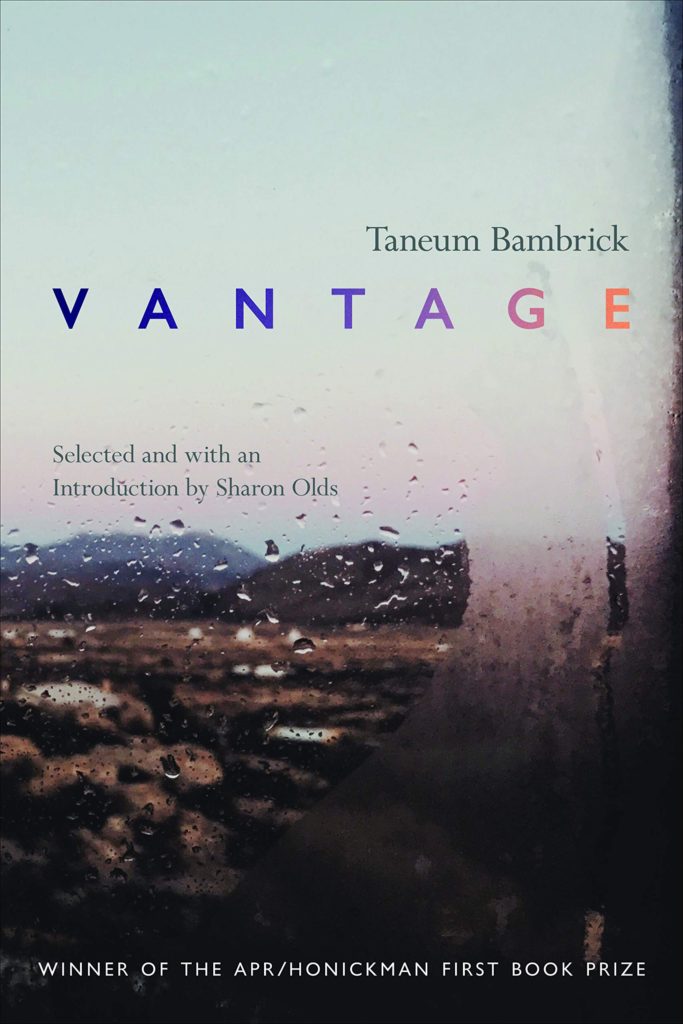

Editorial Assistant Nicholas Molbert: I was first drawn to Taneum Bambrick’s full-length debut Vantage (Copper Canyon, 2019) because it had “an ecological eye,” but after reading the collection, I realize how much of a disservice it is to characterize this book solely as environmentally urgent. On the surface the story is simple. We are led through this unsectioned, relentless collection of (in Sharon Olds’s words) prose poems, lyrics, essay-poems, and stretched lyrics with off-rhymes, off-rhythms, off-images, and off-grammar by a speaker who is the only woman among an otherwise all-male garbage crew tasked with caring for the grounds of a dammed town. Through this backdrop, Bambrick explores and interrogates the griefs and violences occurring at intersections of class, gender, and forgotten rural places with piercing clarity and music.

I got a chance to talk to Bambrick, now a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, about how permission, power, intimacy, and memory figure into the formation of her APR/Honickman First Book Prize–winning collection.

In an interview with Aileen Keown Vaux for The Rumpus, you explain the writing exercise that led to the first poem in Vantage, “Litter.” Bruce Beasley, your undergraduate professor, tasked everyone with writing three “sense” words on slips of paper, dropping them into a bowl, drawing three slips, and writing a poem based on what you drew. You described the writing of “Litter” using the words (“blue,” “garbage,” “condom”) as a process of giving yourself permission to write the concrete details of your own life. How else does permission play into the collection?

Permission—from myself and from other people—played a very important role in writing this book. The poems and prose pieces in this collection are a kind of autofiction. As a survivor I always worry about my ability to remember things accurately because of the effects of trauma on declarative memory. Through writing this project, I came to the realization that what happened to me belongs to me, and the way that I hold onto my past emotionally is a kind of truth even if it isn’t a literal one.

While writing I always struggle with my own obsession with honesty. That obsession is linked with other determinations, like recovery. I had to give myself permission to create a world in this book that valued its specific social and environmental urgencies over, for example, the order in which events unfolded. In publishing the collection I also gave myself permission to enter a space of less safety. For example, I’ve found it dangerous to admit, in writing, that a person hurt me. Even though none of the people in this collection are exactly the person who they represent—the names are changed, moments are conflated—people have seen themselves in those characters. Even people who I wasn’t writing about.

Permission, like apology, can often put people in the position to answer to something they don’t want to revisit. There are always power structures at work, too, that can force people to say the opposite of what they mean. For that reason, we can’t think of these conversations (even with ourselves) as a one-time exchange. When I write, I am always committing to the pursuit of a particular morality. It doesn’t matter to me, for example, how someone who abused their power might feel if they see that abuse represented in one of my poems. It does matter to me how my father feels when he reads about our arguments, or how the friends I have from the garbage crew react to the way specific incidents are represented.

Are there things you tried to write about but only did so unsuccessfully until they found a place in the collection?

Yes, I think there was a kind of “shadow” to this project that mostly surfaces toward the end of Vantage. When I initially wrote this book as my thesis for my MFA, I wrote it with an entire second section that didn’t make it into the final draft. That second section ended up condensing into the lyric essay, “Sturgeon,” which falls toward the end of the book. In that essay, I found the space to articulate some of the concerns that act as a backdrop to the collection: assault, homophobia, family dynamics. Because of my relationship to each of those subjects, I struggled to represent them in the space of a poem.

Writing “Sturgeon” was a way of revising, processing, and braiding the material that was the most important to me. I was very worried about hurting people when I started writing this project. I was worried that the man who assaulted me would find me, on the internet, writing about him. Having a strong community helped me worry less about this, but I do think concerns of safety played a huge part in how I drafted this collection.

For me, “Sturgeon” highlighted an already formally virtuosic collection. How did the form of “Sturgeon” help you process your relationship to those backgrounded concerns as opposed to negotiating the concerns in poems in earlier manuscript drafts?

Writing “Sturgeon” was my attempt to speak plainly about fear. I knew it was important to me to unpack the complicatedness of specific environmental issues, especially those facing the landlocked white sturgeon of the Columbia River. What I didn’t realize until I brought parts of this essay to a workshop was that it was also important to me to openly address parts of my past and the social concerns those parts represented. I wanted to encapsulate the feeling of realizing that there are problems in life that will never resolve: for the environment, within relationships. Like, when an event disrupts the structure of a family and everyone remembers their role in that event differently. Or, how our literal survival depends on and grows off of systems that trap wildlife.

Of course, it’s important not to conflate environmental and human issues, but I think it can also be important to state when those issues connect. This essay started when my dad told me about a job he had where he carried stranded sturgeon (often ten feet long) out of a dam on a human stretcher. Watching him patch together wildlife habitats is my representation of what hope can look like in a contemporary society fixated on denying its most difficult truths. I have always been invested in the questions of when and how a subject becomes incommunicable between people, and this essay stems from that fear of language. Of the ways in which we risk losing each other and natural spaces.

Taneum Bambrick is the author of Vantage (Copper Canyon Press), which was selected by Sharon Olds for the 2019 American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize. Her chapbook, Reservoir, was selected by Ocean Vuong for the 2017 Yemassee Chapbook Prize. She is the winner of an Academy of American Poets University Prize, an Environmental Writing Fellowship from the Vermont Studio Arts Center, and the 2018 Booth Nonfiction Contest. Her poems and essays appear or are forthcoming in the New Yorker, American Poetry Review, PEN America, Narrative, and elsewhere. She is a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

Nicholas Molbert lives and writes in Southern Ohio and is a PhD candidate at the University of Cincinnati. His chapbook, Goodness Gracious, is forthcoming from Foundlings Press in December 2019, and his work is published in or are is forthcoming from The Adroit Journal, American Literary Review, The Cincinnati Review, Missouri Review, Ninth Letter, Pleiades Book Review, and Permafrost, among others.