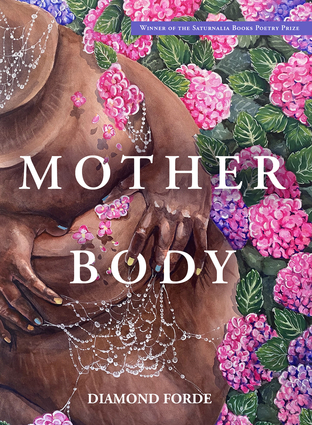

Editorial Assistant Marianne Chan: I became familiar with Diamond Forde’s work while taking a workshop with her at Florida State University in 2019. Forde was in her first year of her PhD program at FSU, and I was an employee at the university and taking the workshop on the side. I remember being stunned by not only the lushness of the images and language in her poems but also the sophistication with which she explores the body, sexuality, self-love, and self-loathing. Because I had a preview of Forde’s work, I was thrilled about the release of Mother Body, her debut collection of poems published by Saturnalia Press in 2021.

In these poems, we watch the speaker grapple with her own love for herself, as she is surrounded by not only racism, racial violence, and fetishization but also oppressive body standards that are reinforced by her family and others. However, as we progress through this collection, the speaker discovers the beauty in her body, celebrating her stomach, her sex, her breath, and, in turn, her life. These poems—with brilliant images and startling musicality—resist erasure and destruction, and they contain a kind of radical joy that I believe is much needed, now more than ever.

I was so happy to be able to talk to Forde about Mother Body.

The first poem and the last section of Mother Body focus on a character called “fat girl” (her name is in lowercase). We watch fat girl taking part in various activities—from reading about Greek mythology to dancing at a block party. When did you begin writing poems using this persona or character? Did fat girl change the way you wrote about the body?

fat girl was always waiting on the edge of other poems, although the first poem she came to fruition in was “Still Life with fat girl, Post-Coitus.” But fat girl started before that, in 2016 after the publication of “Fat Fuck” in The Offing. I was thinking new thoughts about gaze, about the perception of physical excess, and out of those thoughts came fat girl. She gave me space to contend with my racialized and gendered body, to explore the dissonance between “who I be” and “who you see.” I started thinking about the difference between the externalized and internalized gaze. I also realized I needed to be more mindful about the narratives I rely on to convey my body.

Mother Body begins with a beautiful poem called “Blood Ode.” In the notes section, you write that this poem mourns the deaths of “Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and the numerous, numerous Black lives lost to police brutality.” While this collection seems to celebrate the body in various ways, this poem grieves “the blood that won’t return,” and fat girl acknowledges her physical vulnerability: “how many layers would it take to make a bulletproof lung?” Can you talk about the choice of positioning this poem as a kind of prologue to the rest of the collection?

One of the themes contingent to the book is self-love as resistance (important because I’ve been lambasted with narratives that tell me I’m unlovable). But there are two types of self within the book, the embodied self (“I”) and the collective self. The collective self is the community from which I understand myself, and as the book complicates the concept of “mothering,” part of that complexity is thinking about how I “mother” a collective and embodied self. I wanted to understand why a wound against my collective feels so personal.

So, the short of it is this: I love Black folx. I’m tired of watching us die. We deserve better. “Blood Ode” is a part of a book meant to say that.

Speaking of odes, you and I met at Florida State University, in an awesome class that focused on the ode taught by Barbara Hamby. Mother Body contains five odes. What do you love most about the ode form?

That was an awesome class, and I just want it on the record that you wrote some incredible poems there.

To answer your question, I enjoy framing self-love as resistance, and I’m the same way about joy.

Mother Body is a love poem to myself. I was writing this book through a time that felt very joyless for me. I wrote the poems I needed to hear. For a while I started thinking about the book as a sort of friendship. I could tell Mother Body about my mommy issues, and she’d just ask for more. I didn’t realize Mother Body was a book for anyone else until it was contracted. And by then, it became all I cared about.

The odes in this book are about seeing the supposedly deviant thing and saying, “yeah—I see you; you’re valued.” I wrote that because that’s what I wanted to hear, and I thought other folx might need to hear the same.

Mother Body celebrates all aspects of the female body. You’ve written poems about the speaker’s arm hair, stomach, and vagina. In the final poem, “fat girl Climaxes While Working Out at the Gym,” the speaker says: “I want / my pussy to know I have loved it since the first time / I pried its smile into a lazy camera’s eye, / spied its abundance of pink—the trembling lip / of a conch shell or tulip’s dazed and hazy hue—/ and pussy, you are the only me I’ve loved regardless.” In a world in which women are often made to feel ashamed by the appearance of their vaginas, I was stunned by this beautiful description and unabashed praise of the speaker’s “pussy.” Why was it important for you to write about the body in this way? How do you see the speaker’s relationship to her body changing as we progress through the collection?

I joke with my partner that “fat girl Climaxes” is in the back of the book because it’s the poem I least want my mother to see. Really, it just felt like the best poem to end on. It’s an intimate poem, not because of its subject, but in who it chooses to address: a conversation between the speaker and, well, herself—or at least a part of herself that she chooses to love bombastically. “fat girl Climaxes” was part of my desire to say I’m here; I’m going nowhere. And honestly, vaginas are a marvel.

What are you working on now?

Right now, I’m shaping a poetics of excess in a new project that uses the King James Bible as a framing device. In “not-dissertation” language, I’m writing poems about my grandmother. She died in 2007, but I’ve been caught up thinking about how enslavement has changed Black maternity and our relationship to the American South, so I think my grandma still has some wisdom to teach me. You can check out some of the poems in a forthcoming issue of Obsidian or on my website, diamondforde.com.

Diamond Forde‘s debut collection, Mother Body, is the winner of the 2019 Saturnalia Poetry Prize. Diamond has received numerous awards and prizes, including the Pink Poetry Prize, the Furious Flower Poetry Prize, CLA’s Margaret Walker Memorial Prize, and third place in Frontier Poetry’s New Poets Award. A Callaloo and Tin House fellow, Diamond has had poetry appear in Boston Review, Honey Literary, Obsidian, Massachusetts Review and more.

Marianne Chan is the author of All Heathens (Sarabande, 2020), which was the winner of the 2021 GLCA New Writers Award in Poetry. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in New England Review, Kenyon Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Cincinnati.