“What Makes a Life?” Contributors Michael Dhyne and Dean Rader Discuss the work of Cy Twombly, Fathers, and Loss

15 Minutes Read Time

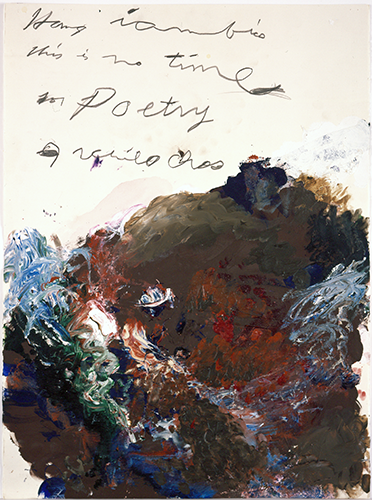

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: As we put together our spring issue, 20.1, we noticed that two poets had written poems responding to work by the painter Cy Twombly, Dean Rader’s “This Is No Time for Poetry,” and Michael Dhyne’s “Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), Cy Twombly, 1994.” We asked Rader and Dhyne if they were interested in discussing Twombly and their poems in a dual interview. Thanks to their efforts, we present that conversation now!

Dean Rader: Michael, I love your poem in response to Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor), which just happens to be one of my favorite paintings (by Twombly or anyone else). While your poem does not really describe the painting or even consider it as a thing to be decoded, it does move back and forth, at least metaphorically, between the painting and the speaker’s memory—which a line toward the end of the poem would suggest is yours. I wonder if you could walk us through how Twombly’s painting maps on to this memory? Or vice versa?

Michael Dhyne: Thank you for getting the conversation started, Dean, and thank you for your kind words! I first encountered Twombly’s work by chance on a cross-country road trip with the dear friend this poem addresses. We were passing through Houston and found ourselves walking through the park that houses the Menil Collection. This friend’s father had recently been diagnosed with cancer; my father had died early in my childhood, and so something in the shapelessness and messiness and brightness of the work felt in tune with our shared grief. When we got to the last room of the Cy Twombly Gallery and were met with the immensity of this particular painting, I felt like my most interior experiences were thrown onto the wall in front of me.

You’re right to say my poem doesn’t really attempt to describe or decode the painting. I think it’s more interested in describing the feelings and revelations the painting elicits. I love that you used the word “map” in connecting memory and painting, as much of the poem is about navigating distances—the distance from one side of the country to the other, the distance between language and what it signifies, the distance between event and memory, the distance between here and gone. The painting itself has a certain narrative movement, which can be read starting at either end. But from left to right, how I first experienced it, we see the canvas moving from the absence of color to the explosion of it, from emptiness to fullness, from silence to language.

While my poem begins with this initial encounter, and a kind of lyric engagement with the painting’s themes and allusions (from Catullus to Rilke), the central memory is the phone call that arrives halfway through, where the friend is grieving the imminent loss of his father. The poem leaves behind the painting completely to tend to the friend in a moment of crisis. Although this conversation ultimately moves the speaker inward, to reflect on his (my) experiences losing a father, the question the poem ends on—of how to find a loved one after they’re gone—is, to me, a kind of invitation back into the painting, back into the world. In this sense, the poem is about a transformative encounter with a work of art, and an attempt at sharing that experience with those that need it most.

I’d be remiss not to mention that this painting graces the cover of your luminous new book, Before the Borderless: Dialogues with the Art of Cy Twombly, which I’ve been savoring the past few weeks. Reading this poem, alongside the rest of your collection, I’m struck by the many parallels between our poems, and the impulses behind our engagement with Twombly’s art. Having never met or spoken, that we’re both writing about Twombly and grief and fathers, and somehow ended up in the same journal, feels amazing to me. I particularly admire the ways in which your poem invites grief in (“give me grief’s profusion, / give me heaven’s crevice call— / let me gaze into what I shall not see, / let the questions, / small as seeds, / drop into the dark garden of the mind”). As with many of the poems in your book, there’s tension here between language and silence, between listening and understanding. We see it in the title, too, “This Is No Time for Poetry,” which is written prominently on the painting your poem is after. Could you speak to these tensions, and share a little about what listening in your poem, and if you like, your book as a whole, means to you?

Dean: Thank you so much, Michael. I appreciate your kind words. The overlap of Twombly and our fathers passing is remarkable. And tragic. I’m so sorry you had to go through that.

In my case, my father’s death was the genesis for my book. He died right around Christmas in 2017, but a few months later, my sister and I met in Oklahoma (where we are from) to go through his things. He had been a very public figure in small town Western Oklahoma—the winner of a hog calling competition, the mayor, the emcee of the Homecoming parade, the announcer at football games, a state championship baseball coach, president of Kiwanis Club—and so had just boxes and boxes of plaques, awards, ribbons, pens, newspaper clippings, and photographs. As we were working our way through his effects, I kept asking two questions: How does one contribute? And What makes a life?

A month or so later, I was in New York and went to a retrospective of Twombly’s drawings over his entire career. It was astonishing. As I was looking at his work, I was doing so through the lens of my father and his life and asking the same questions: How does one contribute? and What makes a life? That night I went back to my hotel and started working on a poem that would become the first in the collection. I had no idea that one event would lead to a five-year long obsession and a new book, but it did.

The poem you mention, “This Is No Time for Poetry,” takes its title from a fragment by Archilochos (“Hang iambics. This is no time for poetry”), which Twombly includes, prominently, in his painting. My poem uses the title as the first line and wonders, well, if this is no time for poetry, then what is it time for? The poem then goes on to ask some big questions and then, as you keenly notice, tries really hard to listen for answers.

For me, the whole book is about seeing and listening. I think of Twombly’s paintings and drawings as having a voice. I think of him as a visual poet. I spent the pandemic trying to hear what he is telling me.

In both our poems, we seem to be entering a painting as a means of trying to make sense of loss. You write above that your poem “is about a transformative encounter with a work of art.” I’d love to hear you talk more about that. How is encountering art transformative? How does engaging with a painting and then making a poem heal?

Michael: These are such incredible questions, Dean, thank you!

To the first, I believe encountering a work of art, and giving it our full attention, can give us another perspective from which to see ourselves or the world more clearly. To be transformed by a work of art might mean something in it inspires action or change, or provides companionship or solace. Personally, I love art where you can feel the artist’s presence. It moves me that I can feel Twombly’s brushstrokes, his scribbles, and the globs of bright paint dripping down the canvas. That I can feel his hands working something out. Or his voice, as you say, trying to tell me something. It’s hard to explain really, but when I’m in the presence of such art, I’m a different person than I ordinarily am, more attuned to myself and others (living and dead), and somehow less rooted in time and space, freer, more imaginative and open to wonder.

The question of how making a poem can heal means everything to me. Discovering poetry in my early twenties quite honestly saved my life. My teacher Greg Orr, whose poems were also born in the wake of early childhood loss, writes about his realization that poems had the ability to not just describe reality, but transform it. This is what drew me to poetry in the first place—to make something meaningful of my father’s death, however small, would be lifesaving to me. Poetry allowed me to write my way out of silence and solitude, and finally begin processing the grief I’d quietly struggled with for so long. It opened me up to the world and made space for healing to occur.

I’d actually love to hear you speak to these questions as well. Your book ends with a kind of prayer for healing, but the yearning to understand or make sense of loss is present throughout. I wonder what your dialogues with Twombly taught you about grief and art making? I wonder, too, what those guiding questions—How does one contribute? What makes a life?— mean to you now, five years after that first poem arrived?

Dean: Your penultimate paragraph is so beautiful, so poignant. I want my workshop students to read it every time they start to feel entitled about making poems.

No one will know this, but I’ve been reflecting on your final questions for a few days now. They touch a nerve, and I’m not sure how to respond. I was actually thinking of my mom, who died last year from COVID. She was a therapist and did pioneering art therapy work, particularly among children from lower income groups. I am reminded often how she (and the practice of art) healed. In some ways, her work is the ideal model of contribution within an aesthetic framework. For her art was literally curative.

In addition to all the things my father did, he was also a celebrated basketball referee. In fact, the first time a high-school basketball game was televised in Oklahoma, my dad was the lead ref. Anyway, at his funeral, a woman I had never seen before came up to me and told me that about twenty years ago, she was trying to break into the world of basketball officiating. But it was nearly impossible for her. She ran into roadblock after roadblock after roadblock. No one in Oklahoma was willing to take a chance on a female referee. Except Gary Rader. She said the only person who went to bat for her was my dad, and that him advocating for her opened doors and changed her life. She told me she drove across the state to honor him. Of all the things said about my dad that day, I remember that interaction the most.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that we cannot predict or map or quantify how we contribute. We cannot know who we touch or how or in what way. Sometimes, I think poetry contributes in similar ways. Maybe poems are a bit like referees in the basketball game of life—just sort of there, ignored by the fans until they stop the game and make us pay attention. Or, maybe poetry is a bit like my dad helping behind the scenes, building bridges. Or, maybe the poem is like the woman driving across the state and talking to me—a kind of dialogue between two people who share little.

I wonder if you could walk us through a line or stanza or passage from your poem that was particularly difficult or unwieldy. What was the breakthrough? How did it happen? How did you make the life of your poem live? How did you resolve that often fraught dialogue between poet and poem?

Michael: Thanks, Dean. It’s so moving to hear about your parents and how they touched people’s lives. It feels true, too, when you say that most of the time we don’t know how we’ve made our mark on others. And yet our imprint is everywhere, seen or unseen.

The line I thought of after reading your question is a line toward the very end of the poem: “I am coming to understand this is about me, as I’ve always hoped it wouldn’t be.“ I rarely remember the conditions under which a poem arrives, but what I can say is that this poem is particularly long by my standards, and that most of it came out in a torrent. It felt like I was desperately fumbling forward, looking in so many places but unsure of the destination.

I was, at the time, assembling the manuscript that has now become my first book, Afterlife (out this fall!), and this poem, the penultimate poem in the collection, felt like it was attempting to tie together so many of its themes—grief, love, absence, intimacy, art, poetry itself. But something I came to realize, after reading through the manuscript, was that the book, which I’d told myself and others for years was about my father, was so much more about me and how I was shaped by his loss. These elegies I’d been writing about him were actually self-portraits.

I think the confession, “I always hoped it wouldn’t be,” is expressing some anguish at the realization that my father’s presence in my poems is a ghostly one. It feels true to my experiences with grief, but admitting that I didn’t feel capable of painting a more detailed portrait of him was a painful place to arrive. On the other side of that, though, was empowerment, the acknowledgement that yes, I am writing about myself, and that’s a valid response to what I’d been through.

I’d be curious to hear about some of the non-Twombly influences on Before the Borderless. Were there any other artists or poets you turned to for inspiration, that helped you keep going or kept you company as you were writing these poems?

I’m so glad you asked this question because I think of the book as a series of conversations. Certainly with Twombly but also with several poets and other artists I was reading (and thinking about) at the time. Without question, Rilke is all over this book—both textually and emotionally. Twombly was obsessed with Rilke, and I am as well. “Archaic Torso of Apollo” is one of the great ekphrastic poems ever written, and his Sonnets to Orpheus and Duino Elegies are the soundtrack to this book. I wish, somehow, he could read it. Maybe he can. Maybe he has. Maybe he hates it!

As I was working on the book, I was reading many different forms of ekphrastic poetry and art writing by folks like Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Robin Coste Lewis, Cole Swensen, Agnes Martin, Anne Carson, and my good friend Victoria Chang.

I was also thinking a lot about Emily Dickinson. The poems traffic in dashes, odd syntax, unusual rhythms. Fragments. Indeterminacies. Death tracks the poems like a dog. I feel her presence in many of the lines. And silences. Also poets like Sappho (I was curious about who gets remembered and who gets forgotten); Wallace Stevens (the limits of language; the ineffability of emotion); Keats (beauty, transience); Jorie Graham (one of the best at blending ekphrasis and philosophy); and, though it may not be obvious, César Vallejo, whose interest in both political and experimental poetics frame this project.

And, now, after this really compelling conversation, whenever I see a Twombly, I’ll think about your excellent poem. And you.

Michael Dhyne is the author of Afterlife, winner of the 2023 Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry. His poems have appeared in Denver Quarterly, Gulf Coast, Iowa Review, and elsewhere. His work has been supported by the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Community of Writers, and the University of Virginia’s MFA program. He lives in Oakland and is pursuing his master’s in social welfare at the University of California, Berkeley.

Dean Rader has authored or coedited twelve books, including the poetry collection Self-Portrait as Wikipedia Entry and Works & Days, which won the T. S. Eliot Prize. Before the Borderless: Dialogues with the Art of Cy Twombly, appeared in 2023 from Copper Canyon. He is a professor at the University of San Francisco and a 2019 Guggenheim Fellow in Poetry.