Interview with Rebecca Lindenberg

26 Minutes Read Time

26 minutes read time

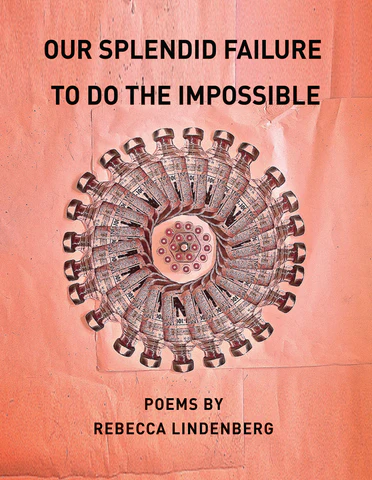

Assistant Editor Andy Sia: Poetry Editor Rebecca Lindenberg’s new book, Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible, is out now at BOA Editions. I was moved by the book’s exploration of time, which spans from the nature of ruins to apocalypse and future times to, intimately, what it is to live with type 1 diabetes. I have long admired Rebecca’s work—I feel lucky to be her student—and I am glad to have the opportunity to ask her a few questions about her new book and her process.

Rebecca will read from her book at the Elliston Poetry Room at the University of Cincinnati on Tuesday, October 29, 5:30 pm EST, in a celebratory reading highlighting new books by UC English Department poets. Additionally, Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman will read from Mom in Space, and Curator of the George Elliston Poetry Room Michael C. Peterson will read from Tom Postell: On the Life and Work of an American Master. This event is open to all.

Hi Rebecca! Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. I am always curious about the process in which a book comes together. I wonder if you might touch on the challenges and joys of writing Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible.

Hi, Andy! First, thank you so much for taking time with my work and for giving me the opportunity to share my thoughts about it with such a wonderful interlocutor. I really value this exchange with you so much.

I think the two most significant challenges I experienced working on these poems were, on one hand, a series of emotional or psychological challenges and on the other hand (but at the same time) a series of poetic or artistic challenges. The emotional challenge arose from trying to write about my experience living for thirty-five-plus years with type 1 diabetes, which I think is probably the thing that hurt me into utterance as a writer in the first place—though I’ve mostly dodged writing about it explicitly until relatively recently. Not all of the poems in the book directly address this particular subject matter, but I hope enough of them do and in varied enough ways to provide the relentlessness and inescapability of chronic disease as a context for the other poems in the book. Chronic disease generally, and mine perhaps in particular, can be really scary—so turning over and over the language I’ve consciously and unconsciously internalized and also revised for myself regarding my condition was also sometimes very scary to do.

And I doubt I’d have done it if not for the COVID-19 pandemic. During that time, I felt like every time I read news or research or anything public regarding the novel coronavirus, I would see the words diabetic or diabetes and severe outcome or death within an inch or less of print on every page. Never before had I seen the name of my disease so frequently in the news—nor for such terrifying reasons. I didn’t really want to write about diabetes, nor did I have any desire to write about the COVID pandemic (it’s just too hard to say anything meaningful about something everyone is simultaneously experiencing but in so many different ways). But it was taking up so much real estate in my imagination, I eventually sort of succumbed to it. It was extremely difficult at first to be candid with myself as I wrote—and I figured if I was going to undertake writing about my experience with chronic disease, I had better at least be authentic about it and try to learn something from the experience. But as I worked on the language and became more and more invested in finding artistic strategies for transforming my subject matter, it got easier. Eventually, I really came to embrace the project and at that point, the writing got both easier and more interesting for me.

The artistic challenge—one that felt weirdly anathema to how I’ve worked as a writer up to now—was contending with how to manage the “aboutness” of the poems in a way that wasn’t absolutely boring to me. I have said in other interviews (and deeply meant it, and still mean it) that one doesn’t write poems because one has something to say, but rather because one has something one doesn’t know how to say. I knew I wanted to write about diabetes, and I honestly didn’t know what I wanted or needed to say about it—but I also knew that there was a certain amount of information that a reader might need in order to understand what I hoped I might end up writing about.

I hoped I would get deeply into the less-physical challenges of the chronic disease and explore its impact on the patient’s imagination—but to do so, it might help to know: What is diabetes? How does it work? What are its complications that make it so scary for patients with the disease? How is it treated? I didn’t feel I needed to provide a medical manual of all the knowledge about my condition that I’ve accrued over the years of managing it for myself, but I felt some basic exposition would be desirable. Trying to figure out how much, and where and when in the collection to introduce it, and in what form or through what trope—that was interesting and at times difficult.

And I honestly have no idea if I managed it well, but I tried to use different approaches—a “found” poem culled from The New York Times during the pandemic, a pantoum that I hope enacts some of the repetitiveness of the disease and having to explain my body constantly (especially with intimate partners), the conceptualization of a “haunting” and being haunted by one’s own body, a kind of not-sonnet love poem to the insulin pump that makes me (and I celebrate this) a cyborg, etc. My hope was that if I approached the subject matter in a kaleidoscopic enough way, a willing reader would be able to fill in the blanks. And I realized that if at times it felt a bit unrelenting or leaden, that was actually apt to the feeling of living with the condition, and I was sort of okay with it.

It was hard to write, and to be honest, there wasn’t a lot of joy for me in the process—but there was a lot of learning. And the most real gladness in this project has probably come from revision. I’ve never been against revision, exactly, but I don’t think I was particularly good at it, and I wasn’t sufficiently philosophical about it to make it work for me in a consistently meaningful way. My revision process before this project was sort of all-over-the-place and as often as not, if I couldn’t just triage a poem with some edits, I would abandon it. I did abandon many, many poems in the journey of this project, but I also realized at a certain point that I couldn’t abandon all of them or this project wouldn’t come into being at all.

So I became much more thoughtful and intentional about how I worked on poems after beginning them. I have always believed and continue to believe that the hardest work we do as writers—psychically, emotionally, intellectually, artistically—antecedes, precedes, and exceeds the page. So I learned that what I needed more than anything was just patience. I had to be kinder to myself. I would write a poem and go for a long walk with the piece in my head, and instead of worrying what I hated about it, I had to think about what I felt was important in it, and what wasn’t, and how it was falling short of my vision for it, and whether I should rethink my vision for it. I would show poems to my husband and sometimes even take his feedback into consideration. I would try different forms or different turns or different endings or beginnings in draft after draft, working slowly, poem by poem, word by word, until something felt . . . right.

I tried to listen to the poems and follow them where they wanted to lead me. It felt like it took forever to learn to just follow my instincts around a changing world with a changing heart. So maybe the greatest gladness and the thing I’m most grateful for in the writing of this book, really, has been time. Having time, and taking the time.

You taught a wonderful graduate seminar focused on the sentence a couple of semesters ago, and I feel lucky to have taken it! You remark, in another interview, that you wanted the overall organization of the book to feel “less chronological and more suspended-in-time-and-space,” in part to reflect the sense of nonlinear time people with chronic diseases and disabilities experience. I see this sense of suspended time down to more discrete layers of language: in the poetic forms you use, in your lines and sentences. I would love to hear from you: could you speak more on your use of the line in facilitating or subverting time in the book? The sentence? How do the two work in concert with one another?

What a fantastic question! (Also, I’m SO glad to hear you feel like you got something out of that class.) I’m obsessed with sentences, and I think about them a great deal, as you well know. There are many units of meaning in a written work (the word, perhaps even the syllable; the line), but the sentence fascinates me because we have somehow collectively agreed upon illusions of things like closure or completeness that it provides, and we feel it’s a gesture in time as well (although as signs marked on a page, it’s really an object in space). Sentences place words in relation to one another in a way that changes them and imbues them with specificity. And the ways we meaning-make in sentences has a great deal to do with our own expectations, too, which means they can be the source of much satisfaction (when expectations are fulfilled or exceeded) and also much surprise (when they’re subverted or disrupted somehow).

There’s so much to think about with sentences. I think about the many ways that syntax (a word serving as a subject and another as a verb, plus or minus any kind of modification) can create the sense of time speeding up (summary, exposition) or slowing down (scene, description, elaboration). And the kind of sentence (declaration, question, imperative, observation) can do so much, too, for how a poem “seems”—Walt Whitman’s long declarative sentences feel rather epic and sort of performative to me, while Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s long contemplative sentences feel deeply intimate, like thinking someone else’s thoughts. Emily Dickinson and Gwendolyn Brooks both sometimes write very short sentences that are so impactful emotionally, partly because they’re “in disguise” as something smaller or shorter—a kind of formal understatement that belies the poem’s sublime power. And I think of how much it thrilled me when one day, as poetry editor of The Cincinnati Review, I came upon a Dorothy Chan poem that was a little over a page long and was successfully written in one very long but grammatically correct single sentence.

But I also think a great deal about how poems can deliberately eschew syntax and sentence and rely upon fragment or punctuation-less flow. In such poems, time can feel thwarted or suspended or can feel like it moves in kind of unnatural starts-and-stops that call our particular attention to that slow motion or time-lapse or stop-motion animation of the language. And of course, one of the coolest tools in the poetry toolbox is enjambment, the suspense we create in a poem by drawing a sentence out over multiple lines. Sometimes we deliberately deprive ourselves of that particular “trick of the trade,” though, either by writing without traditional sentences, or in the case of the prose poem, writing without traditional lines. And both of those things call extra attention to the way the poem moves—or perhaps doesn’t.

So when I’m thinking about how time works for someone like me, I become super aware of how much of our sense of time in the world and on the page is related to how closely we’re paying attention to something. Sometimes, if I’m doing something like writing a poem or reading a book, I get in a “zone” if you will, and I feel somewhat out-of-time-and-space. I become distracted from the passage of time, look up, and find I’m surprised to note the sun has gone down. But more often than not, my disease requires a lot of my attention and fairly closely paid attention at that. Time slows way down, for instance, as I treat a low blood sugar in observed three- and five- and fifteen-minute intervals of anxiety and concern, or as I wait for a high blood sugar that’s making me really thirsty and sleepy, to come down safely over the course of an hour or two, or how time slows when I’m changing out my insulin pump and I cannot afford to make any kind of mistake in the process. I devote a lot of time and focus in any given day to some need my body has that I cannot ignore, and I’m very aware of that time. I think I’m also very aware of time on a larger scale, as something I have a finite amount of and I do not want to waste a single moment of—how that awareness makes me want to be, as I think Henry James called it, “one upon whom nothing is lost.” That, too, is a different relationship to the world and my sense of being in it.

So how does that appear in the poems of this book? I think a lot of the poems in this book are rather long and are composed of rather long lines and sentences, and in many cases, I think I’m trying to slow myself down. This might seem strange, but while I was writing this book the sustaining pedal on my piano broke, so I couldn’t really play much other than Bach. I missed so much the romantic sound of Debussy and Chopin, which require that pedal to draw out a single note for a longer time. I missed it so much I think I inadvertently tried to find that “sustaining” feeling and sound in the poems of the book, to find ways to draw the poems out more. To stay with an idea or a feeling for awhile, almost to exhaust it, as in the “Ode to Anthony Bourdain” or “At Teufelsberg in the Subjunctive Mood”—speaking of sentences, that second poem is really about how syntax and feeling cocreate each other.

Then there are prose poems that I think of as moving in a kind of breathless rush—either feeling a bit panicky or a bit ecstatic or maybe both, as in “Introduction to a Poem at a Reading.” Then there are poems (both lineated and prose poems) in the book that are written in fairly fragmentary ways, and I often think of those as being sort of frustrated movement, poems that want to move forward but have their flow constantly interrupted, as in “Discourses of Diabetes Care,” which I think of as a very frustrated poem, one that keeps tripping over itself. Or like the “He Asks Me to Send Him Some Words . . .” poems, which are about a love and longing for presence that’s interrupted by distance but also weirdly more intimate as a result of having to send so much language about that love across that distance to keep it healthy.

Sometimes the construction of syntax in the poems is really, really intentional— sometimes it’s much more intuitive. In the “Studies from Childhood” poems, for instance, I knew I did not want the poems to sound childish or juvenile, but I did want them to feel closer to inhabiting the perspective and memory of childhood. The best way I could think to strike that balance was to write in a mostly very uncomplicated syntax—short, right-branching sentences for the most part. Not a lot of dependent clauses. Not a lot of grammatical flourishes.

But in other poems, like “Clockwork Girl,” though also a reflection on childhood, I wanted the syntax and language to feel weirder and more elaborate to enact the idea that trauma can be really complex and defamiliarizing. I did not, however, recognize that I was doing any of those things in those poems until after I’d drafted them and I was working on revising them and someone gave me advice, and I found myself then thinking deeply about why I was so resistant to the advice. In trying to find a way to both articulate that feeling and then, eventually, turn that into a kind of writerly self-awareness that could guide me through the continuation of the poems, I came to understand why I wanted the syntax a certain way, and then leaned into it.

I could write so many more sentences about sentences, but I think I’ll just conclude for now by noting that I theorize sentences (syntax, anyway) as perhaps the most important way into a poem as a writer or as a reader. The way that poets use syntax and generate sentences (or do not) produces not only a sense of movement or slowness, quietness or loudness, or relative public-ness versus relative intimacy—though I think syntax contributes heavily to the construction of all of those things. But I think it’s very crucial to note how any given poet’s construction of their own syntax matters so significantly to that elusive quality we sometimes refer to as “voice.” I could never mistake an Anne Carson sentence for a Nathaniel Mackey sentence, for example. Nor an Ada Limón sentence for a Lyn Hejinian sentence. I hope that makes sense.

I am struck by the list poems in Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible. Notably, you end each section with a list poem, one of the “He Asks Me to Send Him Some Words . . .” poems mentioned above. Cumulatively, the poems shuttle between the speaker’s world and the beloved’s world; they feel intimate, as you note. More generally, I will observe that you seem drawn to listing and cataloguing across your body of work: in this book, certainly, but also in The Logan Notebooks and Love, An Index. Could you speak more about the poetic impulse to catalogue and the organizational logic of a list?

Oh, Andy, you understand me so well. I love a list poem, I really do. I fall hard for them. And there are so many ways to make a good list—I love Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” and as many who know me know, I am obsessed with The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon. I love the poem “Prayer (I)” by George Herbert, and Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You” and Harryette Mullen’s “Jinglejangle” and Craig Arnold’s “A Ubiquity of Sparrows” or his “The Invisible Birds of Central America” and so many more. Indeed, thinking about this, perhaps I’ll teach my next forms course on list poems! I would have so much fun. And they’re difficult to write well, but they provide the writer with so many advantages. Most importantly, they’re specific, expansive, and nonnarrative. Their logic is that of association and juxtaposition, which makes them feel intensely lyrical, I think. And they provide so many opportunities for fabulous imagery—and I am a total sucker for a startling image.

In my first book, Love, an Index, the impulse to list and catalog arose as a way to solve a couple of really important problems. First, I was trying to tell a story I knew could never be complete. First, no story can ever be complete. Second, the person who shared the story I was trying to tell had died and would never get to tell his version. Third, the logic of narrative is a logic of cause-and-effect, action-and-consequence, and when you’re telling a story about a death, that logic can lead down terrible rabbit holes of what-if’s and if-only’s that only result in guilt and shame and blame and doubt that nobody needs or wants or deserves. So footnotes, indexes, those allowed me to create repositories of certain important memories or moments or objects or ideas that could hold and keep the story I was trying to tell in a series of significant and signifying fragments without any of that “cause-and-effect” baloney.

The idea of an index, a footnote, and other forms of “gloss” probably came to me because I was reading for my doctoral exams at the time and I was immersed in appendices and annotations constantly, but it also did the work for me of suggesting a much bigger and larger story—unwritten and unwritable—to which the poems referred but which would never exist. Finally, I think the forms suggested something very academic, which was a nice foil to the fact I was writing deeply emotional elegies—both amatory elegies and elegies of mourning (as those two are almost two sides of one coin). The cruel separation of Eros and Psyche plays a large role in that book; I thought marriage of the form and content in some of my poems could help restore them together a little.

The Logan Notebooks is really heavily, heavily inspired by The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon, and many of the poems in the collection are imagined as zuihitsu. I reached for that form when I needed to stop writing elegies because I found it to be a form that lent itself very much to presence—it’s a highly observational form and I needed to just write about the very everyday things of the world around me to keep myself present in it. Zuihitsu are, I think, most effective when they’re largely concrete, highly specific poems of rigorous attention, poems in which the poet’s imagination is very focused on a deep, authentic mining of the real for its wondrousness.

In keeping with Sei Shōnagon (as I understand her; I have only read the book in its translations into English), the presence of the writer in the poem is also primarily as a lens—a fabulously opinionated lens and a highly unique voice—but the form allows the writer to hide in plain sight. Zuihitsu is both deeply intimate, and wonderfully concealing, in that it constructs the reader as one who has stumbled upon the author’s most intimate thoughts, but it’s also a form that encourages the writer to curate those thoughts with utmost care. And from the lists and anecdotes collected in a book like The Pillow Book, a whole world slowly emerges—this, too, gives the impression of storytelling without requiring narrative logic.

But list poems are challenging to write because even though they’re lists, they suggest assertions (in a list of “Hateful Things,” for instance, there’s a suggestion about what “hate” is and what “hateful” means), and characters and places emerge with strong emotions evoked around them. There has to be some kind of “turn” even in a list poem—poems should move. There should be syntactical repetition, but also variation and surprise. There should be image, but also rhythm and interesting, thoughtful sounds in the language. You have to think carefully about transitions by association, juxtaposition (abstract and concrete, for instance), by graphic match or sonic similarity. And the end, somehow, has to feel like a natural stopping point, which can be tricky in lists. But man, if the writer pulls it off, it’s such a gratifying experience.

So I think probably the list poems in Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible got themselves written for many of the reasons the other list poems I’ve written did, plus I think having now written so many of them, I have a kind of impulse to do so from time to time. I enjoy writing lists; I find them clarifying, and I like the chance to play with the various ways they can surprise both the writer and the reader. I like the logic of the form, I appreciate the ways I can play with imagery both abstract and concrete in the form, I like that they’re really visceral but also very existential poems, I appreciate that I can be fully present in but am not the actual subject of the list poems, and I love them as ways of cataloguing memory and experience and idea and wish. One of these days, I hope to write a book that does not involve deep, lasting trauma, but I don’t think I will ever stop writing list poems. They’re a source of real joy for me.

So much of Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible responds to the material world and the ruinous remnants of the world; you write in response to Incan ruins, Irish ruins, and ruins elsewhere in the world. I would like to end with a question on influence: What were the objects, artifacts, or works of art (broadly defined: visual art, music, architecture, etc.) that were in your orbit when writing the book but did not make it to the book directly?

I love this question. It’s so important and I don’t think such questions get asked often enough. Visual art is a huge part of my practice as a poet. While I’m not a visual artist AT ALL, I was raised by one (my mother). Some of my earliest memories are of being carted around art museums in my stroller; I recall and have been told many times that I was most compelled as a wee one by what I called “the Jesus paintings,” images of the crucifixion. I don’t think this is because I was a particularly mystical child but because I was a bit of a morbid one—the blood from the crown of thorns, the very realistic renderings of nails through hands or wrists and feet, the anguish on the faces of the believers: I think I found it all to be highly dramatic. (I suppose I still do.)

I was traveling on an Amy Lowell Poetry Travelling Scholarship when I began working on these poems and taking notes for them, so I had the incredible opportunity to make art pilgrimages all over the world—to Cusco, to Buenos Aires, to Berlin, to Paris, to Rome, to Minneapolis, to various galleries and exhibitions right here in Cincinnati. So many, many things moved and changed me during that time, but there’s one I’ve not yet found a way to write about that’s been very important to me. I went with my parents to an exhibit at the Centre Pompidou in Paris—it was the most comprehensive collection of van Gogh’s paintings that I had ever seen, and it was curated alongside the writings of Antonin Artaud, so as to highlight questions of mental illness and mental anguish in the work of both men. I had never before seen van Gogh’s brushstrokes as being a reflection of such agitas, and in particular I recall a painting —a very unstill still life—of a coral-pink crab on its back, the background of the work being just a field of cyan blue. And it was such an image of vulnerability, it really left me thinking about that state of being (vulnerability) and the combination of suffering and self-knowledge that accompany it.

I also started thinking a lot, due to the curation of that exhibit, of what we mean by “success” and “failure” in art, especially art of personal expression. And that thinking has really helped me feel both more brave and more grounded as a poet and as a human, and I don’t think I could have written this book without having had time to really decide what “failure” means to me, and how important it is to fail and then (to cite one of my favorite Beckett moments) fail better. I hope this goes some way to answering your question—I’ll still be thinking about it long after this interview is published, though. I feel there is much, much more I could (eventually) say. So thank you!

Rebecca Lindenberg is a writer, educator, and editor. She’s the author of Our Splendid Failure to Do the Impossible (BOA Editions, 2024); The Logan Notebooks (Mountain West Poetry Series, 2014), winner of the 2015 Utah Book Award; and Love, an Index (McSweeney’s 2012). She’s the recipient of an Ohio Arts Council Individual Artist Excellence Award, an Amy Lowell Traveling Poetry Scholarship, a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Grant, and a Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Prize, among others. She has also been a Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and the MacDowell Arts Colony. Her poetry, lyric essays, and criticism appear in The Missouri Review, Poem-a-Day from the Academy of American Poets, The Best American Poetry 2019, Poetry, The Believer, Tin House, American Poetry Review, Tupelo Quarterly, McSweeney’s Quarterly, The Journal, Seneca Review, Prelude, DIAGRAM, Third Coast, Smartish Pace, Conjunctions, Iowa Review, and elsewhere. She is an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati, where she is also Poetry Editor of The Cincinnati Review.