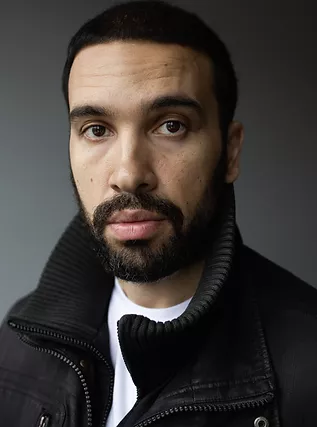

Our current issue, Issue 18.2, as you might have seen, includes photographs by Marcus Jackson. We’ve published his poems in the past, in issues 6.1 and 16.1, but Poetry Editor Rebecca Lindenberg knew that he’s also a serious photographer and reached out to him about the CR featuring his art in our fall 2021 issue. As Jackson describes in a recent Columbus Monthly piece, when he and his wife bought a camera as new parents, to document the changing stages of their child’s life, “my path toward comprehending the strengths and quirks of that camera and of other gear […] began a nearly decadelong journey that remains ongoing, a journey that has earned me invaluable reckonings, mistakes, and enchantments.”

In the artist’s statement that accompanies the portfolio of his work in the issue, Jackson also explains how he chooses subjects:

As an African American photographer, I prioritize making space for the moments and the people whose essences represent the ongoing interplay between history, society, and the individual soul. While making black-and-white portraits in public places with natural or available light and choosing subjects who are in motion or going about their daily lives, I invite the resonant exchanges between public circumstances and private consciousness and emotion.

We’ve included some images from the portfolio in this post, but you can check out more of his work online on his website and on Instagram. As we worked on the issue, we were intrigued by the strength of both his photography and poetry, and Associate Editor Lisa Low asked him about both his forms of art recently:

How do your photography and poetry work interact?

The most obvious interaction across my work in both art forms is the setting, which is usually urban. I was born and raised in a Rust Belt city, and I lived in New York City for years, so the streets are dear to me, and they constantly surface and host the poems and the photos I make. My work in either form is likely drawn to the streets because that’s where so many of my memories and my selfhood lie, and that’s also where I still encounter innumerable intriguing people, scenes, and revelations about society, culture, and the echoes of history.

How are the two art forms similar to and different from each other in terms of the ways you think about them, how they operate craft-wise? What does one form teach you about the other?

Both forms call upon the act of distilling and coalescing subjects, elements, and narratives to their most dynamic, potent, motion-filled versions. Since the forms have an expectation for brevity and/or urgency, photos and poems have the challenging task of trying to impact their audience quickly while also trying to fill with enough details and energies to still be able to surprise their audiences in subsequent viewings/readings and, hopefully, to make their audiences feel reluctant to turn away from them at all. Both forms teach me, even when I fail at them, how time and care in the creation process eventually lead to unique, crucial work.

What is your favorite part of the photography process? The most challenging?

I have a lot of favorites: walking the streets and getting a feel for the moods of neighborhoods and of people; paying ongoing attention to all the ways natural light shifts, and then letting the light and the shadows of certain locales tell me where and when to press the shutter button; manually focusing a camera’s lens, which feels like wiping a smudge away from a jewel; making an archival print and knowing that a fraction of a second has now become an artifact with an independent life and identity.

The most challenging aspect is disconnecting from the obligations and worries of life (which nowadays can menace us electronically and virtually) for enough time to allow myself complete concentration and permission to dream of and anticipate photos that have not been made yet.

Can you talk us through the process behind one of the photos included in your series in Issue 18.2?

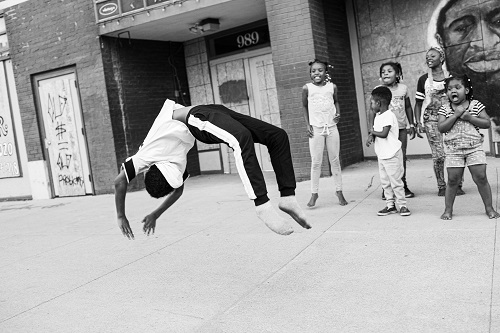

The memory of making the photo Shoeless Acrobatics on High Street, 2020 remains important to me. At summer’s end in 2020, during yet another national gut-wrenching reckoning with police brutality, while simultaneously mourning multiple unarmed Black folks slain by officers, and after months of protesting, leading into the belly of a presidential election I assumed would yield more injustice and peril, I walked a busy street in Columbus, Ohio, on a humid evening, and I heard music a couple blocks ahead—a live set of drums. On the corner of the music’s making was a child, about ten years old, playing a full drum set prodigiously, and seven other children, from the ages of five to twelve, danced to the exact choreography shouted by one of their mothers or guardians, who called out turns, steps, leaps, and song changes from a few meters away.

A country’s worth of venom and brutality, because of these kids, fell briefly away from many who watched them dance and play drums that evening. For two songs, with the permission of the parent/guardian leading them, I got on my knees with my camera and wide angle lens and tried to make some photos of the children’s brilliance and fearlessness. The oldest three dancers were extremely skilled, blending ballet and hip-hop, barefoot or in socks on the pavement. One of the oldest children did a sequence of back handsprings into a backflip, and the photo previously mentioned is of that child in midair. The windows of that corner were boarded with plywood whose murals grieved and vowed. These children, taking turns soloing and cheering each other on, made any story of heaven I ever heard bow its head and become dust.

Marcus Jackson is a poet and photographer who holds an MFA from New York University. Jackson is the author of two books of poems, Pardon My Heart (Triquarterly, 2018) and Neighborhood Register (CavanKerry Press, 2011)m and his work has appeared in such publications as American Poetry Review, the New Yorker, and New York Times Magazine. Jackson teaches at Ohio State University.