Interview with John Philip Drury

13 Minutes Read Time

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: As a doctoral student here at the University of Cincinnati, I took a poetry workshop during my final year, while I was working on my dissertation. It’s an odd choice for a time when most people are focusing on that final, cumulative work, but I did so for three reasons: John Drury, my dissertation adviser, was teaching the class; he was running it as a generative workshop, including a two-week poem-a-day stint; and each week we’d approach our class workshop in a different way, so we learned about pedagogy at the same time. See more about that class below. It was one of the best workshop experiences of my life, and I wrote a good chunk of my dissertation manuscript, which evolved into my second book, Romances, in it. Even more so, though, it meant more time with John, who is one of the best human beings on the planet: generous, smart, kind, funny, and good-hearted.

So we’re glad to share the news that this great human and poet has a new book out this week, The Teller’s Cage with Able Muse Press! He’ll be launching the book with a reading at Joseph-Beth bookstore on Thursday, January 18, at 7 p.m. It’s a fantastic book that explores the roles of son, father, and husband; includes everything from sonnets to long narrative sequences; and ends with a fascinating section of production notes for imaginary movies based on the poems.

I reached out to John to ask him about the book itself, teaching, social media, and more:

What was the best or easiest part of writing The Teller’s Cage? And, if applicable, what was the hardest or most challenging part of writing it?

The best part of writing The Teller’s Cage was that I had a decade in which to develop the collection. The most challenging part was figuring out exactly how to develop it—what to add, remove, revise, and rearrange.

I envy poets who are able to start a book with a clear vision of where it’s going and then to write poems that contribute to that vision. Louise Glück is my favorite example of such a poet. My own writing process, in terms of putting books together, has been far messier. The root of the problem is that it took me twenty years after I received my MFA at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop to get my first full-length poetry collection, The Disappearing Town (Miami University Press, 2000), published. All that time, I was writing new poems and trying out different arrangements. At one point I had four collections in progress, including a book of Pindaric odes.

One of the poems in The Teller’s Cage, “The Electric Guitarist,” tells the story of how an Iowa classmate, Jim Simmerman, persuaded his editor, James Reiss, to consider my first book for Miami University Press, even though the series specialized in second books and beyond. He made an exception for me. Since I had a backlog of unpublished poetry collections, it was just three years later that he published my second book, Burning the Aspern Papers (Miami University Press, 2003).

And a book-length sequence, The Refugee Camp, won the Paris Review Prize and was supposed to be published in 2006 by Zoo Press, but the publisher suddenly went out of business, a fiasco covered by an article in Poets & Writers, “The Collapse of Neil Azevedo’s Zoo.” So I had to search for a new publisher for that sequence. Meanwhile, I was already circulating another manuscript, then titled Circle Line after a crown of sonnets it contained. After The Refugee Camp was finally published in 2011 by Turning Point, I could devote my full attention to revising, rearranging, and continuing to submit that fourth collection, which was published as Sea Level Rising by Able Muse Press in 2015.

But my works in progress continued to overlap. In the fall of 2012, I went on a hot streak and wrote twenty-three new poems in two weeks, but I never considered adding them to the collection I was working on. From the beginning, they seemed like the basis for a new book—or possibly multiple books—mainly because they included five “imaginary movies,” adding up to fifteen pages in typescript. For a couple of years, the filename for this nascent collection was “New Book in Progress.” But then, around the time when Sea Level Rising came out, I split the manuscript into two separate collections-in-progress, The Teller’s Cage and Imaginary Movies.

A couple of years later, after writing just one more imaginary movie, I combined the manuscripts into The Teller’s Cage, which I then revised and reordered for several years, trying out different arrangements until I reached the six-section book that’s now being published. I deleted two of the imaginary movies, although I’m happy that one of them, “How to Remake My Favorite Wife (1940),” is forthcoming from Gargoyle and has a place in my latest “New Poetry Collection in Progress,” which already contains seventy-nine pages of poetry, including a section of translations, but will certainly require several years of fiddling and fixing before it’s ready to submit.

I think this is the first time I’ve seen a poetry collection that includes a section of production notes for how filmmakers might produce the poems as movies. What inspired you to go in that direction?

My secret hope was that some filmmaker or screenwriter would want to use one of my imaginary movies as the basis for an actual film. But a good deal of research went into those poems, and I wanted to acknowledge their sources, especially for “The Ruined Aristocrat.” I also had fun putting the production notes together. For “Streets Full of Water,” it gave me a chance to name characters who appear in the poem. For “Chaconne,” I wanted to give credit for the story about the murdered composer told by Suzanne Bona, the host of the radio show Sunday Baroque. One of the book’s epigraphs is by Alfred Hitchcock, whose quotation I found in François Truffaut’s marvelous book of interviews with the director. And two of the other poems, “The Poet as a Seven-Year-Old Baseball Fan” and “The Projectionist,” also refer to movie-making.

The poem “Social Networking” addresses life on Facebook—

Facebook, for me, is not much fun,

as public as a nudist colony

where I have nothing on,

like a bad dream in which onlookers see

my tongue-tied shyness magnified.

Exposure makes me blush.

In your experience, how is writing about personal experiences in poetry different from the way a writer’s life gets shared on social media?

When I wrote the batch of poems that formed the nucleus of The Teller’s Cage, I had been on Facebook for just a couple of years. I originally joined because The Refugee Camp was coming out, and I thought I needed to publicize it. From the beginning, I had misgivings about Facebook, partly because I’ve always been shy (hence the reference to “my tongue-tied shyness”), partly because I’ve never been comfortable about joining clubs. I’m also conflict-averse, and the squabbles that flare up on social media really bother me. In a poem, personal experience has to be transformed into art, no matter how transparently the story is presented. Since I’m primarily a narrative poet, the concision and musicality of the storytelling is very important to me. Most posts on Facebook come across as news flashes, even if they’re about what the poster prepared for dinner (I recently posted a photo of a pan of spanakopita I had made, using the recipe of my ex-wife, to whom the poem “Windfall in Baltimore” is dedicated). But some poets, like my friend and Iowa classmate Steve Kuusisto, do post new poems directly on Facebook, and I love seeing them there. I also like both seeing the poems of friends that have been published online and sharing my own. As time has passed, I’ve grown to love Facebook for the connections it makes possible, the old friends recovered and the new friends just made. One other advantage is that it’s often easier to get in touch with someone via Facebook Messenger, since email addresses are harder and harder to find.

In your acknowledgments, you describe how one of the poems was generated in a graduate seminar on “The Sources of Poetry.” How does your teaching inform your writing? (I realize that you’re retired and so the verb there should be past tense, but I have a feeling you’re still teaching in other ways!)

I shared the names of the students in that seminar because we had all participated in a word-list exercise (based on the assignment David Wagoner had given to a workshop that included Tess Gallagher, whose “The Horse in the Drugstore” is my favorite example of a word-list poem). Over the years, I have become a believer in my teacher Marvin Bell’s maxim, “Sometimes I think that the growth of a poet depends to some extent on his or her becoming less and less embarrassed about more and more.” So in my last years of teaching, I started to share poems I had written based on exercises I had assigned to my students.

That wasn’t the case in Fall Semester 2012, when I gave my graduate poetry workshop the assignment to write a poem a day for fifteen days. Lisa, you were a member of that class, and so were Brian Brodeur, Tasha Golden, Julia Koets, Dave Nielsen, Amy Ninneman, Michael Peterson, Linwood Rumney, Lisa Summe, and Sara Watson.

Here’s the prompt I gave: “On Sunday, October 7, we’ll begin a two-week period of writing a poem a day. We’ll finish on Sunday, October 21. If you have trouble generating material, ‘lower your standards,’ as William Stafford advises. Grab a traditional form. Describe an object. Talk about the view from your window (current or former). Recount a dream from last night—or years before. Indulge in some automatic writing. Versify something you’ve read or a news report on TV. Lay a curse on someone—or offer praise.” In the middle of that two-week period, we had an “oral workshop” (or “aural workshop,” since we had to concentrate on listening to what the poet read and then reread aloud, without being able to look at any text on the page or on the screen of the projector). At the end of the fifteen-day period of daily writing, we discussed the results en masse, and I asked everyone to give their fellow students lists of “keepers,” “maybes,” and “maybe nots.”

I started my own daily writing right after that discussion, but I don’t think I told anyone I was doing so, and I certainly didn’t share my results: twenty-three poems, of which thirteen turned out to be “keepers” (included in The Teller’s Cage), three were “maybes” (forthcoming in literary magazines and now in the queue for possible inclusion in my next book of poems), and seven were “maybe-nots” (poems I’m no longer submitting anywhere, consigned to the limbo of my flash drive).

I wrote other poems as in-class exercises, including “Listening to John Coltrane,” drafted in my Music & Poetry undergraduate course while we listened to the first movement of A Love Supreme. Another was “Curriculum Vitae,” based on a Lisel Mueller poem my wife, LaWanda Walters, passed out to a workshop we both led at Otterbein College (which happens to be the alma mater of my paternal grandmother and grandfather). I also wrote three poems when I substituted for Brian Brodeur in a three-hour summer class on Midwestern poets: my “Horseback Riding” (originally titled “1961”) responding to Weldon Kees’s “1926”; my “Cincinnati Haiku” responding to three haiku sequences by Etheridge Knight (and I later expanded my sequence, alternating 5-7-5 haiku with the 17-syllable monostichs used by Iowa classmate Marilyn Chin); my “Choosing a Reader” responding to Ted Kooser’s “Selecting a Reader.”

For my final sabbatical, which took place during Fall Semester 2016, I proposed an ambitious plan to compose seven new imaginary movies toward a collection devoted to them. I did preface my list of projects with a disclaimer: “In composing poems, there is always an element of surprise involved in the process. New ideas and sudden impulses will often supplant careful plans, since invention depends on new openings and sudden, unforeseen connections.”

In my report about the sabbatical, here’s how I explained why I wrote just one of those imaginary movies and abandoned the others:

My original plans, as outlined in the proposal, changed radically during the course of working on actual drafts. Originally titled “Divine” (after the cross-dressing star of the director’s early films such as Pink Flamingos), this poem about my mother, John Waters, and the ambergris found on a beach by a shipwrecked man who might have been our common ancestor [“The Ruined Aristocrat”] was my top priority, and it soon took over the entire project.

At this point, I was vacillating between either lumping eight imaginary movies into the central section of The Teller’s Cage or moving them into a separate manuscript called Movie Set. It wasn’t until February 16, 2019, that I rearranged The Teller’s Cage into six sections, each ending with an imaginary movie, the first five using phrases from individual poems as their titles and the last one replicating the book’s title. From that point, it was a matter of adding new poems (such as the villanelle “Library in a Dresser Drawer”) or recovering and revising old ones (such as “Windfall in Baltimore,” originally written as “Chestnuts” when I was attending the MA program at Johns Hopkins, revised for an anthology project that has yet to come to fruition). I revised that poem because the ending no longer sounded true—and because I hadn’t followed the advice I’d given to poetry students for years: “Names are as good as images.” So I got more specific and mentioned Baltimore, Charles Street, and Druid Hill Park. I was still learning from my own teaching.

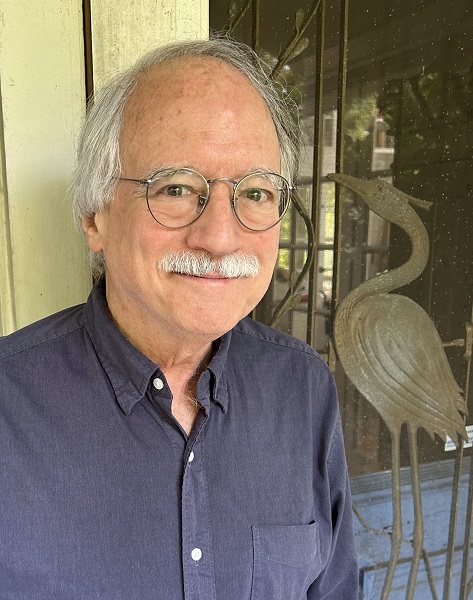

John Philip Drury is the author of six collections of poetry: The Stray Ghost (a chapbook-length sequence), The Disappearing Town, Burning the Aspern Papers, The Refugee Camp, Sea Level Rising, and The Teller’s Cage: Poems and Imaginary Movies (just published by Able Muse Press). He has also written Creating Poetry and The Poetry Dictionary. He taught at the University of Cincinnati for thirty-seven years and is now an emeritus professor.