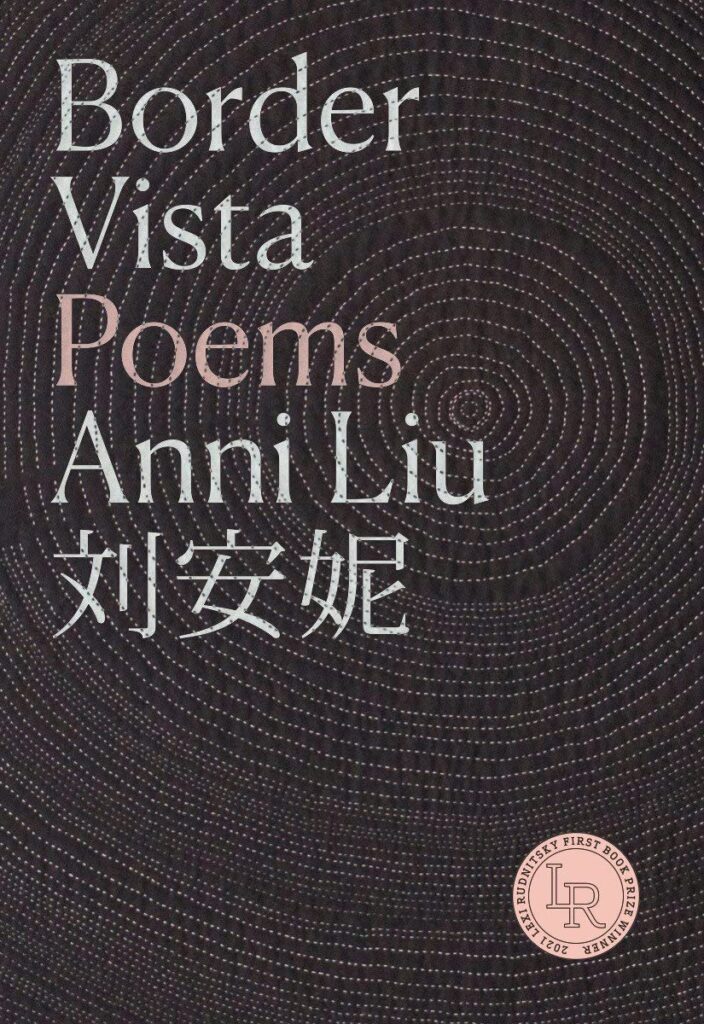

Associate Editor Lisa Low: Today continues part two of the interview exchange between contributors Anni Liu and Danni Quintos, whose debut collections share a book birthday (this past Tuesday)! Check out part one for a conversation on Quintos’s Two Brown Dots, and read on for Liu’s insights on the process of writing Border Vista, Janus words, ars poeticas, and undocumented joy. We hope you get to check out her work, both in our miCRo series as well as the collection itself! Happy book release, Anni!

Danni Quintos: Debut collections sometimes feel like, All the poems I like ‘til now (or at least that’s how mine feels). How many years does your collection span? Not the time featured within the poem, but the time drafted: which is your oldest poem (and how old?) and which is your newest?

Anni Liu: I think “Tracks” is the oldest poem in the book, drafted in 2014 or 2015, and there are a handful of other poems that are from that time, but most of the poems were written between 2016 and 2019. I spent most of 2020 revising Border Vista as a manuscript before submitting it to prizes. There are a few new poems that were written after that, the newest being “State Symbols,” which I completed in 2021.

Some of the best advice I’ve received was not to rush the first-book process, and since things move at a pretty rapid pace after you win a first-book prize, I’m really glad I gave myself so much time before submitting to sit with these poems.

DQ: I love how your collection opens with an ars poetica, which I have never written! How did you approach your ars poetica and/or whose work do/did you turn to for inspiration? (Do you have a favorite ars poetica? Mine is Aracelis Girmay’s “Arroz Poetica,” which makes me swoon.)

AL: When I wrote the first line of “Ars Poetica in a Dream Language” (“I dream my mother / unravels / hair out of my mouth”), I became curious about “unravel” and what I assumed would be its opposite, “ravel.” In the OED, I found that though it’s very rarely used, “ravel” is a word, and it also means “unravel,” making it a Janus word or a contranym, continuing its own opposite meaning. The OED also included obsolete meanings like “destroy,” and it struck me that at some point the word became unused or unusable because it had become too full of meaning. And obsolete meanings interest me, too, as they’re the past lives of a word, ghost meanings that ripple behind current usage. All of this resonated with my own wrestling with writing poems or even remembering in English, a process which has felt like all of the senses of ravel at different stages, destructive and violent, attentive and constitutive. The poem followed from there, leaning on the ambivalence and multiplicity of that word.

This is also a poem where I use slashes. These slashes (un)ravel the poetic line while also holding the poem together in the absence of other punctuation. They created mini line breaks that allowed for more double meanings and multiple readings of the line.

Because so much of the thinking behind this poem was about the act of writing, I called it an ars poetica. I remember my undergraduate professor, David Caplan, saying that every poem enacts an argument about poetry, what it is and how it ought to be (he also taught us to go to the dictionary, to know more thoroughly the words we choose). So in this sense almost every poem can be read as an implicit ars poetica. My favorite ars poetica not named as such might be Sharon Olds’s “I Go Back to May 1937” and its famous last line: “Do what you are going to do, and I will tell about it.” It’s such a bold statement of her task as a poet, and it was a formative poem for me. I love “Arroz Poetica” by Aracelis Girmay too, thank you for sharing that!

DQ: The third poem, “The Story,” participates in storytelling while also subverting storytelling expectations. Can you talk about your relationship with “storytelling,” and more specifically if/how you feel a responsibility to the original story or to the capital-T “Truth”?

AL: As someone who loves stories, telling and hearing them, the first expectations I had to subvert were my own. Early on, I didn’t know how to break out of the confessional mode. There is quite a bit of uncertainty and cloudiness around my personal and family history that I initially wanted to nail down in writing. I wanted company in remembering some painfully lonely experiences. I also wanted to risk a truthful accounting of my emotional life, something that might have been impossible without poetry. But eventually I felt it was just as powerful to speak and imagine into the gaps. So while most of my poems are autobiographical in some way, I don’t feel any responsibility to capital-T truth (and I’ve learned to be wary of that concept).

It has also been important to me to explore new ways of storytelling. Someone once said that we can only play when we feel safe, and I think that’s true to a large extent. My MFA was a space where playfulness was taken seriously, and where I felt encouraged to experiment. Because I was getting my MFA during the Trump presidency, when DACA was constantly threatened and we were being asked to legitimize it by speaking out, the stakes about what I was sharing felt quite high. Frustrated by some of the ways personal testimony was being used or consumed by the media (and seeing DREAMers being cast as the model minority of undocumented migrants), I began to attend more to questions about storytelling and identity formation through poetry/personal testimony. Subverting expectations felt more important than ever. I also started to write nonfiction where statements and arguments could be more baldly made, which returned me to what poetry does best for me: sounding, questioning, dreaming, and play.

Around that time I also got an Undocupoets Fellowship, and was blown away by this community and by the concept of undocumented joy. And for me, undocumented joy has everything to do with play, experiment, and subverting capital-T truth and narrative expectation. Like undocumented joy, we make room for all these things in our lives and in our writing despite our not being or feeling safe in the larger world.

DQ: I kept noting the repetition of hair, mouth, walls, false smiles, and I love how they often link or carry over into the next poem. Can you talk about order: chronology and narrative, and maybe how you decided on sections—breaks and categories?

AL: Thanks for noticing that! I only started to see those image threads after I started putting the poems together, and that helped me realize the cohesion of the book across time, subject, and place.

I initially organized the book in three parts, mostly chronologically: childhood, Vermont, then everything after. But as I articulated to myself the ways the book explores violence, absence, loneliness, storytelling, and embodiment, I wanted to let the poems call across their sections more clearly. Like you, I did a lot of rearranging after Persea accepted the book. I wanted the boundaries between the poems to be more porous. The second section felt particularly successful to me in that way, and I was glad to be able to put some poems about my own childhood (like “Demolished Landscape with Open Mouth” or “Six years old, my classmates and I”) next to poems about a stepson figure (“After School,””And I Looked Away”).

I hope the book reads like movements of a whole, where later strategies and moods are hinted at early on, and where the section breaks acts as breaths, not walls.

Anni Liu was born in Xī’ān in the year of the goat. She is the author of Border Vista, which won the 2021 Lexi Rudnitsky Prize from Persea Books, and her work is featured in Poetry, Ploughshares, Ecotone, Two Lines, and elsewhere. She received an inaugural Undocupoets Fellowship and was recently named a Djanikian Scholar by the Adroit Journal. She is currently working on a hybrid memoir about parole, translating the poetry of Dù Yá (度涯), and editing fiction and nonfiction at Graywolf Press.

Danni Quintos is the author of Two Brown Dots (BOA Editions, 2022), winner of the A. Poulin, Jr. Prize. She is a Kentuckian, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet.