Associate Editor Lisa Low: This week on the blog, we turn it over to contributors Anni Liu and Danni Quintos, whose debut collections both come out today! We love their work in our miCRo series—Liu’s “On Injury” and Quintos’s “Milkfish,” which also appear in their respective collections—and invited them to chat with each other as first-book cohort mates. Read on for Quintos’s take on the writing of Two Brown Dots, girlhood, parenthood, and literary and nonliterary influences, and stay tuned for part two on Thursday, when Quintos interviews Liu about her book, Border Vista!

Anni Liu: How did you start writing about girlhood, and how did your relationship to that subject evolve as you kept writing?

Danni Quintos: I think I started writing about girlhood in my girlhood, so when does girlhood end? I wrote a lot of poetry in high school, sort of wading in my recent memories of childhood. I think reading Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street made me want to embody my younger self’s voice. And then later in college I took a writing class with Steve Blakeslee (twice!), and I got real into Lynda Barry’s work and this idea of time traveling into your memories by using lists and images as entry points. And at Indiana University I was surrounded by incredible writers like T Clark and J. Franck who both write younger voices very, very well. I think I was influenced by their skill and humor and care with these younger versions of themselves. There’s a stickiness to certain ages in my memory; so many of my girlhood poems feel like they happen when I’m eleven or four, like there’s a dip in my brain and the memories all kind of gathered around those two ages.

AL: What was the process of ordering and arranging the poems in the book like for you, and how did the three-part structure come together? Could you say more about how the third part came to be called “Folklore”?

DQ: I did a very big overhaul of my book from the original manuscript I submitted to BOA. I’m so glad I was able to! I did so much rearranging between acceptance and publication, including adding more than ten poems. I got a lot of really helpful feedback from Aimee Nezhukumatathil, who chose my book and wrote the forward. Last summer I would often stay up later than everyone in my house so that I could spread out my poems on the floor and rearrange them from section to section. I am a very visual and tactile person, so I needed to see them laid out across my living room like giant Tetris pieces clicking into place.

I think the “Folklore” section sprung from my interest in family folklore and Philippine folktales. As a second/third (I say: 2.5) generation Asian American, so much of my connection to my Asian-ness is filtered through my grandmother, the stories she told me about our family (the poem, “The Oil Painting That Hangs on My Lola’s Wall”) and how she grew up. I am also interested in Philippine folktales (“Milkfish” and “Self-Portrait as Manananggal”) and recent Philippine history (“Letters to Imelda Marcos”); the way those three things sort of blend and braid together feel like the folklore of my FilAm identity.

AL: Who are the literary influences that you see most in your work? Were there poems by others that were key to your own growth?

DQ: I already mentioned Lynda Barry and Sandra Cisneros. I also see Ellen Hagan, Ross Gay, Aracelis Girmay, Nikky Finney, Mitchell Douglas, Kelly Norman Ellis, Patrick Rosal, Li-Young Lee in this collection. I feel like they are my literary older siblings, cousins, aunties, mentors, guides, idols.

I’m just gonna name one poem from each:

Ellen Hagan’s “Body Parts–Then”

Ross Gay’s “For Some Slight I Can’t Quite Recall”

Aracelis Girmay’s “To Waste My Hands”

Nikky Finney’s “Penguin, Mullet, Bread”

Mitchell L. H. Douglas’s “Tallahatchie”

Kelly Norman Ellis’s “Affrilachian”

Patrick Rosal’s “Delenda Undone”

Li-Young Lee’s “Persimmons”

AL: What nonliterary influences or practices informed your work the most?

DQ: Drawing, making comics with J. Franck, knitting, teaching, parenting.

AL: Your poems take a variety of forms, from the prose poem to the musical playlist to the epistle. How does the form of a poem take shape during your drafting process?

DQ: I write all first drafts by hand on the page. I do all my editing on my computer, so that’s when the form shifts, if it shifts. My poem about lactating after birth, “First Milk,” started as a prose poem, and someone suggested couplets. The playlist poem was always a playlist side-by-side poem, while the epistle was a whole chapbook that became a series of letters.

AL: I loved how in the two haibun, readers get a peek into how you use naptime for reading poems—and maybe for writing them too? What has writing been like for you after becoming a parent, and how do you build and sustain a literary practice?

DQ: I don’t know! I didn’t write for like two years after my kid was born. Then, I started a new job where I had summers off, and the pandemic started at the same time. Those two things, along with my kid getting bigger, gave me more time and brainspace to get back to my writing self. I honestly didn’t know if I was going to write poems again after I had my kid, and I had a lot of guilt about it.

I wish often that I were one of those disciplined writers who makes consistent writing time for themselves, even reading time. No, I’m a messy person who tries really hard to be neater. I clean all parts of my house simultaneously and frantically. I write when the idea hits me and there’s a pen and paper around. If I’m lucky I get hit with a poem or idea and I can write it down. I keep a little book with me in case this happens and I don’t have time to write the poem, just the seed of the poem. Sometimes my kid screams in my face or I have to wipe his butt before I get to write it down, and the poem disappears like an Etch A Sketch image. Sometimes the messy note I jotted down doesn’t translate or spark the same poem or anything that makes sense. I just try to take it seriously when it hits me.

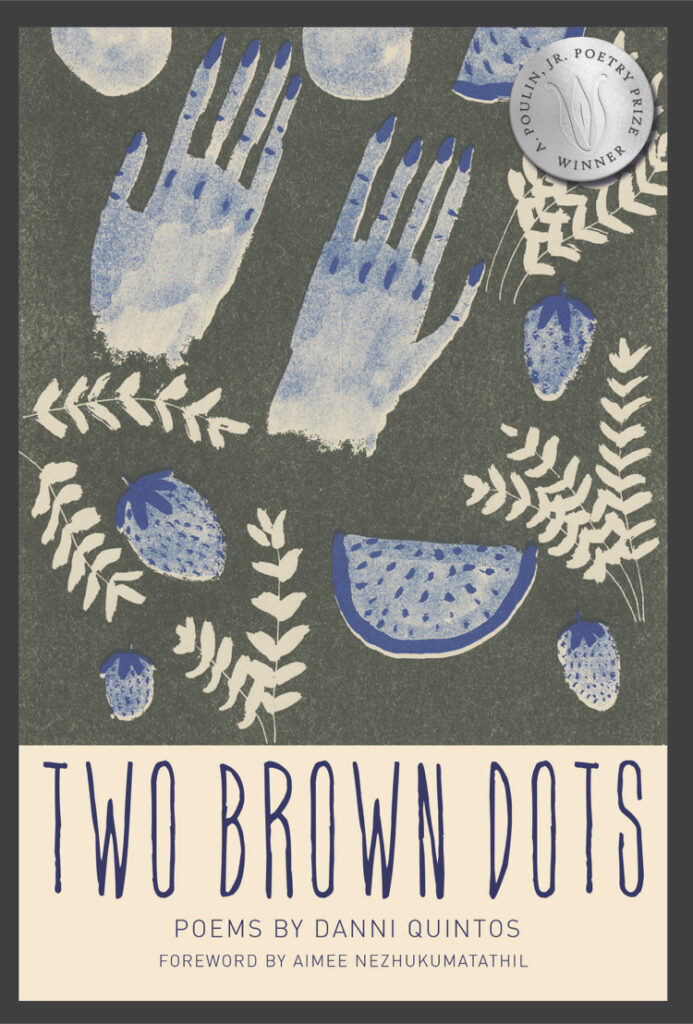

AL: Your cover art is stunning—could you talk a bit about how you found the art/artist and what it means to you?

DQ: Thank you! I love the cover art so much. Justine Kelley is a FilAm artist in Philadelphia. I found her on the FilAm Artist Directory when I was looking for cover art. I really wanted to have an Filipinx or Asian American artist do my cover, and especially because there are so many talented AAPI artists out there and it felt like the right fit for my collection.

I loved so many of Justine’s images! It was a little hard to choose. This one really struck me: the imagery, the sort of pretty uneasiness, bordering on creepy. The hands are my favorite part, how they’re reversed, how the fingers are uneven.

Danni Quintos is the author of Two Brown Dots (BOA Editions, 2022), winner of the A. Poulin, Jr. Prize. She is a Kentuckian, a knitter, and an Affrilachian Poet.

Anni Liu was born in Xī’ān in the year of the goat. She is the author of Border Vista, which won the 2021 Lexi Rudnitsky Prize from Persea Books, and her work is featured in Poetry, Ploughshares, Ecotone, Two Lines, and elsewhere. She received an inaugural Undocupoets Fellowship and was recently named a Djanikian Scholar by the Adroit Journal. She is currently working on a hybrid memoir about parole, translating the poetry of Dù Yá (度涯), and editing fiction and nonfiction at Graywolf Press.