In this column, I offer praise for the literary and the mundane, the startling and the run-of-the-mill.

Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman: As a voracious reader in my childhood, I picked up everything that seemed remotely interesting or new at the Florissant Valley Public Library. At some point in the early ’90s, I came across a YA hardback book called The Band Never Dances by J. D. Landis, published in 1989. In it, drummer Judy, in mourning for her brother, meets a David Bowie–like manager who sees her songwriting genius and recruits her to the band he’s building. They add a Carnegie Hall piano player, a jazz bassist, and the hunky guitarist/singer. Of course, they get famous, and there’s a love triangle, and the preteen in me who wanted to be a famous singer, songwriter, and/or actor loved every minute.

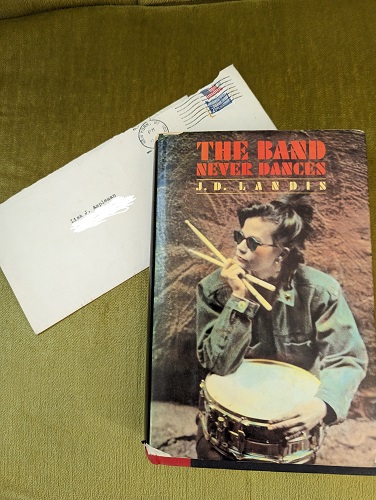

After that, I read every book of Landis’s I could find. In the days before the internet, I must have had my local bookstore order a copy of The Band Never Dances for me, because I still have it. And in the days before Facebook or Twitter or DMs or @s, I wrote J. D. Landis a fan letter—either by hand or on a typewriter (we didn’t yet have a computer)—and sent it to the address for Harper & Row Junior Books on the copyright page. I can’t remember the exact content, but I know I said that I liked his work and was thinking about being a writer, though acting and singing were also on my radar.

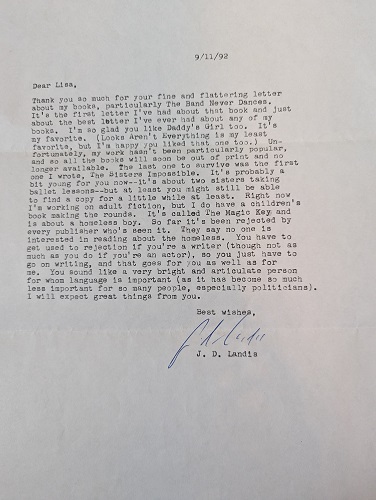

I didn’t expect him to, but he wrote me back in September 1992. The full note is below as text and image. Before I found the letter this week in my too-voluminous paper files, I remembered that he’d said the books weren’t doing as well as he’d hoped and that my letter was particularly cheering. Now as I reread it, I see that he was going to try writing adult fiction (spoiler alert: he did) and had one more children’s book to try to place (he didn’t).

In the end, I didn’t exactly become a songwriter, unless you think of poetry more broadly, I guess. My singing is best in a group, not as a soloist. But I keep writing fan letters to writers whose work particularly moves me—these days, most often by email or the contact form on their website.

I do so to share my joy with someone else who knows the work and tell them that I’m grateful for the imaginative work they did, but also to give the writer a sense that the text has landed with a reader. Landis’s response made me see writers as people who face rejection, do the work, and keep doing it even after setbacks. And now that I’m on the other side of the page, I know how energizing it can be to hear that something I made was read and admired.

Finally, something I didn’t know then: before he wrote me that letter, Landis had had a full career as a book editor and editor-in-chief at William Morrow. One of the books he found in the slush pile was Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I’m early in my editorial career, and haven’t acquired anything so iconic, but it’s a synchronicity that buoys me up.

And the tone I remembered from the letter, even before I found it again, is something I’ve felt at particular points of my career: When I’d been submitting my second book for more than four years without any nibbles or finalist mentions. When that book was published but just weeks before the 2020 pandemic shutdowns. When poems I loved failed to find homes in magazines. Each of these moments felt like failure—“my work hasn’t been particularly popular”—but that’s like ending a rom-com before the final confession of true love, judging an entire career by one data point. I can see it that way now (I’m sure I’ll forget that lesson at times in the future), that success is something else. It’s starting a writing career amid and after another career. It’s hearing from even one reader that your work reached them in some particular way. It’s encouraging others and participating in a larger community, and it’s keeping with the work no matter the current data trends.

Landis is active on Twitter. I’ve reached out to him about our correspondence in the 1990s. I haven’t heard back yet, but perhaps there will be a Part II for this essay.

9/11/92

Dear Lisa,

Thank you so much for your fine and flattering letter about my books, particularly The Band Never Dances. It’s the first letter I’ve had about that book and just about the best letter I’ve ever had about any of my books. I’m so glad you like Daddy’s Girl too. It’s my favorite. (Looks Aren’t Everything is my least favorite, but I’m happy you liked that one too.) Unfortunately, my work hasn’t been particularly popular, and so all the books will soon be out of print and no longer available. The last one to survive was the first one I wrote, The Sisters Impossible. It’s probably a bit young for you now—it’s about two sisters taking ballet lessons—but at least you might be able to find a copy for a little while at least. Right now I’m working on adult fiction, but I do have a children’s book making the rounds. It’s called The Magic Key and is about a homeless boy. So far it’s been rejected by every publisher who’s seen it. They say no one is interested in reading about the homeless. You have to get used to rejection if you’re a writer (though not as much as you do if you’re an actor), so you just have to go on writing, and that goes for you as well as for me. You sound like a very bright and articulate person for whom language is important (as it has become so much less important for so many people, especially politicians). I will expect great things from you.

Best wishes,

J. D. Landis