Associate Editor Lily Davenport: There is, suddenly, a lot of empty time. My dissertation defense was a week and a half ago. I passed, and am now officially the world’s most useless kind of doctor—and my body still isn’t used to the absence of this particular tension. I’m a very slow writer and was working on the first draft of my manuscript up until the hour I sent it to the committee; now, each morning at my designated get out of bed and write novel time, my eyes snap open, but I just roll over and wait for the adrenaline to fade. I feel the ghost of upwelling guilt when I read for pleasure (You don’t have time for this, idiot) that haunted my whole dissertation year, in the hours when I was too tired to write anymore but still had to feel like I was doing something writing-adjacent.

We’re past the equinox now, and the sun is going down a fraction later every day, but still the nights feel longer than they ever did when I was struggling to make it to the manuscript’s 200-page finish line. It’s not as if there’s nothing to do—my role here at the CR continues through the end of April, I’m getting ready to start a full-time administrative job at UC immediately afterward, and the specter of revisions to the manuscript (so I can turn it into an actual book, instead of only a dissertation) is beginning to loom larger and larger—but the central animating impulse of my day-to-day life, for the past year and then some, has vanished overnight.

Everyone has been telling me that I should use this time to rest; I’m certainly disengaging in a lot of ways, and probably look from the outside as if I’m resting, but all the while my brain is running on a loop: What can I do with this, what should I be writing right now, how can I turn this period of fallow exhaustion into something else. In the temporary absence of a project, I feel driven to reflect, to record, to make all the usual gestures of making sense of something.

What I’ve mostly been doing, instead, is something I already did (relatively) a lot of before my defense: playing video games. I had decided about a year in advance that my reward for finishing my dissertation was going to be a refurbished Nintendo Switch, and I ordered it the Friday before my submission deadline, knowing it would arrive the day I turned in the manuscript.

I had also picked out my first two games, several months beforehand: Sunless Sea (a game I’d previously played so much that it killed my laptop, which hadn’t been designed to run anything more strenuous than Google Chrome) and my all-time favorite, a game I had played for well over a hundred hours on my wife’s Xbox while listening to audiobooks from my exam lists, and which partially defines the exam and dissertation years in my memory: Hollow Knight.

For those of you who aren’t PhD burnouts, seasoned gamer bros, or teenagers: Hollow Knight, released by Australian indie studio Team Cherry in 2017, is a metroidvania soulslike in which you play as the Knight, a weird little bug with a crawling void under their shell, who carries a rusty nail for a sword. Translation: it’s a 2-D platforming game offering a mix of environmental exploration and challenging boss fights, in which new abilities or items unlock sections of the map that you’ve already glimpsed but couldn’t previously access (so you wind up going through the same areas multiple times, seeing new dimensions on each pass).

If you die, you have to return to where you were killed and defeat your own ghost in combat, while operating with reduced energy resources, to get your in-game money back; if you die again before you manage that—which is abundantly possible, given how far away some of the save points are from the hard-to-reach nooks and crannies where deaths tend to occur—your money’s gone for good.

The game is gorgeously animated and scored, with a huge map featuring lush backdrops, numerous hidden rooms, and cute-but-deadly enemies; the narrative is compelling but largely submerged, and the player is tasked with piecing it together from snippets of found text and enigmatic NPC commentary; the combat is famously difficult.

It is not, to all external appearances, a game I should like as much as I do. I came to gaming later than most of my peers, in the last year of my MFA, with Sunless Sea and its cousin Sunless Skies. For a few years my parameters were “no/minimal combat, no timed challenges, and I have to be able to play it on my laptop using the trackpad and keyboard.” I played the Sunless games that way, and Roadwarden, and Return of the Obra Dinn, and Cakes and Ale: all text-based (though Return is famous for its pixelated, woodcut-like graphics, and Sea and Skies involve piloting a vehicle across wild stretches of 2-D ocean or outer space, respectively), all foregrounding player choices as part of the storytelling, all of them more emotionally/intellectually than technically challenging.

I wasn’t good at games; in fact, I was, and still am, actively, catastrophically bad at them. I lack the muscle memory and intuitive sense of how to approach puzzles or enemies that most people in my age bracket accrued in childhood. (There are still huge swaths of the gaming world that I will probably never touch: anything first-person and 3-D is overwhelming to me on a technical level, since I will never be able to master walking with one joystick and looking around with the other.) My MFA friends, who had no such difficulties and played co-op Valheim or Deep Rock Galactic together several times a week, were somewhat puzzled by my issues, but supportive of the games I chose and the way I played them: alone, ineptly, fiercely, obsessively, with intense shame and fascination alike.

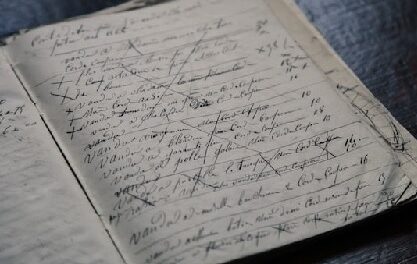

That’s the way I do everything I genuinely care about. It’s how I wrote my dissertation: in fits and starts, swearing out loud, determined and reluctant and squirmingly compulsive. I’ve been allowing myself to treat writing as a serious pursuit for ten years now, and in all that time I’ve never gotten any more at ease with the process than when I first started. I sound out every clause of every sentence in my head and don’t commit it to the page or screen until it’s fully formed; I go through endless half-made iterations along the way, each of them a tiny sting of wrongness, of embarrassment. But the accumulation of these little shames is, ultimately, a victory; those wins snowball, too gradually to be observed at doing it, into bigger ones. A paragraph, a scene, a chapter. Each one built of iterative shames, individual triumphs so small that they’re not visible until they’re stacked en masse.

Maybe I would have finished my dissertation sooner if I hadn’t played so much Hollow Knight. The idea that playing video games can make you better at writing novels is not, outside of a “getting a new perspective on character and narration” viewpoint, a sensible one on its face. But, without my fragile bug full of void, I don’t think I would have finished the dissertation at all. Gaming isn’t a restful thing for me; it’s cross-training for writing fiction, using the muscle of persistence-in-the-face-of-continual-failure in a slightly different way. I can’t say it’s taught me patience, or self-compassion, or problem-solving. Instead, gaming in general and Hollow Knight in particular have allowed me to practice failing and to normalize incremental progress, in an arena that isn’t so emotionally fraught, so deeply tied to my senses of self-concept and self-worth.

Both gaming and writing are practices in which past behavior is not the best predictor of future results; in my first Hollow Knight playthrough, it took me a full week to beat a boss called Hornet Sentinel, and at no point during that week was I even remotely aware that I was learning, that I was getting better. Every defeat felt just like the previous loss, and I was gloomily certain that this was going to be the end of my time with the game, that my reflexes were fundamentally too slow and I had hit a challenge that I physically could not pass. But then, one time, I didn’t lose; the Knight’s shell held together, kept the abyss it passes off for a soul caged inside for long enough to triumph. All it takes is one time. Even if your health bar is one hit away from extinguishing itself, even if you made mistakes along the way and took hits you should have dodged. It still counts. In fact, it’s all that counts.

I started over from scratch in Hollow Knight when the Switch arrived; I had dreaded fighting some of those bosses again and redoing several platforming challenges that had bedeviled me on the Xbox to get to the same late-game place where I had, my last time through, given up completely. But even with a new controller layout, my hands remembered enough to make things easier: I finished off the first three bosses in one round each, and Hornet Sentinel took me three days instead of seven.

There are still things I’m putting off—I haven’t gone back to the Watcher Knights battle yet or attempted the platforming challenges in the White Palace—but I’ve also accomplished a few tasks that eluded me last time, like liberating all forty-six of the adorable grubs that are trapped in glass jars scattered across the map. And I still get frustrated, and step away after one death too many in a row to the same hazard or boss; I know, all the same, that I’ll be back, probably after cussing at the air and watching someone a lot more skilled than me complete the same section of the game on YouTube. I know I’ve come too far not to see it through to the end.

I hope that this is what revising my dissertation into a real book is going to feel like: starting a new save file of a game I’ve played but never before finished, returning to familiar places on the map and knocking down the hidden walls to find new rooms within them. New controller, same enemies. I will spend most of my time getting it wrong; all I need is one time where I get it right.