Associate Editor Jess Jelsma Masterton: At The Cincinnati Review, we edit selected pieces with what we call “The Five C’s” in mind—clarity, conciseness, correctness, conformity, and consistency. In essence, we ask: Does this sentence (or plot point) make sense? Is there unnecessary repetition of a certain word or phrase? Are the facts correct? Do the grammar and usage conform to the Chicago Manual of Style? Do the rules of punctuation and logic hold true throughout? Outside of these C’s, we must also consider the author’s intentions and overall vision. Our job is not to change the author’s voice or style to reflect those of our editors, but to further elevate the piece in whatever small ways we can.

To think more about the role of a literary editor, I turned to our own Managing Editor Lisa Ampleman, who has experienced the process from both the author’s and editor’s perspectives.

Jess Jelsma Masterton: At present, you serve as the managing editor of The Cincinnati Review and the poetry series editor of Acre Books. Both positions involve reading submissions and working with selected authors throughout the editing, production, and promotion stages. What do you see as the primary role of a literary editor? What does an ideal relationship look like between an editor and an author, and how do you navigate editing work while remaining true to the author’s original intention or vision?

Lisa Ampleman: I often describe the role of editor as similar to that of midwife—we’re helping something come into the world, but it will not be our baby. The story/poem/essay is our author’s baby; we’re just assisting them in getting it into readers’ hands. It’s not a perfect metaphor, but it’s a start.

One of the tall tasks for those new to the editing profession is not to edit a piece in light of how they would write it, not to give the kinds of comments they would in a workshop. Instead, they should consider the text almost as if it were an assigned reading in a literature class, to think about what the author’s project is, and then edit keeping the author’s style and choices in mind. If a story is written in a maximalist vein, for example, we don’t want to cut down all the sentences so that they’re shorter, but we do want to make sure what’s there reads clearly, that it uses punctuation as skillfully as possible, even as it loops in more and more details and asides.

In fact, while we promote finished work, we need to have intention in mind too. For example, our spring 2020 poetry title for Acre, Elizabeth Lindsey Rogers’s The Tilt Torn Away from the Seasons, describes a human mission to Mars in light of climate destruction here on Earth. That latter piece is important to her—this isn’t just The Martian in verse—so we’ve kept that in mind as we make decisions about catalog copy, the cover, the video trailer, etc.

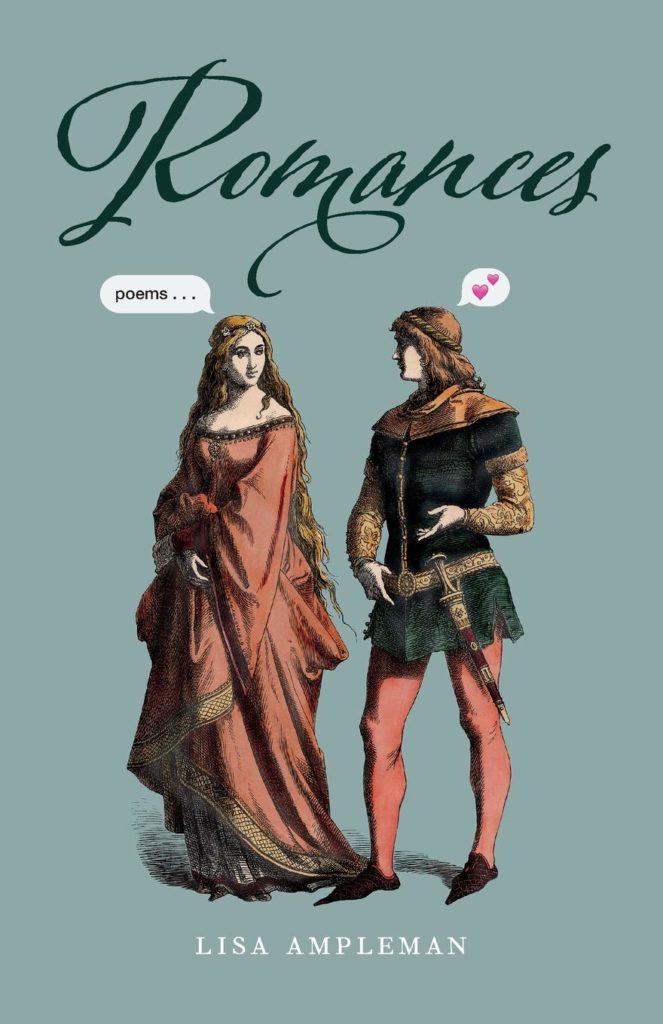

JJM: This February, your second full-length poetry book, Romances, is coming out through LSU Press. Your first book, Full Cry, was released through NFSPS Press in 2013 and your chapbook, I’ve Been Collecting This to Tell You, through Kent State University Press in 2012. Overall, what has your experience been like on the opposite side of the editor-author relationship? Has your time at the CR and Acre Books changed the way you think about the editing process as an author, particularly throughout the submission, editing, and production stages of Romances?

LA: Though I’d been a literary magazine editor before that first book and chapbook, I didn’t know as much about the book-publishing industry then. I did know that most editors I encountered as an author were working hard, so I tried to emphasize that when I needed things, I was patient about when they’d be available/finished.

Working at the CR and Acre gave me more insights into copyediting and production, so before I sent the final manuscript for Romances to LSU Press, I acted like it was a text that came across my desk for copyediting, and I found some errors (hyphenation, for example) I’d missed during the writing stages. I tried to be receptive and timely in my responses to their able edits, which helped me resee some lines/formatting/etc. I hadn’t thought about enough. And I knew when I needed to let the professionals do their jobs: I gave them some ideas about possible covers, but it wasn’t my place to do any more than that. Of course the LSU Press designer did a fabulous job with the cover!

JJM: As someone who has been on both sides of the editor-author relationship, what advice might you have for aspiring editors or authors? Is there a side you prefer to be on (either as an editor or author)?

LA: A lot of authors do end up as editors, or vice versa, because a love for literature and writing means you often feel a pull to both receive/read and transmit/write. I’m glad I get to do both, and each role feeds the other for me. When I read fabulous work for Acre, for example, I’m inspired to get back to my own desk. I would find it hard to choose one over the other.

I’d recommend that aspiring editors spend as much time reading as possible, find a way to be an apprentice to someone who knows what they’re doing, and be willing to try things that seem out of their wheelhouse at first.

For aspiring authors, I recommend separating the art and the process of creation from the business side of the industry as much as possible. Set aside different blocks of time for writing and for submitting work or otherwise dealing with the correspondence endemic to our industry. Don’t let rejections slow you down (I admire those who strive for one hundred rejections in a year, because it means they’re constantly submitting and not, I hope, letting each individual reply discourage them in some way), but make sure that you’re sending your work to venues that are appropriate for it—and that you’re following the directions.

You can read more about Romances at LSU Press or on Lisa’s author site.