In our current issue, we feature a story by Siân Griffiths, “Wooden Spoons,” which describes a man watching his estranged daughter on a cooking competition. Today, to accompany the story, we offer you Griffiths’s “Scones: A Recipe,” just in time for baking for Saint Lucia’s Day or your next holiday party. Enjoy!

“Scones: A Recipe”

Your British father tells you that traditional scones are made with currant, and the recipes you look up one after another agree, but you’ll dismiss this idea because you’re American, and though tradition may have gotten you as far as scones, it didn’t get you as far as currants. Opt instead for lemon-ginger in honor of his mother, your Gran. Crystallized ginger was her favorite, and your mother bought it for her, dipped in dark chocolate, year after year after year on Christmas, which is tradition enough.

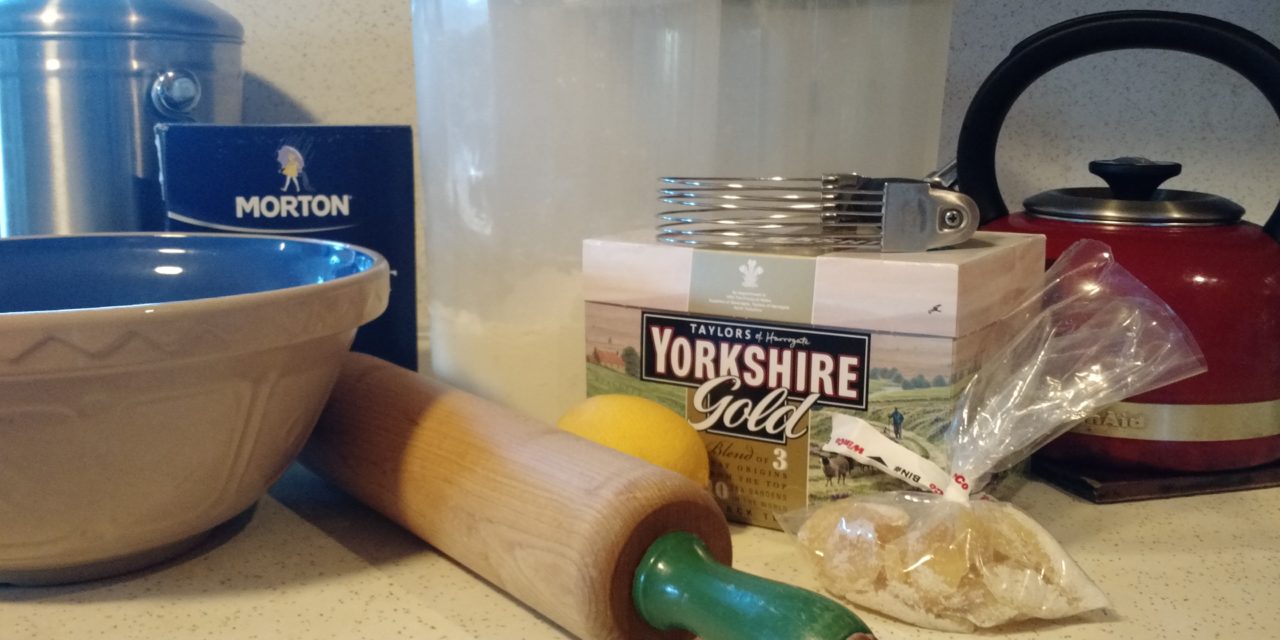

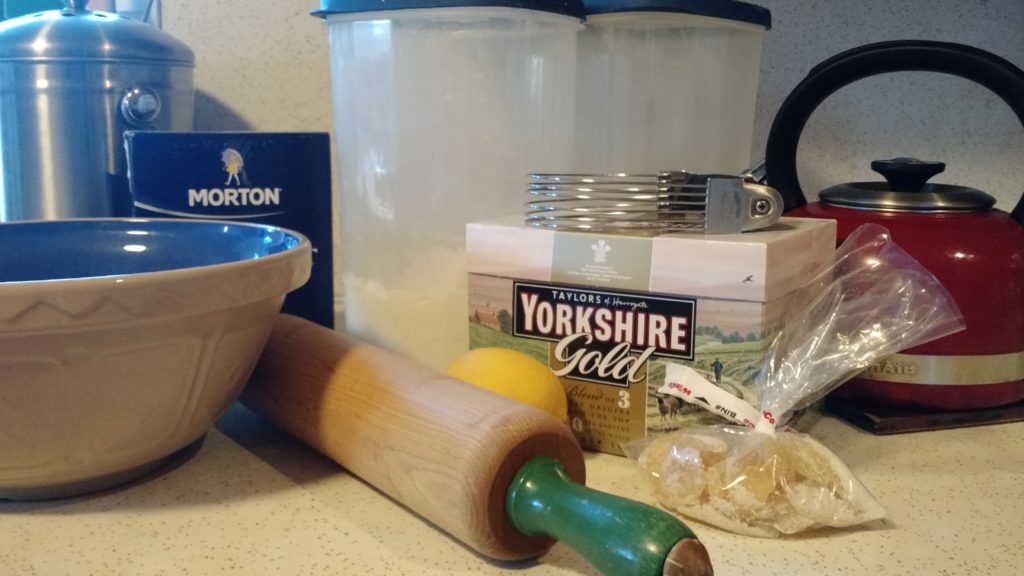

Dig in the back of the top shelf for the crystallized ginger. Decide how spicy you’re feeling. Six-pieces-level spicy? Seven? Chop ten pieces, pulling eight nice-sized chunks to the side for later.

In a bowl: 1 ¾ cups of flour, 3 tablespoons of sugar, 2 ½ teaspoons of baking powder, ½ teaspoon of salt. Salt is not optional. Stir with a whisk that’s probably too small for the job but is the only whisk you own, one you bought in a grocery store years ago. Tell your son that it won’t be too much longer, even though you’ve only just begun.

Take a stick of butter and cut off two thirds. Put the remaining bit on the butter tray. Slice the two-third hunk lengthwise in four, then turn it on its axis and slice it lengthwise in four again. Slice the short side, letting the slices fall apart into neat sixteenths that make you feel like a math genius and cooking pro. Relish this. Should the scones fail, you’ll still have this victory.

At this point, every recipe will suggest you cut the butter in to keep it cold, but the butter always gets stuck in the pastry cutter and you have to pull it free with your fingers, which warms the fat anyway and is a pain in the butt and makes another dish. Forgo the cutter. Enjoy how cool the flour is on your fingers, how fine, how soft, as you press the butter in.

Let your mind wander as you sift and press the flour and butter in your fingertips. Remember the girl who told you that it doesn’t count as being the daughter of an immigrant if your immigrant father was only British. Remember the precision of your grandmother’s back garden with its perfect border of perfect flowers. Wonder why you even own that stupid pastry cutter.

Every scone recipe worth its salt will now suggest you chill the dough for an hour, but the clock is ticking toward ten, and these are supposed to be breakfast. Your son is circling the kitchen like a shark sniffing for prey. Skip this step.

Retrieve the flour-silted whisk and a glass measuring cup. In it, beat an egg with maybe a 1/3 of a cup of the last bit of half-and-half your husband had bought for his coffee.

Zest a lemon into the flour and toss it with a fork. Pour in the eggy half-and-half, adding milk from the carton if it looks too dry. Pour a glass for your son while you’re at it. Tell him Nearly.

Add the ginger when everything is almost coming together. Check to make sure your oven is on. It isn’t. Turn it to 400°.

Roll the dough with the rolling pin you found at an old Idaho farmer’s estate sale, its wood still rich and oiled with butter from a hundred pies and biscuits made by a woman you never knew. You want it thick and not too pretty. Make it round. Round-ish. Nearly round-ish with rough sides patted in. Call these lacey. Roughness as decor, the personal touch.

Juice the lemon into the quick-rinsed measuring cup. Brush the juice over the dough. Sprinkle liberally with raw sugar. Cut the dough in half and in half and in half and in half. Press one reserved ginger chunk into the middle of each of the eight pieces.

Bake ten minutes, twelve—until the edges toast. Wash the dishes while they bake. Remember your British aunt, a caterer, how quick she was with the washing up. Think of her frantic scrubbing and the way it shook her perfectly coiffed hair free, if only temporarily. Remember how her skirts only loosely matched her thin sweaters, a British version of matching. Remember how even her slippers had heels. You inherited none of her formality. In fact, you can’t think of a single trait you share except perhaps the ability to get every dish cleaned, dried, and put away before the timer beeps.

Set the scones on a rack. Your family is with you now, the living and the dead, summoned by the scent. Notice the remaining half a pot of coffee, still hot on the warmer. Make a cup of tea instead, Yorkshire Gold, with sugar and milk. The scones are hot, crisp on the surface but soft and steaming inside. Their butter fat feeds something deep. Sip your tea. You were born in Ohio and raised in the West, but this morning, remember you’re only American-ish.